Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court (26 page)

Read Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #England, #History, #Royalty

John Hervey was likewise uninterested in his children, and his passion for politics also separated him from Molly. Sir Robert Walpole, Hervey’s great friend and ally, ‘had formerly made love to her, but unsuccessfully … Sir Robert Walpole, therefore, detested Lady Hervey, and Lady Hervey him.’

58

In writing about this incident, John Hervey, a man of his time, seems to have valued the political bond that he shared with Walpole more highly than the relationship he’d once had with his wife.

As Caroline’s strongest supporter, Hervey always made a point of running down Henrietta. Although Caroline ‘affected to approve’ of her husband’s ‘amours’, she was in fact rather jealous of whatever vestige of influence Henrietta may have had.

So she made quite sure that the door to Henrietta’s apartment ‘should not lead to power and favour’, and that the hopeful sycophants who traipsed through it should leave disappointed.

59

John Gay, for one, found that his friendship with Henrietta was worthless, and ‘the queen’s jealousy’ prevented his ever being offered an important job at court.

60

Lord Chesterfield, too, fell from favour for the same reason: he was detected paying a night-time visit to Henrietta, ostensibly to deposit with her for safe-keeping a large sum of money won by gambling. Caroline discovered his perfidy, and Chesterfield paid the price of her displeasure.

61

While Henrietta shrank away from political intrigue, Caroline clearly relished it. She and Sir Robert Walpole had a system of secret code words to use when the king was present, so that they could together change tack in conversation in a manner ‘imperceptible by the bystanders’.

62

George II was blithely unsuspicious of the fact that he was being manipulated, and would sometimes ‘cry out, with colour flushing into his cheeks’ that Sir Robert was ‘a brave fellow’ who had ‘more spirit than any man [he] ever knew’.

63

As the satirists had it, Caroline was all-powerful:

You may strut, dapper George, but ’twill all be in vain;

We know ’tis Queen Caroline, not you, that reign …

Then if you would have us fall down and adore you,

Lock up your fat spouse, as your dad did before you.

64

Yet the cunning Walpole boasted that he, not she, ultimately pulled the strings of this puppet king:

Should I tell either the King or the Queen what I propose to bring them to six months hence, I could never succeed. Step by step I can carry them … but if I ever show them at a distance to what end that road leads, they stop short, and all my designs are always defeated.

65

*

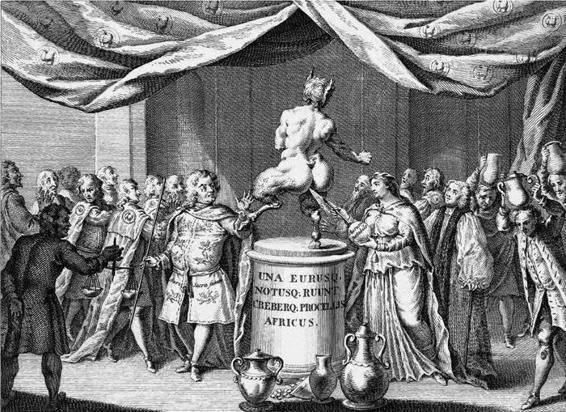

A satirical print called

The Festival of the Golden Rump

. Queen Caroline injects magic medicine up a raving, satyr-like George II’s backside in order to bring him back under her control. Sir Robert Walpole looks on approvingly; the courtiers are shown as bizarre savages taking part in an exotic ritual

When George II and Caroline first became king and queen, Henrietta had lived for several weeks in real fear of being kidnapped by her violent husband. Charles Howard had hoped for some time to win financial advantage for himself by threatening to demand the return of his wife. He had even obtained a warrant from the Lord Chief Justice giving him the authority to seize her by force. But Henrietta ‘feared nothing so much as falling again into his hands’, and consequently ‘did not dare to stir’ outside St James’s Palace.

The stout Caroline proved herself on this occasion to be a doughty protector to Henrietta. When Charles Howard actually attempted to storm the queen’s apartment, in search of his wife, Caroline boldly stood her ground. Afterwards she admitted that she’d been ‘horribly afraid’, knowing him to be ‘brutal as well as a little mad, and seldom quite sober’. She thought him quite capable of throwing her out of the window.

66

Once Howard had been ejected from the palace, the whole matter was hushed up. He was given money to leave the king’s mistress alone, ‘and so this affair ended’, the king reluctantly paying

£

1,200 in order to retain the lover he no longer desired, and Howard receiving the bribe ‘for relinquishing what he would have been sorry to keep’.

67

‘Marriage is traffick throughout’, claims a character in one of Henry Fielding’s contemporary dramas, expressing views shared by Charles Howard. ‘As most of us bargain to be husbands, so some of us bargain to be cuckolds.’

68

Molly Hervey understood perfectly how Henrietta’s fear of her husband compelled her to remain in her degrading relationship with the king, and commiserated with her about the long-drawn-out fading of George II’s favour: ‘the sun has not darted one beam on you a great while. You may freeze in the dog-days, for all the warmth you will find from our

Sol

.’

69

Indeed, Henrietta became increasingly anxious to retire from the court, despite the protection that it offered against her husband. ‘How soon it will be agreeable to you that I leave your family?’ she asked George II in one undated letter, making an attempt to retreat from royal service. ‘From your Majesty’s behaviour to me, it is impossible not to think my removal from your presence must be most agreeable to your inclinations.’

