Crazy Salad and Scribble Scribble

Read Crazy Salad and Scribble Scribble Online

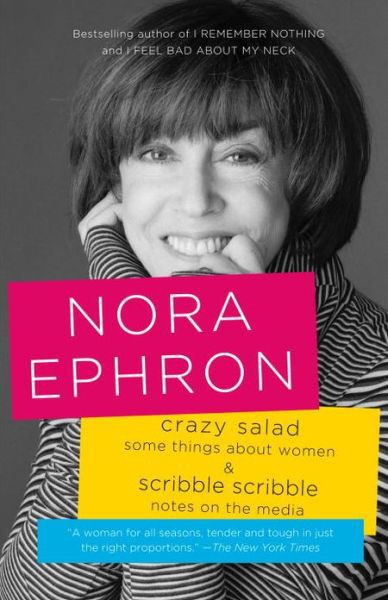

Authors: Nora Ephron

Tags: #Biographical, #Essays, #Nonfiction, #Retail

Nora Ephron

“Nora Ephron can write about anything better than anybody else can write about anything.”

—The New York Times

“Stylish, opinionated, with a kind of take-no-prisoners fearlessness rooted in both the women’s movement and the equally complex terrain of her own emotions.”

—

Los Angeles Times

“As tart and refreshing as the first gin and tonic of summer.”

—

The New York Times Book Review

“A brilliant, restless mind.”

—

Ms

.

“Funny, shrewd, devastating.”

—

Newsweek

“Nora Ephron is, in essence, one of the original bloggers—and if everyone could write like her, what a lovely place the Internet would be.… Telling stories that were, more often than not, ultimately about herself, and doing so with such warmth, wit and skill that they became universal.”

—The Seattle Times

“Always funny.”

—Mademoiselle

“Pure delight.”

—

Playboy

Crazy Salad & Scribble Scribble

Nora Ephron is also the author of the bestsellers

I Feel Bad About My Neck

,

I Remember Nothing

, and

Heartburn

. She received Academy Award nominations for Best Original Screenplay for

When Harry Met Sally …

,

Silkwood

, and

Sleepless in Seattle

, which she also directed. Her other credits include the plays

Imaginary Friends

and

Love, Loss, and What I Wore

, and the films

You’ve Got Mail

and

Julie & Julia

, both of which she wrote and directed. She died in 2012.

FICTION

Heartburn

ESSAYS

I Remember Nothing

I Feel Bad About My Neck

Nora Ephron Collected

Scribble Scribble

Crazy Salad

Wallflower at the Orgy

DRAMA

Love, Loss, and What I Wore

(with Delia Ephron)

Imaginary Friends

SCREENPLAYS

Julie & Julia

Bewitched

(with Delia Ephron)

Hanging Up

(with Delia Ephron)

You’ve Got Mail

(with Delia Ephron)

Michael

(with Jim Quinlan, Pete

Dexter, and Delia Ephron)

Mixed Nuts

(with Delia Ephron)

Sleepless in Seattle

(with David S.

Ward and Jeff Arch)

This Is My Life

(with Delia Ephron)

My Blue Heaven

When Harry Met Sally …

Cookie

(with Alice Arlen)

Heartburn

Silkwood

(with Alice Arlen)

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, OCTOBER 2012

Crazy Salad

copyright © 1972, 1973, 1974, 1975 by Nora Ephron

Scribble Scribble

copyright © 1975, 1976, 1977

,

1978 by Nora Ephron

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Crazy Salad

was originally published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1975.

Scribble Scribble

was originally published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1978.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Portions of

Crazy Salad

have appeared in

Esquire

magazine,

New York

magazine, and

Rolling Stone

.

The articles in

Scribble Scribble

have been previously published in

Esquire

magazine, except “Gentleman’s Agreement” which appeared in MORE magazine.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Viking Press, Inc., for permission to reprint ten lines of poetry from

The Portable Dorothy Parker

. Copyright © 1926, renewed 1954 by Dorothy Parker.

The stories in

Scribble Scribble

have been previously published in

Esquire

magazine.

The Cataloging-in-Publication data is available at the Library of Congress.

eISBN: 978-0-345-80473-0

Cover design: Abby Weintraub

Author photograph © Elena Seibert

v3.1

For my sisters:

Delia, Hallie, and Amy

It’s certain that fine women eat

A crazy salad with their meat

—WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS

On Never Having Been a Prom Queen

Bernice Gera, First Lady Umpire

Women in Israel: The Myth of Liberation

Crazy Salad

I began writing a column about women in

Esquire

magazine in 1972. The column was my idea, and I wanted to do it for a couple of specific, self-indulgent reasons and one general reason. Self-indulgent specifics first: I needed an excuse to go to my tenth reunion at Wellesley College, and I was looking for someone to pay my way to the Pillsbury Bake-Off. Beyond that, and in general, it seemed clear that American women were going through some changes; I wanted to write about them and about myself. When I began the column, the women’s movement was in a period of great activity, growth, and anger; it is now in a period of consolidation. The same is true for me, and it has something to do with why it has become more and more difficult for me to write about women. Also, I’m afraid, I have run out of things to say.

