Crete: The Battle and the Resistance (20 page)

Read Crete: The Battle and the Resistance Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #War, #History

If Colonel Andrew had gone forward before nightfall to observe the coastal strip and the western slopes of Hill 107, he would have seen that Captain Johnson and his men in C Company were still resisting strongly on the airfield, as was Campbell's D Company above the Tavronitis. They had suffered considerable casualties, but having inflicted far greater losses on the enemy, their thoughts were not on withdrawal.

In the area of Prison Valley, the situation was much clearer, partly because Kippenberger, the brigade commander in Galatas, observed the battle in person.

Confusion had existed only around the edges. Genz's glider group, which landed south of Canea to attack the wireless station and antiaircraft batteries, was soon tied down; the catastrophic drop of much of the 3rd Parachute Regiment's III Battalion on top of strong New Zealand positions had created another fine opportunity for killing; and the paratroopers who attacked the 7th General Hospital on the coast had all been killed or taken prisoner. But in Prison Valley itself, the rest of the regiment was well established and had begun to make strong probing attacks along the Galatas and Daratsos heights.

General Weston's rapid decision to bring an Australian battalion from the reserve at Georgioupolis to strengthen the line where Prison Valley opened into a small plain behind Canea was entirely correct.

He put them between the mixed force from the transit camp north of Perivolia (they were dubbed the Royal Perivolians for supposedly saving the King) and the 2nd Greek Regiment on the foothills of the White Mountains.

The 8th Greek Regiment, that exposed 'circle on the map' as Kippenberger called it, held their ground against the German Engineer Battalion extraordinarily well despite their poor armament, and they soon seized the weapons of paratroopers they had killed. Local irregulars, mostly villagers with old sporting guns, fought fiercely to repel an attack on Alikianou. 'Civilians', recorded a German report,

'including women and boys of a total number of 100 approximately participated in the defence.'

On the north side of the valley, the New Zealanders of the Petrol Company on 'Pink Hill' in front of the village of Galatas were forced back by an impetuous attack soon after ten o'clock. But this assault, led by Lieutenant Neuhoff, ended in the virtual destruction of his company.

Pink Hill was so named after the colour of the earth, on which grew couch grass, weeds and lines of yucca like huge caltrops to keep goats out of the vineyards. The trenches there had been dug by the Black Watch six months before, during that energetic period under Brigadier Tidbury. But although Pink Hill formed a strong centre to the 10th Brigade's defence, all the Petrol Company's officers had already become casualties. Kippenberger realized that the drivers and fitters of this composite battalion could not be expected to do more than hold off the enemy; they did not have the training to mount a counter-attack.

Two hours later, Colonel Heidrich, the commander of the 3rd Parachute Regiment, who had set up his headquarters in the prison, directed a scratch force from three companies and Major Derpa's battalion headquarters against the left flank of the Petrol Company and Cemetery Hill, which stuck out between Galatas and Daratsos. They too were repulsed, although with greater difficulty.

There was a lull around lunch-time, almost as if the Anglo-Saxon and German soldiery had become infected by a Mediterranean rhythm. One of Kippenberger's concerns at that time was the fate of the Divisional Cavalry detachment he had positioned up the valley beyond Lake Ayia. But after he had sent out a patrol to bring them in from their isolation, they appeared on their own late in the afternoon, having followed a long, circuitous trek over the coastal hills. They had been able to do little good where they were. Kippenberger immediately put them into the line to replace the Greeks between the Petrol Company at Galatas and the 19th Battalion at Daratsos.

In the valley during that afternoon, platoons from Heydte's battalion attacked up the right-hand side against the 2nd Greek Regiment. They took a hill with an old Turkish fort on top, but soon attracted artillery fire of unpredictable accuracy. The Italian 75s manned round Perivolia had no sights, save an improvisation of wood and chewing gum which might have surprised even Heath-Robinson. They also had no mechanical means of elevation. According to one gunner: 'We just found a bigger stone to shove underneath, if we wanted to increase the range.'

More of Heydte's men probed ahead towards Canea, but they faced the newly arrived Australian battalion as well as the Royal Perivolians from the transit camp. Most of these gunners and rear echelon soldiers, such as fitters and drivers, had never received any infantry training. Some hardly knew how to handle a rifle. But a number of them demonstrated a remarkable instinct for this stalking warfare in the deceptive shadows of the olive groves.