70

But this storm, like many others, blew over, and Henrietta was obliged to stay.

In 1728, she finally succeeded in persuading her husband to sign a formal deed of separation, an extreme and very rare proceeding for her age and social class.

71

It was wonderful to be able to cut loose from him at last, but freedom came at a high price.

She had no chance of winning custody of her only child, and it seemed unlikely that she would ever see her beloved son again.

*

Kensington Palace was the backdrop to the world in which Henrietta had to live but longed to leave. Her apartment there was ‘very damp and unwholesome’, situated in a semi-basement

three feet underground. Insanitary and unhealthy, its floor produced ‘a constant crop of mushrooms’.

72

The south view of Kensington Palace, with courtiers gliding about the lawns

Surprisingly, the Georgian kings verged upon the miserly in the facilities they provided for their households. George II prided himself upon at least attempting to live within his means and shunned superfluous expenditure on palaces and parties. This was partly because the nature of monarchy itself was changing. People were beginning to query the need for the extravagant baroque architecture now to be seen across Europe, and to question the authority of the absolutist kings who commissioned it. According to William Hooper, writing in 1770, ‘the glory of a British monarch consists, not in a handful of tinsel courtiers’, but in the ‘freedom, the dignity and happiness of his people’.

73

Henrietta and her colleagues paid for this attitude with slightly substandard accommodation.

Yet the palace in the park provided a snug refuge from life in London, where Henrietta would have found it hard to live in the civilised style to which she had grown accustomed. The previous year, a visitor to grimy London found it deeply disappointing, ‘many of its streets being dirty and ill-paved, its houses of brick, not very high … blacken’d with the unmerciful smoke of coal-

fires’.

74

Henrietta’s court salary,

£

300 a year, would have been just enough to afford ‘a pint of port at night, two servants, and an old maid, a little garden … provided you live in the country’.

75

Her pension, were she to leave court, would not support a London life of any pretension whatsoever.

Visitors to Kensington Palace drove from town across Hyde Park. At intervals along the way, posts were enchantingly topped with lighted lanterns ‘every evening when the Court is at Kensington’. The enduring name of this road through the park, ‘Rotten Row’, is probably a corruption of the ‘

Rue du Roi

’, or ‘King’s Road’, originally built for William III but improved for the Georgian monarchs.

The gardens surrounding Kensington Palace were now beginning to take on their final form, which remains recognisable today. A visitor in 1726 had found no fewer than fifty labourers hard at work making improvements to the palace’s immediate surroundings.

76

The royal gardener, Charles Bridgeman, had been busy ‘planting espaliers and sowing wood’ all around the building, and the vast Round Pond was dug to provide a pleasing prospect from the drawing room’s windows.

77

The glades and avenues of the ‘delightful’ and ‘glorious’ Kensington Gardens were opened to the public on Saturdays, ‘when the company appeared in full dress’.

78

Here Caroline indulged her almost superhuman love of walking. She often exhausted her ladies-in-waiting (one of them ‘was ready to drop down she was so weary’ after a royal ramble), but the devoted Peter Wentworth loved a ‘good long limping walk’ with his queen.

79

Sometimes he and she walked together ‘till candle-light, being entertain’d with very fine french horns’.

80

It’s understandable that Caroline loved gardens, where a little more freedom of movement and conversation might be possible than indoors. As John Hervey asked, ‘is the air sweeter for a court; or the walks pleasanter for being bounded with sentinels?’

81

This was truly the heyday of the palace proper at Kensington, with its water system, transport, cleaning and cooking arrangements

by now well established and finely tuned. During the reign of George I, Kensington’s state apartments had been used ‘only on publick days’ and otherwise left locked.

82

In the summer of 1734, though, the whole palace was buzzing with life and activity. ‘My time at Kensington’, wrote Peter Wentworth to his brother about his new life in Caroline’s service, ‘was very precious.’

83

Wentworth also described the daily court routine: ‘up every morning by six a clock and ride out by 8 or 9 till 11; then new dress for the

levées

, and morning drawing room’. Then, he said, ‘we go to dinner at three and start from table a little after 5 in order to walk with the Queen’. At six, everyone returned and sat down to cards in the drawing room. Wentworth had recently been appointed to the paid position of managing the public lottery, and had begun to dare to hope again that his sober and assiduous attendance at court would result in a further promotion of some kind: ‘if I don’t make something of it at last I shall have hard fate’.

84

In 1734, Mrs Jane Keen, now well settled into the job of palace housekeeper, made a survey of all the chimneys that needed sweeping, and her list gives a good idea of how the accommodation was laid out. All in all there were 246 chimneys in the palace, requiring a sweep ‘every 14 or 21 days’ when the court was in residence and the fireplaces ‘in constant use’.

85

Mrs Keen began her tour of the palace at the ‘porter’s lodge’ (one chimney), then moved on to the ‘Stone Gallery’ range, which was packed with courtiers’ lodgings, including those of John Hervey (one chimney). There too was the apartment reserved for the ‘Lord of the Bedchamber’ in waiting at any particular moment (three chimneys).