There are twenty-five articles in this book that glance off and onto the subject of women, and as I go through them, I can think of dozens of others I could have done instead. I don’t deal with lesbianism here and, except peripherally, I don’t deal with motherhood. Month by month, I took what interested me most, and so I never wrote about a number of things that interested

me somewhat: panty hose, tampons, comediennes, the Equal Rights Amendment, Fascinating Womanhood, Bella Abzug,

The Story of O

, the integration of the Little League—I could go on and on. The point here is simply to say that this book is not intended to be any sort of definitive history of women in the early 1970s; it’s just some things I wanted to write about.

I have to begin with a few words about androgyny. In grammar school, in the fifth and sixth grades, we were all tyrannized by a rigid set of rules that supposedly determined whether we were boys or girls. The episode in

Huckleberry Finn

where Huck is disguised as a girl and gives himself away by the way he threads a needle and catches a ball—that kind of thing. We learned that the way you sat, crossed your legs, held a cigarette, and looked at your nails—the way you did these things instinctively was absolute proof of your sex. Now obviously most children did not take this literally, but I did. I thought that just one slip, just one incorrect cross of my legs or flick of an imaginary cigarette ash would turn me from whatever I was into the other thing; that would be all it took, really. Even though I was outwardly a girl and had many of the trappings generally associated with girldom—a girl’s name, for example, and dresses, my own telephone, an autograph book—I spent the early years of my adolescence absolutely certain that I might at any point gum it up. I did not feel at all like a girl. I was boyish. I was athletic, ambitious, outspoken, competitive, noisy, rambunctious. I had scabs on my knees

and my socks slid into my loafers and I could throw a football. I wanted desperately not to be that way, not to be a mixture of both things, but instead just one, a girl, a definite indisputable girl. As soft and as pink as a nursery. And nothing would do that for me, I felt, but breasts.

I was about six months younger than everyone else in my class, and so for about six months after it began, for six months after my friends had begun to develop (that was the word we used, develop), I was not particularly worried. I would sit in the bathtub and look down at my breasts and know that any day now, any second now, they would start growing like everyone else’s. They didn’t. “I want to buy a bra,” I said to my mother one night. “What for?” she said. My mother was really hateful about bras, and by the time my third sister had gotten to the point where she was ready to want one, my mother had worked the whole business into a comedy routine. “Why not use a Band-Aid instead?” she would say. It was a source of great pride to my mother that she had never even had to wear a brassiere until she had her fourth child, and then only because her gynecologist made her. It was incomprehensible to me that anyone could ever be proud of something like that. It was the 1950s, for God’s sake. Jane Russell. Cashmere sweaters. Couldn’t my mother see that? “

I am too old to wear an undershirt

.” Screaming. Weeping. Shouting. “Then don’t wear an undershirt,” said my mother. “But I want to buy a bra.” “What for?”

I suppose that for most girls, breasts, brassieres, that entire thing, has more trauma, more to do with the coming of adolescence, with becoming a woman, than anything else. Certainly more than getting your

period, although that, too, was traumatic, symbolic. But you could see breasts; they were there; they were visible. Whereas a girl could claim to have her period for months before she actually got it and nobody would ever know the difference. Which is exactly what I did. All you had to do was make a great fuss over having enough nickels for the Kotex machine and walk around clutching your stomach and moaning for three to five days a month about The Curse and you could convince anybody. There is a school of thought somewhere in the women’s lib/women’s mag/gynecology establishment that claims that menstrual cramps are purely psychological, and I lean toward it. Not that I didn’t have them finally. Agonizing cramps, heating-pad cramps, go-down-to-the-school-nurse-and-lie-on-the-cot cramps. But, unlike any pain I had ever suffered, I adored the pain of cramps, welcomed it, wallowed in it, bragged about it. “I can’t go. I have cramps.” “I can’t do that. I have cramps.” And most of all, gigglingly, blushingly: “I can’t swim. I have cramps.” Nobody ever used the hard-core word. Menstruation. God, what an awful word. Never that. “I have cramps.”

The morning I first got my period, I went into my mother’s bedroom to tell her. And my mother, my utterly-hateful-about-bras mother, burst into tears. It was really a lovely moment, and I remember it so clearly not just because it was one of the two times I ever saw my mother cry on my account (the other was when I was caught being a six-year-old kleptomaniac), but also because the incident did not mean to me what it meant to her. Her little girl, her firstborn, had finally become a woman. That was what she was crying about. My reaction to the event, however, was that I might well be a

woman in some scientific, textbook sense (and could at least stop faking every month and stop wasting all those nickels). But in another sense—in a visible sense—I was as androgynous and as liable to tip over into boyhood as ever.

I started with a 28 AA bra. I don’t think they made them any smaller in those days, although I gather that now you can buy bras for five-year-olds that don’t have any cups whatsoever in them; trainer bras they are called. My first brassiere came from Robinson’s Department Store in Beverly Hills. I went there alone, shaking, positive they would look me over and smile and tell me to come back next year. An actual fitter took me into the dressing room and stood over me while I took off my blouse and tried the first one on. The little puffs stood out on my chest. “Lean over,” said the fitter. (To this day, I am not sure what fitters in bra departments do except to tell you to lean over.) I leaned over, with the fleeting hope that my breasts would miraculously fall out of my body and into the puffs. Nothing.