Read Coronation Everest Online

Authors: Jan Morris

Coronation Everest (8 page)

Soon I would be following them, for I planned to make an early ascent of the icefall; but first I wanted to acquire some more general impression of the shape of the mountain. On the other side of the valley rose Pumori, heavily snow-capped. The lower part of its mass was of bare rock, with the scree of the moraine leading up to it, and it would be easy enough to reach a convenient ledge upon its flank and look across to the mass of Everest. Accordingly Sonam and I set out in the early morning to cross the glacier and climb it. It was a tiring job, for I was still unacclimatized, and the ridge I had chosen as our objective was at about 20,000 feet. The moraine was a

bore, for it ran in high ridges intersected by slippery shaly gulches; it took a great deal of effort to cross it and begin the upward climb. By the time we were approaching the ridge, towards midday, I was so breathless that I staggered from boulder to boulder helplessly, bending over each big rock to pant my breath back; but at last we sat there, Sonam and I, and leant back to enjoy the view. We had brought some biscuits and jam with us; and from time to time, spreading a biscuit thickly with the confection, we would reach out a hand for a lump of snow, press it into a convenient block, and enjoy a sort of sickly ice-cream sandwich.

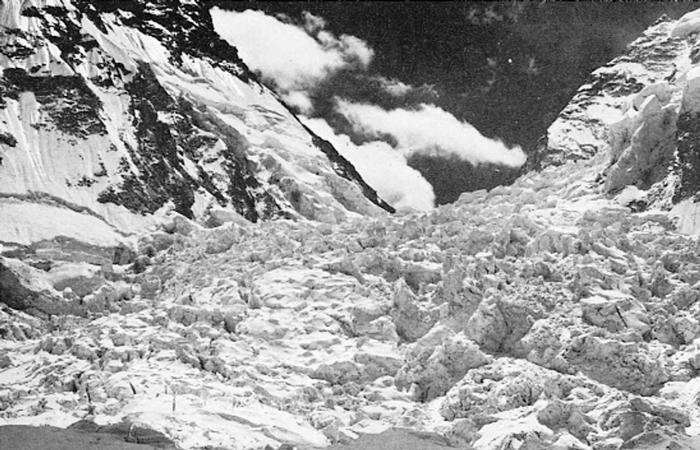

There it stood, this monstrous mountain; for the first time I could see it as a whole. It seemed to glower at me. Mallory said it was like a prodigious fang excrescent from the jaw of the earth; so sulky and brooding did it look that morning that I thought it must have a toothache. Great mountains surrounded it on every side, but it looked recognizably the greatest (and nastiest) of them all. The rock slabs of its upper slopes were almost free of snow, and only the thinnest plume was driving from its summit; it had a very cold and calculating look about it, as if it were working out the dentist’s bill. We could see almost all the route first followed by the Swiss, and now to be retraced (with minor variations) by the British. First came the awful shattered wilderness of the icefall, a mass of broken, tumbled, tilting, shifting, tottering blocks of ice, intersected by innumerable crevasses, swept by avalanches from the rock walls on either side of it. It looked like a huge indigestible squashed meringue. Beyond it was the valley of the Western Cwm, a cleft cut in the side of the mountain, narrow and overhung, and sunk in an unearthly white silence. The steep mountain

wall of Lhotse bounded it, rising as a precipice to the flat plateau of the South Col, at 26,000 feet or more. There the climbers would turn to the north, and make their perilous way up the long final ridge of the mountain. A small bump not far from the top was called the South Summit; after that a precipitous rock ridge led to the summit proper. We could see it all, from the minute tents of Base Camp, far below us, through the successive obstacles of the mountain, to the little empty dome of rock that was the target.

We could see more; for while the southern side was bathed in sunshine, expectantly, to the north we could see the Tibetan approaches to Everest, suggestively shadowy. This was the route of the old Everesters, from the glacier of Rongbuk to the North Col, and along wearing snow slopes towards the summit. There were all the landmarks of those old adventures – the first and second steps, the yellow band, North Peak – names familiar to whole generations of climbers and mountain-lovers. An invisible barrier of politics and prejudice shielded those places from us; all the same (it may have been the altitude, or the heat of the sun, or the cold of the snow) I fancied there were spirits watching us still, over the gateway of the Lho La.

