Crete: The Battle and the Resistance (21 page)

Read Crete: The Battle and the Resistance Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #War, #History

To give their soldiers a break in the days of waiting before the invasion, Campbell and Sandover sent them off to swim in parties of less than twenty at a time in case of air reconnaissance. On their return, with the forward platoons stood to, they had to try to creep back without being seen. This enabled the defenders to identify in advance pockets of dead ground and likely routes of attack. The ridge's many gullies, which following their desert experience the Australians called wadis, were numerous and dangerous.

With few other diversions to occupy the time, Campbell and Sandover had to get a grip of their heavy-drinking and pugnacious men. The town of Rethymno, where several fights had broken out in cafes, was put out of bounds and provost patrols were instituted.

On 20 May, the air attack began at four o'clock in the afternoon. With no more than twenty fighters and light bombers, it was a desultory affair. A few of the Greek recruits panicked, but a handful of Australian NCOs sent across by Campbell soon brought them back into line. At 4.15 p.m. the troop carriers appeared over the sea. They then swung in from the Heraklion side and began to drop their paratroopers at between three and four hundred feet.

The Junkers followed the coast road towards Rethymno. This meant that they passed close to the hillsides full of concealed positions. Out of about 160 aircraft, seven were brought down along the beach, and others sheered off in flames over the sea. One platoon commander was killed in the doorway on the point of jumping. His men were so unnerved that they refused to jump. The pilot then came round for another run over the dropping zone, but one of his engines was hit and caught fire.

Soon the whole wing was in flames, so he crash-landed in the sea close to the beach. Paratroopers and crew climbed into a rubber dinghy, but the shooting did not stop. In the end only two escaped.

An already disrupted operation had became chaotic. Some paratroopers dropped into the sea where, weighted down by equipment and smothered by their own silk canopies, they quickly drowned. Many of those who fell slightly inland suffered injury landing on the rocky terraces. The most horrific fate befell about a dozen men who came down in a large cane-brake where they were impaled on bamboos.

Out of the whole force, only two companies were dropped in the right place. They were part of Kroh's battle group, destined for the airfield, and thus landed directly in front of Campbell's positions. The survivors of this disaster had slipped into the scrub and gone to ground. One lieutenant wanted to give the order to surrender, but a sergeant curtly replied: 'Out of the question.' The survivors were later assembled by Lieutenant von Roon who led them on a circuitous journey inland to join up with Major Kroh's men.

The main part of Kroh's force fell round the olive oil factory at Stavromenos, two kilometres to the east. Kroh, who had come down even further along the coast, gathered his men as quickly as possible and marched in to attack the main hill — called Hill A — which formed Campbell's flank. On the way, he encountered Lieutenant von Roon, who had gathered more men in spite of skirmishing attacks from Cretan irregulars. Kroh's paratroopers, with local superiority and better weapons, overcame the defenders and killed most of the field gun and machine-gun crews. The vineyards provided good cover for attackers as well as defenders.

Campbell did not lack decisiveness. He deployed half his reserve company and the two Matildas in a rapid counter-attack. The tanks, in another anti-climactic appearance, proved themselves as useless on rough ground as at Maleme, but the rapid deployment of infantry managed to prevent the Germans from advancing. That evening, he contacted Creforce Headquarters by wireless to ask for help but Freyberg did not want to commit the remaining Australian battalion at Georgioupolis. Campbell, knowing that everything would depend on the next morning, prepared to use every spare man he had in a counter-attack to throw the Germans back off Hill A.

Colonel Sturm's group of nearly two hundred men had dropped in front of Sandover's battalion and suffered a fate similar to that of those landing on the airfield. All twelve members of a stick from one aircraft were dead by the time they touched the ground. Sturm and his immediate headquarters staff were saved only because they dropped into a small patch of dead ground. Shortly before nightfall, Sandover advanced with his whole line to clear the area. Eighty-eight prisoners were taken and a large quantity of weapons collected. Sturm himself was captured the next morning.

The same morning, 21 May, Campbell launched his counter-attack on Hill A using all reserves, with the two Greek regiments supporting on each flank. Just before the assault commenced, a German bomber pilot mistook a paratroop position and killed sixteen men. This sight encouraged Campbell's Australians who soon charged with ferocious determination. Kroh's paratroopers were swept back and withdrew to the olive oil factory at Stavromenos, which they used as a fort.

Both Australian battalions then carried out a mopping-up operation and managed to capture most of the survivors. Only a few small groups were left. Major Sandover, walking down a track afterwards, came across a message chalked on the road in German: 'Doctor urgently needed'. Sandover's companion spotted a small cave and, finding that it contained six wounded paratroopers, pulled out a grenade to finish them off. Sandover stopped him, and called for them to be taken to the regimental aid post. The paratroop medical unit had also been captured, and within a few days a joint field hospital developed tending several hundred patients, German, Australian and Greek together.

Colonel Sturm, 'a very shaken man' on capture, was further dismayed when, during Major Sandover's interrogation in German, he discovered that the Australians had found a full set of operational orders on the body of one of his officers. Sandover found him trying to look over his shoulder to see who could have committed such a blunder. From another officer, Sandover discovered that there were no paratroop reserves to come. 'We do not reinforce failure,' said the German.

