Criminal Minds (2 page)

Authors: Jeff Mariotte

Instead, they’ re the dregs, barely worth discussing, for the most part. However, they’re fascinating to examine as case studies, in some perverse way—for the same reason we go to horror movies, one supposes, to see at a safe distance things we hope never to encounter in our own lives. As noted FBI profiler John Douglas points out in several books devoted to his work, the better we can understand these human predators, the better we as a society can protect ourselves from them and try to prevent them from doing the things they do.

Within the five seasons of

Criminal Minds

(as of this writing), there have been two fictional serial killers who avoided arrest the first time they appeared, only to become serious threats to two of the show’s main characters. Readers familiar with the series will recall Frank Breitkopf; he was introduced in the episode “No Way Out” (episode 213) but escaped, only to return in “No Way Out II: The Evilution of Frank” (223) and kill a close friend of Supervisory Special Agent Jason Gideon.

Criminal Minds

(as of this writing), there have been two fictional serial killers who avoided arrest the first time they appeared, only to become serious threats to two of the show’s main characters. Readers familiar with the series will recall Frank Breitkopf; he was introduced in the episode “No Way Out” (episode 213) but escaped, only to return in “No Way Out II: The Evilution of Frank” (223) and kill a close friend of Supervisory Special Agent Jason Gideon.

Then there’s George Foyet, known as the Reaper, who first appeared in “Omnivore” (418) as unit chief Aaron Hotchner’s nemesis; he eventually murdered Aaron’s wife, Haley. Aaron beat him to death with his bare hands, in the powerful 100th episode of the series, titled simply “100” (509).

As of this writing, Karl Arnold, known as the Fox, has also made more than one appearance; introduced in “The Fox” (107), he returned in “Outfoxed” (508), but he’s in jail and not currently a threat.

Breitkopf and Foyet are both brilliant, brutal men, “ideal” killers with no real-life analogues. One possible parallel to Foyet might be one of the people most frequently mentioned on the series: David Berkowitz, popularly known as the Son of Sam, one of the most notorious serial killers of all time. The fictional BAU profilers on the series refer to Berkowitz in seven episodes: “Extreme Aggressor” (101), “Compulsion” (102), “Unfinished Business” (115), “A Real Rain” (117), “The Last Word” (209), “Lo-Fi” (320), and “Zoe’s Reprise” (415). Only the names Ted Bundy and Charles Manson come up more often.

DAVID BERKOWITZ

DAVID BERKOWITZwas determined to name himself to the New York Police Department (NYPD), but at first he appeared uncertain about what name he wanted to use. New Yorkers had started calling him the .44 Caliber Killer, because he was killing women with a Charter Arms .44 Bulldog handgun. In a letter addressed to NYPD captain Joseph Borrelli that was left at the scene of two murders, Berkowitz wrote, “I am the Son of Sam,” but he also wrote “I am the ‘Monster’—Beelzebub—the chubby behemouth.” A skilled speller Berkowitz was not. He signed his introductory missive “Mr. Monster.” He was indeed a monster, but Son of Sam was the name that stuck.

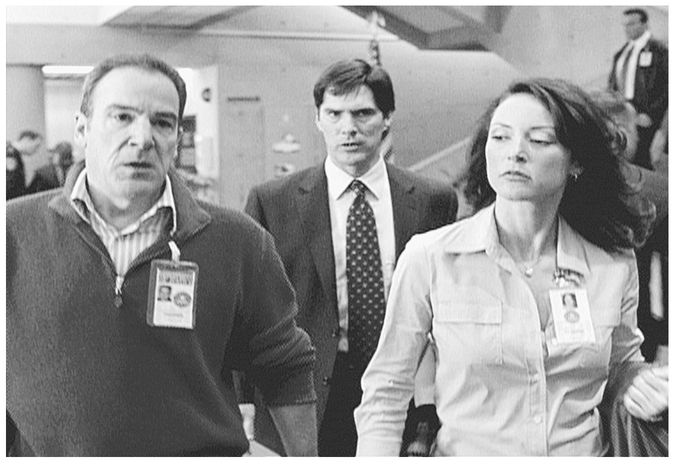

In the

Criminal Minds

premiere episode, “Extreme Aggressor,” Agents Gideon, Hotchner, and Greenaway must profile a serial killer to find a missing woman before she becomes his next victim.

Criminal Minds

premiere episode, “Extreme Aggressor,” Agents Gideon, Hotchner, and Greenaway must profile a serial killer to find a missing woman before she becomes his next victim.