We scrambled down the mountain-side again in the heat of the afternoon, scraping our shins on innumerable rocks, and sometimes slithering uncontrollably down the scree. It was an exhilarating descent. Near the level of the valley floor we suddenly found ourselves standing on the edge of a small tarn, for all the world like some isolated Welsh mountain lake, its water green and unruffled. There was no trace of ice upon its surface, and it stood there demurely, tucked away behind the moraine. Weeks later

Tenzing noticed this little lake from high on Everest, and in 1954 members of an Indian expedition trying to climb Pumori set foot upon its banks. They claimed to be the first people ever to reach it, and gave it an Indian name. They were not. Sonam and I were the first, and its name is Lake Elizabeth.

Down we went, and when next I looked up from the tricky terrain there was the bulk of Everest looming above us. Its summit was hidden by the projecting North Peak, and I could see only the top of Lhotse above the vast frozen morass of the icefall. It looked as if you could lose an army in its secluded corners. For a moment, on my ridge of Pumori, it had occurred to me that if I stood up there on the day of assault, I might see the tiny figures of the victorious climbers high upon the very summit. Now I pondered again upon the gigantic scale of it all, and realized that if ever a pair of climbers reached the top of Everest, only the gods (and those watchful spirits of the Lho La) would be able to see them there.

Towards the end of April I made my first journey on to Everest. The runners were performing smoothly, leaving at regular intervals with my dispatches, and generally doing the journey to Katmandu in eight or nine days. Between us, Hunt and I had described in detail the march out to the mountain, the period of acclimatization, the move up to Base Camp, the first reconnaissance of the icefall, the establishment of a route through its shifting dangers. It was time, I thought, to see something of life higher on the mountain.

I left one fine morning after breakfast, with Band and Westmacott, and followed them across the crisp brittle ice-lane that led us, wandering through the moraine, to the foot of the icefall. There we roped up – three sahibs, four or five Sherpas. This was my introduction to mountaineering, and clumsy indeed were my movements as we moved off. If ever a rope could tangle, it was mine. If ever a pair of crampons would not fit, they were those kindly issued to me by the expedition. My snow-goggles were nearly always steamed up, making it extremely difficult to see anything at all. My boot-laces were often undone, and trailed behind me forlornly. Nevertheless, buckling my rucksack around me, and taking a determined grip upon my ice-axe, I followed the large flat expanse of Band’s back into the wilderness.

It would be foolish to say that I enjoyed this first climbing of the icefall, especially as I was still ill-acclimatized; but there was a grave fascination to our progress up so jumbled and empty a place. The icefall of Everest rises two thousand feet or more and is about two miles long. It is an indescribable mess of confused ice-blocks, some as big as houses, some fantastically fashioned, like minarets, obelisks, or the stone figures on Easter Island. For most of the time you can see nothing around you but ice; ice standing upright, as if it will be there for eternity; ice toppling drunkenly sideways, giving every sign of incipient collapse; ice already fallen, and lying shattered in sparkling heaps; ice with crevasses in it, deep pale-blue gulfs, like the insides of whales; ice to walk over, pressed and piled in shapeless masses, in alleys and corridors and cavities; like some vast attic of ice, at the top of a frozen house, full of the cold icy junk of generations. All this mass was slowly moving, so that it creaked and cracked, and changed its form every day; and from the high mountain walls on either side, squeezing the icefall together like the nozzle of a toothpaste tube, avalanches came tumbling down.

Much of the climbing of the icefall consisted of a precarious trudging through this frozen morass; for the new-comer a breathless process, relieved only by hastily snatched moments of rest upon the head of his ice-axe. Now and again, as we climbed, we could see through gaps in the ice-mass into the valley below, with Pumori growing small behind us, and Base Camp out of sight over the lip of the ice. Soon we were on a level with the Lho La, and could see over it into the mysteries of Tibet; they looked to me very like the mysteries of Nepal. On either side of us, as the icefall narrowed, loomed the rock walls of Everest and Nuptse, so that one felt hemmed in and vaguely

threatened. Sometimes we stopped for a rest and a draught of lemonade from Band’s bottle; but most of the time we trudged.

