Crete (3 page)

Many hundreds of thousands of slow-dripping years have gone to form this crouching creature. He was already a very old bear when Artemis was brought from Asia to be incorporated in the pantheon of the Greeks. Not difficult to see why this cave would become the center of her cultâthe bear was sacred to her. But inside this same cave is another shrine, belonging to another faith: a chapel dedicated to Mary Arkoudiotissa and consecrated to the Purification of the Virgin. Mary inherited the bear, so to speak, just as the Orthodox Church inherited the ancient gods and absorbed them into its rituals.

Nikos Psilakis relates the local legend according to which the bear was alive once and used to come to the cave and drink up the water in the cistern, so that the monks of Gouvernetou went thirsty. They never caught the bear in the act of drinking, but when they went for water they always found the cistern dry. So one day they waited in hiding. But when the bear appeared it was so huge that they were panic-stricken. They couldn't see anything, the bear shut out the light. One of them began asking the Virgin to intercede. Even as he prayed, the bear, caught in the act of drinking, was turned to stone.

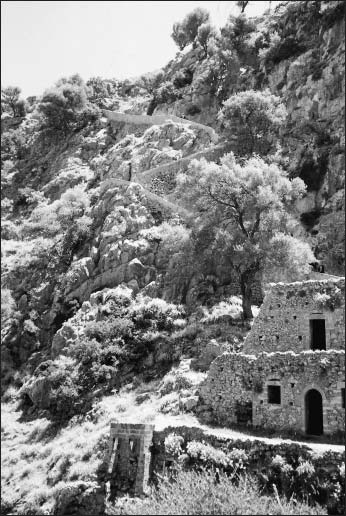

The path goes on descending, more steeply now, with steps cut in the rock. Half an hour or so brings you to the ruins of another monastery, this one with its own cave, and a deeply impressive oneâthe church itself is built into a cavern in the hillside. This is the Katholiko monastery, also known as the Monastery of St. John the Hermit, generally thought to be the oldest on Crete. It was abandoned by the monks three hundred years ago because of repeated pirate raids.

Whether, in its long history, Crete has endured more suffering through piracy than it has inflicted is a question that can have no final answer. The totals, on both sides, are beyond arithmetic. The Cretans practiced piracy even in prehistoric times. By Homer's day they were famous for it, raiding coasts far and near. The practice does not seem to have been frowned upon. In the fourteenth book of

The Odyssey,

Odysseus, passing himself off as a Cretan, relates his exploits as a pirate so as to gain the respect of his hosts, boasting of the nine raids that he made and the haul of plunder that fell into his hands.

However, in later times the island suffered terribly from Muslim corsairs raiding from their bases in North Africa. This was particularly so after 1204, when the Byzantine sea power was destroyed in the course of the Fourth Crusade and they were no longer able to patrol the coasts. Most of the best land lies on the coastal plains and so is peculiarly vulnerable. Oliver Rackham and Jennifer Moody, in their book on the making of the Cretan landscape, draw attention to the extreme fluctuations of population in these regions, which remained abandoned and uncultivated for long periods out of fear of pirate raids. The Venetians, during the centuries of their rule, maintained a fleet of galleys on the island whose main purpose was to protect the coasts against these marauders. But the situation did not greatly improve until the Turkish conquest in the seventeenth century, when the Christian islanders and the Muslim pirates became fellow subjects of the Ottoman Empire. This must be accounted one of the benefits brought about by Turkish occupationâthey were extremely few.

Katholiko is dramatic and spectacular in its desolation now, with its church cut into the rock, its monumental stone bridge spanning a deep chasm. Built to join the monastery buildings, the bridge joins only ruins now, arching proudly over a wilderness of rock and shrub. From the track above you can trace the course of the streambed, dry in the summer months, following the gorge to the sea, which is visible from here, a gleam of water, a narrow inlet, a stony beachâthe track of the pirates.

Remains of Katholiko monastery

The sides of this wild valley are dotted with caves, places of earlier worship perhapsâor earlier refuge. The cave of the hermit, in which he is said to have lived and died, lies just above the monastery, tunneling deep into the hillside, following the course of an underground stream. The saint's grave is here, but one needs a flashlight to see it. It is said that, enfeebled by his privations and ascetic way of life, he could no longer walk upright but stooped so much that it looked as if he was going on all fours. A man out hunting mistook him for an animal and wounded him fatally with an arrow. He was just able to crawl back to his cave, and there he died.