After the lull in the early afternoon, Richthofen's fighters suddenly reappeared, strafing indiscriminately. The German air force's vast expenditure of ammunition and bombs caused much more noise than casualties. Theodore Stephanides, with both medical and human curiosity, observed the phenomenon of a man panicked by an air attack literally running in circles, or ellipses to be exact.

That evening many men were too tired to eat. They just fell asleep once the enemy aircraft departed.

On the German side too, the paratroopers, having dug shallow trenches, bedded down rolled in a parachute. Those cut off behind British lines took advantage of the dark to slip through, ready to whisper

'Reichsmarschall',

the password chosen by General Student in honour of Goering.

Lieutenant Genz, whose glider group from the Storm Regiment had kept the anti-aircraft guns south of Canea out of action for most of the day, led his survivors after nightfall through British units north of Perivolia. They marched openly in a body, but without helmets so as not to be recognized by their silhouettes. Next morning, after a wide sweep, they made contact with elements of Heydte's battalion in Prison Valley.

As night fell on 20 May, the few German commanders who survived in the Maleme—Galatas sector felt they had lost. They had taken neither the airfield of Maleme nor the port of Canea; they had not even taken the small port of Kastelli Kissamou. Their losses had been so disastrous that they believed the strong counter-attack, expected at any moment, would scatter them completely. General Student in Athens was alone in wanting to continue. Richthofen the commander of the VIII Air Corps, Löhr the commander of the IV Air Fleet, and List the commander of the XII Army were convinced that the airborne invasion had been a debacle and that the operation would have to be aborted.

Freyberg's failure to launch a vigorous counter-attack that night is one of the most vexed questions of the battle. One reason is that he was misinformed by Brigadier Hargest, whose persistent refusal to take Colonel Andrew's warnings seriously still cannot be explained satisfactorily. Yet Freyberg seems to have shown little interest in Maleme, some say because he had become convinced that the Germans intended to crash-land their transports and that therefore possession of an airfield was irrelevant. That even the Germans could afford to be so profligate — their whole transport fleet would have been destroyed in two days — was indeed a curious idea.

Only one counter-attack was attempted. This took place at dusk on Puttick's orders following an inaccurate report that paratroopers were trying to construct a landing strip in Prison Valley. Amid much confusion, two companies and three light tanks — a pathetically inadequate force — were sent against Heidrich's parachute battalions numbering nearly 1,300 men. Attempts to cancel the operation failed at the last moment, and patrols roamed throughout the night trying to find the company commanders to tell them. Platoons lost contact with each other in the dark, and the outcome was a number of random and chaotic clashes, fortunately with the enemy rather than each other.

11

Close Quarters at Rethymno and Heraklion

20 May

At Heraklion on that first morning, the 'daily hate' did not turn out to be the prelude for parachute drops as at Canea. Companies were stood down for breakfast, and the skies remained clear of aircraft.

As the morning progressed uneventfully, the 14th Infantry Brigade relaxed. General Freyberg had not dared pass on to his brigade commanders the information gleaned from Ultra that the Germans had finally fixed the operation for 20 May. In any case it was assumed that an airborne invasion would come soon after first light, and no word had arrived from Creforce Headquarters of glider landings or parachute drops at their end of the island.

Members of Chappel's headquarters staff not on duty received permission to leave the quarry. One of the intelligence officers, Gordon Hope-Morley, a keen botanist, set off in search of wild flowers: he took his camera, which later came in useful, but not his rifle or steel helmet which would have been more appropriate. Officers in the three British infantry battalions also set off, some to pay purely social calls on friends in other companies, others on the more serious purpose of reconnoitring the surrounding countryside. The Leicesters, who had arrived at the last moment, badly needed to 'walk the course'. Their commanding officer, on the other hand, decided that this was the ideal opportunity to slip into Heraklion for a bath in the principal hotel.

On the mainland, the commanders of the 1st and 2nd Parachute Regiments became increasingly impatient as they waited beside their airfields. Colonel Bruno Bräuer, charged with the assault on Heraklion, did not hide his displeasure at the delay. Bräuer, shorter than most paratroopers, was known for his slight stammer, his cigarette-holder and his bravery. During the capture of Dordrecht in Holland, he had ignored advice to shelter from enemy fire with the curious dictum: 'Paratroopers never come under fire!'

Colonel Alfred Sturm, an older man inclined to stand on his dignity, resented the low priority accorded to his attack on the town of Rethymno and its landing strip. His 2nd Parachute Regiment had captured the Corinth isthmus, yet now he had to hand over a battalion to Bräuer.