It was a dangerous place, the icefall, chiefly because of its incessant movement. Our route was roughly marked by small red flags stuck in the snow or in the flanks of the ice-blocks; but here and there, deep in dangerous gullies, or high on inaccessible pinnacles, other flags were flying, tilting crookedly, sad and tattered. These odd souvenirs had marked the Swiss route in 1952, and it was poignant to see them now, so far from a safe way, like little red Sirens in the ice – not least because they had been provided by a munificent shoe manufacturer, and still proclaimed the name of his product in what seemed rather a forlorn kind of advertising campaign.

Sometimes our route lay up the steep side of an ice-block, and there the Sherpas, with their heavy packs, would swing wildly up a fixed rope, groping and scraping

and clasping hand-holes, until they were heaved up by their comrades at the top and shook the snow off themselves as a dog shakes off water. Sometimes we squeezed through minute cracks in the ice, our packs catching and sticking, until we pushed our bodies through with an almost perceptible ‘pop’. In one place we had to manoeuvre ourselves through such a gap, slither down a confined ice-slope, jump across a crevasse, and climb up the other side. I floundered my way down this place, poised for a few agonizing moments across the crevasse, wondering which leg to move next, and somehow scrambled up the other side; but during this process I felt my wrist scraping hard along an ice-block, and when next I wanted to find out the time, I discovered that my watch had gone, down into the depths of the crevasse. It was an automatic watch, wound up by the motion of my wrist; and I believe that it is still ticking away there in the blue vaults of the glacier, rocked and stimulated by the movements of the ice, inching its slow way down into the valley, still faithfully recording Greenwich mean time.

Often such crevasses were too wide to jump, and had to be bridged. The expedition had a few sections of aluminium ladder for this purpose, across which one picked one’s way like a big spider. But there were many more crevasses than there were ladders, and most of them were bridged by another device: a greasy old pole, jammed into the snow on either side, like a huge toothpick jammed between molars. I found these poles unsympathetic. Each climber had to cross alone, his companions hanging on to the rope at either end; and the spikes of my crampons, which were generally loose anyway, used to stick into the wood in a disconcerting way. As often as not the pole would start rotating greasily in the snow as you picked

your way across, and it was difficult to know whether to watch it rolling, or to let your eyes slide off into the great hungry depths of the crevasse below you, a hundred feet deep or more, cold and blue.

As the evening approached it began to snow, as it often did on Everest. In the sunshine the icefall could be a stifling place, for the heat was caught between the walls and pillars of ice, and was able (so few were the available targets) to pick you out personally for a roast. There was a particular malevolence about this heat, as if it were in league with all the other menaces of the place – the shifting blocks, the gaping holes, the greasy poles, the dazzle, the dulling altitude, the avalanches – and even the lovely blue sky and the sunshine seemed unfriendly. So I always welcomed the first soft wisps of snow in the late afternoon. They drifted idly at first, out of a blue sky; but gradually the day turned grey, the clouds thickened, and the great mountain masses were obscured. On went our wind-proofs, and through the rising snow we laboured, the moisture trickling down the backs of our necks; if we looked to the south, down the valley of the glacier, we could see battalions of wet clouds marching up towards us, far below.

Half-way up the icefall a small staging camp, Camp II, had been placed on a plateau jutting over the morass. This we reached comfortably just as the snow began to be unpleasant. I remember my first night at this camp with especial clarity. The mountain had seemed lifeless and impersonal till now, like a great slab of grumpiness; but the presence of this imperturbable little camp, perched there among the ice, suddenly gave the place a spark of life, and humanized the adventure.