There is always a story, especially on Crete. It can sometimes seem that the whole island is a patchwork of stories, from primal myth to heroic legend to the embroideries of local gossip. But there have been some discoveries here that defy all attempts at narrative elaboration, so bizarre and surreal do they seem. The fossil bones of dwarf mammals have been found in Cretan caves, an elephant smaller than a bullock, a pig-size hippopotamus, a deer with legs shorter than a sheep's. The large mammals that were the ancestors of these beasts migrated to Crete some time after the end of the Miocene period, four million years ago, probably by following one of the land bridges that came and went, connecting Crete with adjacent mainlands. When these bridges were finally submerged, the migrants found themselves stranded on a mountainous island. They had no enemies to worry about, but the areas of standing water and marshland were steadily dwindling. They had to adapt or die. Smallness was the solution; without predators they didn't need to be so big and food supplies went further. By the time they encountered their first carnivores, in the shape of Neolithic man, they had forgotten how to run awayâ¦. After studying the bones, scientists have come to the conclusion that these dwarf hippos could climb. We are not far away here from the country of the centaur and the unicorn.

Returning to Chania on the western side of the peninsula via Stavros, one of the best beaches on the island, a slight detour brought us to the Venizelos graves, the stone-built tombs of Eleutherios Venizelos and his son Sophocles. Venizelos is Crete's most famous son, regarded by many as the greatest of modern Greek statesmen for his role in freeing Greece from Turkish occupation and extending her territories in the early years of the twentieth century.

The graves are simple, unpretentious, lacking in pomp. From the heights you get commanding views of the city of Chania and the great sweep of the bay beyond, as far as the tip of the Rodopos peninsula. But the tombs were not situated here for the view alone, marvelous as it is. Once again, in a way that seems peculiarly Cretan, history and legend interweave. On this spot, in 1897, Venizelos, in the course of leading an insurrection against the Turkish rulers, raised the flag of a united Greece in defiance of the European powers, who still had not consented to the union of Crete with Greece. The flagpole was smashed by a shell from one of the ships in the bay below, but the Cretan rebels took up the flag and kept it flying, braving the enemy fire. The story goes that this so impressed the sailors that they broke into applause, abandoning the guns. It is also related, and in parts of the island still believed, that a Russian shell damaged the roof of the Church of Elijah the Prophet, and that this sacrilegious act brought divine retributionâthe ship exploded the very next day, for no apparent reasonâ¦.

Â

is

NEW

in

CHANIA

Chania is the best place to start when you first come to Crete. It is well placed for seeing the west of the island, which is the region least frequented by visitors, since the coast lacks beaches large enough for tourist development. In recompense you get a sense of remoteness and timelessness here, passing through unspoiled villages, exploring virtually deserted coves, overshadowed constantly by the spectacular presence of the White Mountains, the most imposing range on the island, with a score of peaks that rise to around eight thousand feet, capped with snow from December to June.

The old quarter of the city and the harbor are entirely captivating. In the maze of narrow streets are endless discoveries and surprises, a complex pattern of what has been altered out of all recognition, what has been modified, and what has survived untouched since the Venetians took it from the Genoese in the early years of the thirteenth century, changed its name from Kydonia to La Canea, set about establishing the mansions for their notables that still line the harbor, and constructed the tremendous walls that made the city a bulwark in defense of a maritime empire that was to endure for close on five centuries. The Venetians were great wall builders. You see their work all over the island, with the Lion of St. Mark carved like a trademark over arches and lintels. The massive walls they built to defend the harbor of Chania still stand, as do many of the mansions, now often ramshackle and partly in ruins, or converted to new uses, apartment houses or banks or hotels. During our time in Chania, we stayed in one such hotel, the Casa Delfino, a beautifully converted former palazzo still preserving its paved courtyard, where we had breakfast, its stone staircases, and elegantly arched windows.

Chania: the Venetian harbor

Standing on the old harbor front on a summer evening, facing toward the open sea, with the sun sinking beyond the barren headlands to the west, you are looking at what the earliest inhabitants of this very ancient city saw, the same tints of bronze and fire red and gold that shift across the sheltered water, the same tremulous and fugitive reflections, the same gathering softness in the sky as the light fades. Crete is a harsh land in some ways, unyielding, but its nighttime skies in summer are marked by this indigo softness.