Meanwhile, Wiedemann's battle group, which had landed a couple of kilometres closer to Rethymno, did not fall into a trap like the others but soon came up against the Cretan gendarmerie from the town and 'unrecruited civilians' on the southern side. Unable to advance without crippling loss, Wiedemann ordered his men to prepare a 'hedgehog' defence round the seaside village of Perivolia.

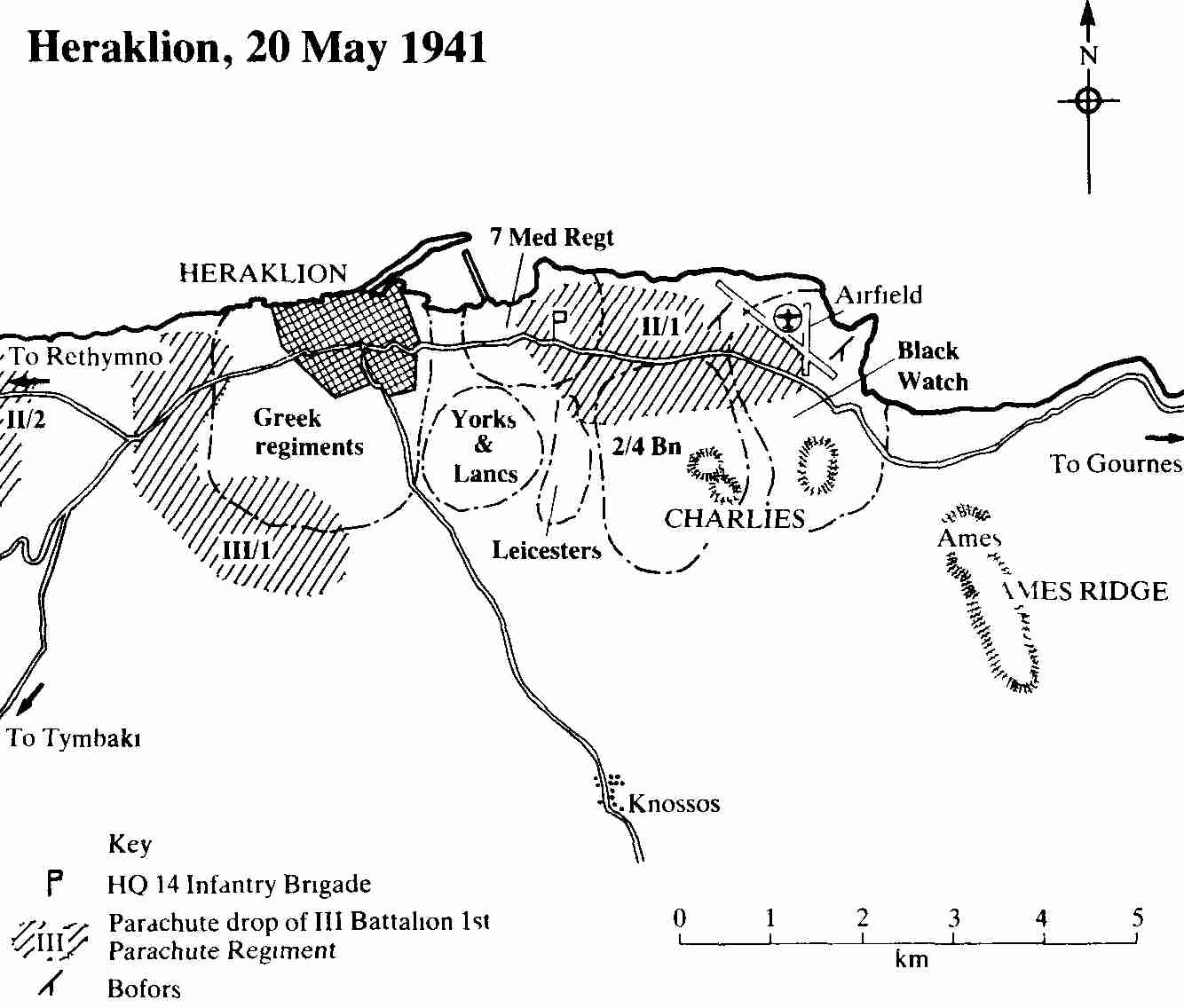

News of the parachute drops on Maleme and Prison Valley finally reached Brigadier Chappel's headquarters outside Heraklion at 2.30 p.m. The Leicesters managed to retrieve their commanding officer from his bath in town, but many of the other officers absent from their units remained out of contact.

At four o'clock, German bombers arrived in large numbers, and a few minutes later the warning

'Super Red' arrived from the radar station on the ridge two kilometres to the south-east of the airfield.

Stuka dive-bombers began to attack at 4.12 p.m., and at 4.34 p.m., according to the Black Watch war diary, twin-engined Messerschmitt 110s started strafing.