***

There was a cheeky Cockney flavour, I thought, about the very existence of the place; and in the face of so gigantic and uncompromising an overseer as Everest, there was a new attraction in impertinence. I used to like to lie in my tent in such a camp as this watching a team of sahibs and Sherpas come toiling up the monster to the plateau. Over the ridge they would come, their tired bodies bent, with a little extra springiness entering their steps as they saw the tents ahead of them. Wearily they plunge their ice-axes into the snow, unfasten the rope with their stiff cold fingers, and untie (with many a hissed or muttered scurrility) the frozen straps of their crampons. The Sherpas hustle off to some of the tents; the Europeans, seeing that the supplies are stacked properly, into others. Then what a heaving, heavy blowing, bulging, rolling and twisting ensues! Each tent is no more than three feet high, and it has a narrow sleeve entrance near the ground; into this small hole the tired climber must struggle, wearing awkward windproofs or thick down clothing. There is a maddening struggle with the flapping sleeve of the tent (the snow dripping, all the while, or blowing past in chilling gusts); boots get caught up with nylon tentage; rucksacks have to be dragged in behind, like stubborn fat terriers on leads.

Inside the tent is probably a little clammy, for it has been empty since the last party went this way. Litter lies about its floor – a bar of chocolate, a packet of breakfast food, a scrap of old newspaper. There is a smell of lemonade powder, wet leather and chocolate. In one corner is a walkie-talkie set, a tangle of wires and batteries. Once inside this uninviting place, the climber twists himself about laboriously and slowly removes his boots, banging them together to clear them of clinging snow (I always remember the sound of banged boots, most redolent of Everest). He heaves his

inflatable mattress from his rucksack, the tent bellying around him, and blows it up in a series of impatient gasps. He stretches it on the floor – it just fits in – and places his sleeping-bag on top of it. A few more contortions inside the tent, like a ferret down a rabbit hole, and into this bag, socks, down clothing, gloves and all, the climber gratefully if ungracefully crawls. He uses his boots as a pillow; if he leaves them loose in the tent they will certainly be frozen hard in the morning, and trying to unfreeze a pair of climbing boots is a frustrating task. If he is far-sighted he has packed a book in his rucksack, for it may only be three or four o’clock, and the hours pass slowly. (The expedition carried a wide variety of literature. Wilfrid Noyce used to sit in the snow romping through

The Brothers Karamazov

. The two New Zealanders used to enjoy the ineffable respectability of the

Auckland Weekly News

. The official library ranged from

Teach Yourself Nepali

to Orwell’s critical essays, with, oddly enough, not a single mountaineering book borrowed from the warped deal bookshelves of the Climbers’ Club Hut at Helyg. I had a proof copy of W. H. Murray’s

Story of Everest

, though, which we all read at one time or another on the mountain; everybody signed it for me, and it now stands in my library clad in a resplendent binding, its pages marked with the tea-stains and fingerprints of Everest.)

Before long the climber will be disturbed by a flurry and a commotion at the entrance to the tent, and a grinning Sherpa, puffing heavily in the cold, pushes in some food – pemmican, potatoes, a tin plate of mashed sausage meat. Sweet thick tea follows, tasting faintly of methylated spirits and strongly of the melted snow which provided the water – a taste, I used to think, desperately compounded of winds and desolation, for a raindrop frozen on the slopes of

Everest must be a lonely sort of thing. There may be biscuits and jam, packed in transparent packets like shampoo, or perhaps round slices of fruit cake, from a tin. It is not easy to eat delicately in a high-altitude tent. Sooner or later a mug will overturn, and a thin trickle of brown tea will settle into a puddle on the floor; crumbs innumerable crawl inside the sleeping-bag; where the blazes has that fork got to?

In the evening Hunt tries to link all the camps on the mountainside with a radio call over the walkie-talkie sets. This demands some preparation. Batteries work better when they are warm, so they must be cherished inside the sleeping-bag, like teddy-bears, for half an hour before the appointed time; they are angular things, covered with odd protrusions, sockets, holes and joints, and make uncomfortable bedmates. Then the tangle of wires in the corner must be sorted out, and the long flexible aerial, like a stage property sword, fitted into the receiver. At a pinch a determined man can do it all inside his tent, without once poking his nose outside, and Hunt’s intricate instructions on the next day’s duties can be absorbed in the warmth.