Colors of things, effects of light, these may defy time, but materials do not. The dome of the Mosque of the Janissaries is concrete now, but it still crouches impressively beside the water, with its cluster of lesser domes, a warm biscuit color in the harbor lights, symbol of Ottoman conquest, looking across at the works of its predecessor and rival for empire, still evident in the narrow arched windows and elegant balconies of the houses that the defeated Venetians left behind them.

In general, it is the Venetians who have left their mark on this city rather than the Turks, but the Janissaries were dreaded in their day. This famous corps, the shock troops of the Ottoman Empire in the days of its supremacy, has no parallel in the annals of military history. It was formed in the fourteenth century from Christian slave children, who were converted to Islam, sworn to celibacy, and trained in blind obedience to their commanders and the ruling sultan. In later times, when the central Ottoman power was weakening, discipline was relaxed, they were allowed to marry and granted the privilege of enrolling their children in the corpsâthe best fed and best paid in the army. Levies of Christian youths ceased after the end of the seventeenth century. By the beginning of the nineteenth the Janissaries were completely out of control, a law unto themselves, a public nuisance and a danger to their own rulers. By tradition they used to gather around their cooking cauldrons to take counsel; when these cauldrons were overturned, it was a signal of rebellionâthey would no longer eat the sultan's food. The atrocities they committed on the Cretan populationâwho, as always, resisted the foreign yokeâwere notorious, probably worse than anywhere else in the Ottoman-controlled Greek lands. They were finally destroyed in 1826, shelled out of existence by regular troops of the Turkish army under the command of the formidable Ibrahim Pasha, known by the nickname of Kara Jehennem, “Black Hell.”

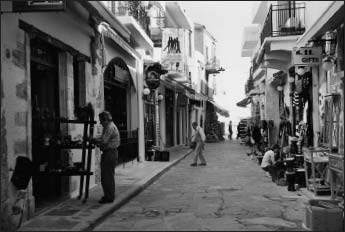

Their mosque in Chania is used now for exhibitions and displays of various kinds. From here to Angelou Street, the old harbor is lined with restaurants, and just about every one of them has a man posted on the pavement outside to solicit the custom of passersby. Anyone who makes this circuit in the summer months will receive instruction in the inventiveness, the inveterate self-defining faculty, of human beings in general and Cretans in particular. The men outside these restaurants, whether young or old, stout or lean, handsome or homely, are aiming at the same thing: They all want to see you seated at one of their tables scanning the menu. But they have adopted a variety of ploys in accordance with temperament. One will assume an earnest manner, even slightly aloof. He doesn't want to tell you how good the restaurant is, only that it has been there since 1961âa fact also proclaimed on a huge placard overhead. Forty years, it seems, is a long time for a restaurant to exist, in this city which has existed for millennia. Another will be loud and direct and boisterous, like a barker at a fair. Another will sound a wistful note as you pass: Sooner or later, today or tomorrow, you will succumb, you won't be able to help yourself. Another waxes confidential, buttonholes you, man to man: Let me tell you something about this place that perhaps you don't knowâ¦. Then there is the action man, who blocks our path, thrusts a menu into our hands.

A Chania street

The Cretans, like their compatriots on the mainland, have a great flair for marketing. They make choosing a restaurant resemble shopping in some vast bazaar. And a sort of bazaar it is, though marked with a curious sameness in the midst of profusion. Cretan restaurant food can be very good and the helpings are generous, butâas opposed to the style of those whose task it is to inveigle you insideâthere is a certain lack of variety in the main courses. Bream or mullet grilled or baked, mutton grilled or stewed, these form the traditional choices. Depending on the restaurant, variety can be found in the range of snacks known as

mezedes,

which are often very good indeed, typically consisting of miniature spiced meatballs and sausages, small triangular-shaped cheese or spinach pies, vine leaves stuffed with rice and pine nuts,

tzatziki

(chopped cucumber, garlic, and yogurt), little saucers of mashed chickpeas or white haricot beans in lemon juice. Still in the exuberant spirit of the bazaar or treasure house, all these items, however small, will be chalked up separately, as if they were main courses, forming long lists on the big slates standing outside. Go inside and you are likely to find them all on one tray. Some restaurants, by no means all, offer Cretan specialties, done as they really should be done: a fish soup called

kakavia

flavored with onion and lemon, a dish called

horta,

which is a judicious mixture of wild greens, some of them bitter and some sweet, gathered fresh from the hillsides, boiled and served cold, with olive oil and vinegar. This may sound simple, but it isn't. When the flavors are blended as they should be, it is superb.