The delays during the early morning departures for Maleme and the Ayia valley accumulated during the course of the day. And when the Junkers returned from their mission, the bullet holes in fuselage, wings and tailplane were not only chastening to behold, they also required time to repair.

Since there were no petrol bowsers, the tri-motors had to be refuelled by hand. To speed up the operation, paratroopers were told to lend the ground crews a hand. This order provoked angry disbelief, but the soldiers stripped off to their gym shorts and sweated away at the work with the temperature at forty degrees centigrade in the shade. The sun had become so hot and evaporation so rapid that attempts to water the runway and dispersal areas to keep down the red dust proved futile.

For the paratroopers still in their full jumping gear, the discomfort was considerable. And the planes, when the time eventually came for boarding, were like ovens.

Most of the paratroopers had not even emplaned at two o'clock, the time they were supposed to be over the Heraklion and Rethymno dropping zones. And when the first wave took off, the dust clouds caused even more hold-ups than the night before. In a couple of cases aircraft collided on the runway.

The times between take-offs became crucial at the other end, since every extra minute gave the defenders more time to deal with one drop before the next wave was upon them. Once airborne, few paratroopers in Group East felt like singing

'Rot scheint die Sonne'.

Bräuer was on the last wave of fifteen aircraft to leave. He was furious. Because of a shortage of aircraft, 600 men had had to be left behind: Group East now had only 2,300 men.

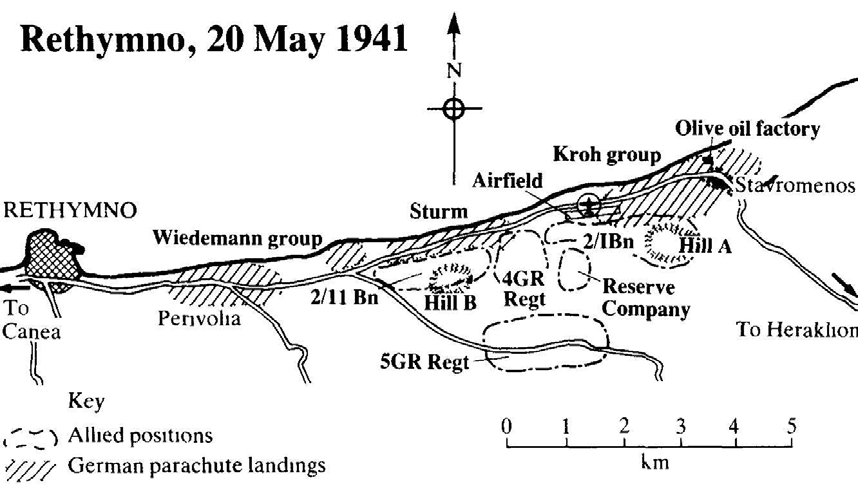

Colonel Sturm, although he resented losing one of his battalions to Bräuer, faced less fearsome odds at Rethymno. He decided to keep a reinforced company under his personal command, and divided the rest of his force into two battle groups, one led by Major Kroh and the other by Captain Wiedemann.

Both were based on battalions which had captured the Corinth isthmus the month before. Kroh's battle group was to land to the east of the airfield then take it. Wiedemann's slightly stronger force was to land between the airfield and Rethymno to capture the town and port dominated by a strong Venetian fortress.

The defence of the Rethymno area was the responsibility of a young, recently promoted Australian regular - Lieutenant Colonel Ian Campbell. He left the defence of the town itself to 800 members of the Cretan gendarmerie, a well-disciplined and very effective force. The defence was directed by Major Christos Tsiphakis, a Cretan officer who was to play a major part in organizing the resistance during the occupation. To hold the airstrip, which lay eight kilometres east of the town between the coast road and a line of hills, Campbell had two Australian battalions and two machine-gun platoons

— some 1,300 men - together with 2,300 Greek soldiers, as ill-armed and inexperienced as their counterparts elsewhere.

Campbell's own battalion, the 2/1st, and half a dozen field guns, well-hidden in the terraced vineyards on the hillsides, could cover the landing strip while remaining concealed. Aerial reconnaissance spotted only one of their positions, and that was changed. The other battalion, 2/1 lth, commanded by Major Ray Sandover, was sited on another coastal hill three kilometres closer to the town. A Greek regiment filled the gap. The rest of the Greeks and two Matilda tanks were hidden in olive groves on the rear slope of the ridge.