Berkowitz began his criminal career stealing from his adoptive mother, Pearl Berkowitz, and committing petty vandalism. He shoplifted things his parents would have bought him, and he poisoned his pet fish, fed rat poison to his mother’s parakeet, and created a torture chamber for any insects unlucky enough to cross his path. Later in life, after Pearl had died and David’s adoptive father, Nathan Berkowitz, moved away with his new wife, David became even more dangerous. Between September 1974 and December 1975, according to detailed diaries he kept, Berkowitz set 1,488 fires in New York City and pulled hundreds of fire alarms. He enjoyed the power, the ability to upend people’s lives and to make the great city’s resources respond to his will.

Common early indicators of serial murder are bed-wetting, fire-starting, and animal torture, sometimes called the McDonald Triad (after psychiatrist J. M. McDonald, who described it in a professional journal) or the triad of sociopathy. Berkowitz had two out of three.

His first murder attempt was a failure. On December 24, 1975, he took a hunting knife back to the apartment complex he had lived in with his adoptive father and stabbed a young woman in the back. Instead of dying in an appropriately cinematic fashion, she screamed. Berkowitz fled the scene, dissatisfied. His account of this stabbing has never been confirmed, and the victim has never been identified. A short while later, with the urge still strong, he crossed paths with fifteen-year-old Michelle Forman and took another crack at it. He stabbed Forman six times. Like his previous victim, she screamed but didn’t die. After that, Berkowitz changed weapons. He wouldn’t be a stabber after all, but a shooter.

His next attempt proved more successful. He had started to regularly cruise New York’s streets, searching for victims. Early in the morning on July 29, 1976, he shot two teenagers, eighteen-year-old Donna Lauria and nineteen-year-old Jody Valenti, while they sat in Jody’s car outside the Lauria home in the Bronx. Berkowitz claimed that he didn’t know for sure if he had killed them until he read about the shooting in the newspapers, but he had managed to kill Donna and shoot Jody in the thigh. After the shooting, he returned to his apartment and slept soundly.

Most serial killers have a cooling-off period after a murder, and Berkowitz was no exception. By September, he had heated up again and returned to the hunt. His next target was Rosemary Keenan, eighteen, the daughter of a police detective who would later become part of the task force hunting Berkowitz. On October 23, Keenan and her friend Carl Denaro were parked outside her home in Queens. Berkowitz, using the Charter Arms .44 that would become his trademark, fired repeatedly into the parked car. Keenan, in the driver’s seat, was unhurt, but Denaro was hit in the back of the head. He lived, but he had to have a metal plate put in his skull, and his air force career ended before it began.

Between then and the end of January 1977, Berkowitz struck twice more, killing Christine Freund, twenty-six, and injuring three others.

By this time, the police were beginning to suspect a connection among all these shootings. Although they were spaced out in time and there were no connections among the victims, they had all been shot with .44 bullets. Most of the victims were young women with long dark hair. In the cases in which Berkowitz had shot at men, they were with young women. Most were sitting in parked cars.

Things were changing in Berkowitz’s life, too. Before the shooting rampage started, he had sent a letter to Nathan. In it he wrote, “Dad, the world is getting dark now. I can feel it more and more. The people, they are developing a hatred for me. You wouldn’t believe how much some people hate me. Many of them want to kill me. I don’t even know these people, but still they hate me. Most of them are young. I walk down the street and they spit and kick at me. The girls call me ugly and they bother me the most. The guys just laugh. Anyhow, things will soon change for the better.”

After the murders, things looked brighter to him, at least for a little while. Berkowitz had worked menial jobs in construction and security and had then driven a cab, but shortly after he killed Christine Freund, he did well on a civil service exam, which enabled him to become a postal employee and earn the highest salary of his life. Like the fictional George Foyet and many real serial killers, Berkowitz was a man of above-average intelligence working at jobs below his real capabilities. Also like Foyet, although Berkowitz attacked victims of both sexes, he was most interested in his female victims.

Berkowitz ordinarily hunted late at night or early in the morning, but his next murder took place on March 8, 1977, at 7:30 p.m., not far from where he had shot Freund. He was on foot and saw Virginia Voskerichian, a nineteen-year-old student, walking toward him. He pulled his .44. Voskerichian held her books up to shield herself, and Berkowitz shot her in the face.