Another very good reason for starting in Chania is that it is distant from the great Minoan palace sites in the central part of the island, remains of a unique and splendid civilization that reached its high point around 1500

B.C.

These must be visited, of courseâthey are what large numbers of people come to Crete for. But there is a lot to be said for approaching from the edge, beginning with the humbler remains that have been unearthed here. Most people, in Minoan times, after all, did not live in palaces, any more than they do today.

Two Minoan sites are being excavated at present in Chania, close together on Kanevaro Street, in the district known as Kastelli, the high ground overlooking the harbor on the eastern side. This is the oldest part of the town, generally believed to be the site of ancient Kydonia, which is the name the Byzantines knew the city by in early Christian times.

Looking at these bare traces, hardly above the level of the ground but demonstrating an order that could never be thought accidental, bearing the unmistakable touch of human design, one has the usual sense of the muteness, the sadness of ruined habitations. The people who lived here were members of a Bronze Age society more advanced than any that had gone before, and any that were to come after for a thousand years. They belonged to the time called by archaeologists the New Palace period, when Minoan civilization was at its most dynamic, when the palaces of Knossos and Festos were being rebuilt after a cataclysmic earthquake, devastation on a scale that would have put an end to a society less vital. The jewelry the well-to-do among these people wore, the textiles and ceramics they used in their houses, have never been surpassed in quality of workmanship and beauty of design. They were not Greeks and their language was not Greek. We call them Minoans, but what they called themselves we don't know. The name we use was given to them by Sir Arthur Evans, the great archaeologist, who named the people after their legendary ruler, King Minos. Evans was the first man to carry out extensive excavations in Crete. He and others worked on sites throughout the island in the early years of the last century, uncovering an entire civilization that had lain unsuspected below the earth and rubble for thousands of years. Together with Schliemann's work on the site of ancient Troy a little earlier, it was one of the greatest enterprises in the history of archaeology.

The buildings whose ruins we peer at through the fence on Kanevaro Street were twice destroyed by fireâperhaps more often, there might have been a long cycle of destruction and rebuilding. The first time known to us was around 1450

B.C.

, when this part of the town was consumed in a great conflagration mysterious in its origins. Minoan sites throughout the island show traces of violent destruction and the scars of fire dating from this time. Natural disaster or the work of invaders or a combination? This is an argument that still goes on.

Poignant evidence that the fire came without much warning is a jar found on the site, containing a quantity of burned peas. A loom was also found, scorched but still recognizable, bringing to mind the peaceful domestic round of the people who lived here, soon to be engulfed. They came back again, in the course of time, from the places where they had found shelter or taken refuge, returned with that tenacity we still see today in the victims of earthquake or flood, who come back to the places they know and painfully rebuild them, seeking to recover the life they had before, which will never again, of course, be quite the same.

Three centuries later these houses were destroyed by fire once again, probably by Greek tribes from the Balkans equipped with iron weapons. This time there seems to have been no recovery, no returnâat least no rebuilding: Any who came back must have lived among the ruins. But the fire, devastating as it must have been, brought with it one unforeseen and startling benefit. On this site, baked by the fire and so accidentally preserved, clay tablets were discovered bearing the written language of the people, what came to be called the Linear A script, pictograms of various plant and animal products. These, in spite of devoted efforts, have not yet been fully understood, but they point to a system of economic administration far in advance of anything else in the world of the Mediterranean at that time.

Then came the further, sensational discovery of tablets of a later date, written in a different script, called Linear B. In the early 1950s, after long efforts by such scholars as Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, this was deciphered and shown to be an early form of Greek, proving the presence here of Mycenaeans from the mainland, who by then had become the dominant power. No other site has been so far discovered containing examples of both scripts. What more lies below this hill of Kastelli can only be conjectured; most of the ancient city of Kydonia has not so far been excavated and is perhaps unlikely to be so now. The streets and houses and shops and office blocks have covered it over.