Casualties were few. The positions were well camouflaged, as captured maps and aerial reconnaissance photographs later proved. And soldiers, in a measure designed mainly to conserve ammunition, were forbidden to open fire on aircraft with small arms. (Later in the battle this order was rescinded in the interests of morale.) More importantly, the anti-aircraft guns around the airfield perimeter — a dozen Bofors manned by Australian and British gunners, and a Royal Marine battery of 3-inch guns and pom-poms — had remained silent, unlike at Maleme. Chappel's ruse managed to convince the Germans that their previous raids on the gun emplacements had put them out of action.

After less than half an hour, the Stukas returned to their base on the island of Skarpanto to the east of Crete and the Messerschmitts turned back over the Aegean; neither could wait for the long-delayed troop-carriers.

Those British officers away from their units, whether on official or unofficial business, breathed a sigh of relief that this had been just another air raid. But shortly before 5.30 p.m., the company commander of the Leicesters out with his platoon commanders was horrified to hear a bugler in the distance sound 'general alarm'. This was the signal for an imminent parachute attack: by wireless or field line, the code was 'Air Raid Purple'. His dismay was greatly increased by the fact that Brigadier Chappel had given the Leicesters the task of immediately mounting any counter-attack that might be required.

The slow rumble of the approaching wave of Junkers increased to an oppressive roar as the specks out over the sea grew to recognizable silhouettes. In their flat 'V formations of three, the troop-carriers banked to turn for their run along the coast, spilling out long dark streaks which, with a sudden jerk, blossomed into canopies. The gasps of astonishment at the sight were no different from those round Canea earlier in the day.

Rifle fire broke out from all the concealed positions along several miles of coast. To the east of Heraklion on the airfield side, Captain Burckhardt's II Battalion dropped more or less following the line of the coast road. They jumped from around level with the quarry containing brigade headquarters. Their dropping zone spread across almost every British and Dominion regiment in the garrison — over part of the 7th Medium Regiment, over part of the Leicesters, over part of the 2/4th Australian Battalion, and then the bulk fell on the Black Watch, the largest battalion and the one responsible for the airfield.

Anti-aircraft guns suddenly opened fire on the slow-moving targets. Paratroopers tried to jump from one Junkers 52, which had caught fire, but their canopies never opened. The Australian infantrymen on 'the Charlies' — two supposedly breast-shaped peaks of jagged rock overlooking the west end of the airfield — were firing almost horizontally at the tri-motors as they flew past. The white faces of the crew were clearly visible. 'They looked so close, it felt as if you could almost touch them,' was a common remark afterwards. The Australians had stretched a strand of barbed wire between the summits of the two hills, and although several aircraft came close, none became snagged.

In this extraordinary fusillade, many opened fire wildly at first, but then, with a feverish self-control, soldiers selected their targets, whose gentle swayiqg camouflaged the speed of their descent. They fired, reloaded and fired again at paratroopers who may already have been dead. Unlike the terrain round Maleme and Prison Valley, there were few trees or telegraph poles to snag chutes, but there was little cover. Germans were riddled as they struggled free of their harnesses.

The battle was of course not restricted to front-line sections and platoons. Paratroopers were just as likely to come down on top of a company or battalion headquarters, where officers used rifles as well as service revolvers. For officers and soldiers alike it offered a perfect opportunity for laconic humour in the thick of a fight. When one Black Watch command post at last received official notification of the parachute attack, the 'signaller said solemnly to Captain Barry (who had just shared three Germans with Lieutenant Cochrane): "Air-raid warning Purple, sir."

Because of the delays that disrupted take-off from the mainland, the drop continued for two hours.

Without Messerschmitts and Stukas to worry about, the Bofors gun crews traversed on to the lumbering Junkers 52 troop-carriers with grim glee. The Black Watch war diary recorded at 7.07 p.m.

that eight of them could be seen going down in flames at the same time: but since the Germans lost a total of fifteen aircraft in two hours, this figure is probably more enthusiastic than reliable. Yet even fifteen aircraft lost to groundfire in one action must still have been a record. It was more than double the combined total of those shot down at Maleme, Suda and Galatas.

Burckhardt's paratroopers who fell in the open spaces round the aerodrome, such as a turnip field, had to run for their weapon containers in full view. Those who fell into low cover, such as the field of barley near the runway, survived a little longer. Movements in the corn and frantic animal rustlings indicated their positions, and soon incendiaries were used to flush them out like rabbits at harvest time. A company with Bren gun carriers went hunting in a vineyard, but the Germans there were able to stalk them in return and lob grenades.

At 6.15 p.m. Brigadier Chappel told the Leicesters to send fighting patrols to comb 'Buttercup Field'

east of the quarry. Out of Captain Dunz's reinforced company, only five survivors managed to escape.

Throwing themselves into the sea, they shed their kit and swam round to rejoin Major Walther's I Battalion eight kilometres further east along the coast at Gournes, where it had been dropped to capture a wireless station.

But the fighting towards the airfield was not a complete walkover. Chappel had made a mistake similar to Kippenberger's failure to occupy the prison in Ayia valley. He had not put troops into buildings on either side of the coast road, including an abandoned barracks and a slaughter-house.

These soon provided shelter and defence for a few groups of survivors who needed winkling out later.