Two days later, Mayor Abe Beame joined the NYPD brass for a press conference, at which they announced the formation of the Operation Omega task force. Its only goal was to find the man or men doing these shootings.

About a month later, a letter was delivered to Sam Carr, a retired municipal worker who lived in Yonkers in a house behind the apartment building where Berkowitz lived. The letter complained about Carr’s dog, Harvey, a black Labrador that was constantly barking. The importance of this communication wouldn’t become known until much later.

The next incident, on April 17, was the occasion on which Berkowitz left the first “Mr. Monster” letter for Captain Borrelli. Berkowitz left behind the dead body of Valentina Suriani, eighteen. Her companion, Alexander Esau, twenty, held on for almost a day before he died.

Two days later, Carr received another letter that complained about his apparent unwillingness to control Harvey. “Your selfish, Mr. Carr,” the letter said. “My life is destroyed now. I have nothing to lose anymore. I can see that there shall be no peace in my life, or my families life until I end yours.”

On April 29, someone shot Harvey. Carr rushed the dog to a vet, who was able to save its life. Because the Borrelli letter had not yet been made public, Carr had no way to connect his own letters to the .44 Caliber Killer.

The existence of the Borrelli letter was not a secret for long. Columnist Jimmy Breslin wrote about it, noting that the writer—the so-called Son of Sam—habitually spelled women “wemon.” The letter also referred to “father Sam,” who got mean when he was drunk. There would be much more talk about Sam in the weeks to come.

For his attention, Breslin got a note directly from Berkowitz, who wrote the following:

Hello from the cracks in the sidewalks of NYC and from the ants that dwell in these cracks and feed in the dried blood of the dead that has settled into the cracks.

Hello from the gutters of NYC, which is filled with dog manure, vomit, stale wine, urine, and blood. Hello from the sewers of NYC which swallow up these delicacies when they are washed away by the sweeper trucks.

Don’t think because you haven’t heard for a while that I went to sleep. No, rather, I am still here. Like a spirit roaming the night. Thirsty, hungry, seldom stopping to rest; anxious to please Sam.

The publicity sold newspapers. Because Berkowitz preyed on brunettes, blond wigs sold out at stores all across New York. Thousands of worthless tips swamped the task force.

Berkowitz reached out by mail again in early June, when a New Rochelle man named Jack Cassara received a get-well note, ostensibly from Sam and Francis Carr in Yonkers. The note included a picture of a German shepherd and referred to Cassara’s fall from a roof.

Cassara found this strange. He didn’t know the Carrs, and he had not fallen from a roof. He found out that the Carrs were real people and gave them a call. Jack Cassara and his wife, Nann, and their son Stephen met the Carrs at the latter’s home, where the Carrs described what had happened to Harvey and to a neighborhood German shepherd, which had also been shot. The Carrs’ daughter, Wheat, a dispatcher for the Yonkers police, summoned officers Peter Intervallo and Thomas Chamberlain to look into things.

Something about the situation reminded Stephen Cassara of a strange man who had rented a room in the Cassaras’ house in 1976. The man, David Berkowitz, had never liked the Cassaras’ German shepherd, and he had moved out abruptly, never coming back for his two-hundred-dollar security deposit. Nann Cassara became convinced that Berkowitz was the Son of Sam but couldn’t get the police to take her seriously.

Then another strange letter—this one to a deputy sheriff named Craig Glassman, a neighbor of Berkowitz’s in the same apartment building—described a “demon group” that included Glassman, the Carrs, and the Cassaras. Intervallo and Chamberlain decided to check out this Berkowitz character. They found his current address, learned the registration number of his Ford Galaxie, and discovered that his driver’s license had recently been suspended. That was as far as their investigation went, for the moment.

On the morning of June 26, 1977, Judy Placido, seventeen, had just left the Elephas disco with her date, twenty-year-old Sal Lupo. They were sitting in Lupo’s car when the Son of Sam fired three shots into the car. Neither was seriously injured. Witnesses reported two people leaving the scene: a tall, stocky dark-haired man running and a blond man with a mustache driving a car without headlights.

Other books

The Adventurer by Jaclyn Reding

The Enemy Inside by Vanessa Skye

SUMMATION by Daniel Syverson

Good-bye and Amen by Beth Gutcheon

Miss Julia Inherits a Mess by Ann B. Ross

Ordinary Light A Memoir (N) by Tracy K. Smith

A World Elsewhere by Wayne Johnston

Blue Molly (Danny Logan Mystery #5) by M.D. Grayson