Criminal Minds (8 page)

Authors: Jeff Mariotte

If the fictional Perotta were compared to real-life Mafia hit man Roy DeMeo, Perotta would be a piker.

Exact figures are hard to come by, for obvious reasons, but DeMeo is suspected of between seventy-five and two hundred murders. A Neapolitan rather than a Sicilian, he grew up around mobsters in Bath Beach, Brooklyn, in the early 1940s, and he worked his way into their good graces. He was close to a Gambino family associate named Nino Gaggi, and with Gaggi’s sponsorship eventually became a made man (someone officially inducted into the Mafia). As a young man he was violent, aggressive, and strong.

Working for the Gambino family, DeMeo put together his own crew, specializing in auto theft and drug trafficking (an activity of which Mob boss Carlo Gambino disapproved). At age thirty-two, DeMeo did his first hit, a simple execution: several bullets to the head, the body left in an alley.

DeMeo realized that some bodies shouldn’t be found, so he developed a method to dispose of them that rivaled Henry Ford’s advances in the mass production of automobiles. DeMeo owned a bar called the Gemini Lounge; it had an adjoining apartment, and the bathtub sometimes came in handy. Because his crew performed their grisly tasks there (sometimes referring to the place as the Horror Hotel), their technique became known as the Gemini Method.

When they had a victim whom they needed to disappear, he would be shot in the head. Immediately, another member of the crew would wrap a towel around the head to stanch the flow of blood. Someone else would stab the victim numerous times in the heart in order to make sure the victim was dead and stop his heart from pumping. He would be put in the bathtub, or hanged over it, so that the blood would drain into a controlled location and be easily washed away. The drained body was then beheaded, cut into pieces (DeMeo, once a butcher’s apprentice, knew about chopping meat), wrapped in garbage bags, and tossed.

The first time DeMeo’s butchers tried this method, they made a couple of mistakes. One of the crew put the victim’s head through a compacting machine, an unnecessary bit of overkill. Once the victim was bagged, they tossed him into a Dumpster, believing that it would be emptied soon. When it wasn’t, a homeless man came along and opened the bags, then fled. The next passerby called the police. After that point, the Gemini crew delivered packages directly to the garbage dump or buried them beneath buildings under construction. The disassembly crew enjoyed its work and was good at it. Between 1977 and 1979 these men plied their trade almost nonstop.

The FBI whittled away at the Gemini crew, and finally Gambino decided that DeMeo’s habits were drawing undue attention to family matters. DeMeo, like so many of the people he had met in the last decade, was executed. He was shot seven times, and his body was left in the trunk of a car that was abandoned at a boat club. DeMeo wouldn’t be allowed to disappear the way his victims had—he was used to send a final message.

DeMeo associate Richard Kuklinski, also known as the Iceman, would also put Perotta to shame. Kuklinski was ten years old when his alcoholic father, Stanley, beat his older brother, Florian, to death. Young Richard and his mother lied about Florian’s cause of death in order to protect Stanley from the law. By age fourteen, Kuklinski had committed a murder of his own. Before his career came to an end, he claimed credit for at least 130; some sources put it closer to 200.

Kuklinski’s favorite murder weapon was cyanide, because it was hard to detect postmortem. But he was flexible, so he also used guns, knives, chain saws, and even a crossbow on at least one occasion. In his nearly scientific quest for murderous perfection, he sometimes froze the bodies of his victims to disguise their times of death, thereby earning himself the nickname the Iceman.

Kuklinski died in prison in 2006, reportedly of natural causes, but he was preparing to testify against Gambino family underboss Sammy Gravano. After the Iceman’s death, the charges against Gravano were dropped for lack of evidence.

Although people like Roy DeMeo and Richard Kuklinski—and the fictional characters Vincent Perotta and Tony “Basola” Mecacci, the Mob enforcers from “Reckoner” (503)—are not typically counted among the ranks of serial killers, they share many traits with them. Most notably, they suffer from a sociopathic lack of empathy. They feel no remorse about their victims, no sense of loss about lives snuffed out before their time. DeMeo and Kuklinski killed more for business reasons than personal ones, but they couldn’t have racked up the body counts they did if they weren’t supremely damaged human beings. In Kuklinski’s case, especially, the cause of that damage is obvious. Both men were, as the title of the episode suggests, natural-born killers.

2

Sexual Predators: Female Victims

THE MOST FREQUENTLY

encountered unsubs on

Criminal Minds

are sexual predators. This might be because their particularly heinous crimes make dramatic television. When sex and death are mixed up, the result can be prolific serial killers whose fantasies lead them to kill and who refuse to stop. Some serial sexual predators focus on women, whereas others prey on men. What they have in common is the overriding urge behind their actions. They’re killing out of lust, and in most cases they’re powerless to stop themselves.

encountered unsubs on

Criminal Minds

are sexual predators. This might be because their particularly heinous crimes make dramatic television. When sex and death are mixed up, the result can be prolific serial killers whose fantasies lead them to kill and who refuse to stop. Some serial sexual predators focus on women, whereas others prey on men. What they have in common is the overriding urge behind their actions. They’re killing out of lust, and in most cases they’re powerless to stop themselves.

ONE KILLER

ONE KILLERwho broke that final rule—who stopped himself cold, once he had dispatched the person at whom his anger was really directed—was Edmund Kemper, the Santa Cruz contemporary of Herbert Mullin’s. Kemper, the Coed Killer, is referred to by Aaron Hotchner as an example of a spree killer in the

Criminal Minds

episode “Charm and Harm” (120) and again, by David Rossi, as a killer with some characteristics similar to those of the unsub in “Penelope” (309).

Edmund Emil Kemper III was born on December 18, 1948, and it wouldn’t be long until he killed his first victims—his own grandparents. Since his parents’ antagonistic relationship had ended in divorce, Kemper’s psychological problems—no doubt intensified by living with a mother, Clarnell Kemper, who constantly belittled and demeaned him—grew worse. He had two sisters, one older and one younger, and he used to play a death-ritual game with the younger in which he would pretend to be strapped into a chair in a gas chamber. She would release the poisonous gas, and he would struggle and writhe until he “died.” When his sister teased him about a crush on a female teacher, he said, “If I kiss her I would have to kill her first.” He was already, at a young age, beginning to have fantasies that interwove murder and sex.

When Kemper was an adult, he was six feet nine and weighed almost three hundred pounds. But when he was a child, his mother, fearing that her already oversized son would sexually assault his sisters, made him move his belongings into the basement and sleep there, locked in. Her various marital adventures didn’t help; Kemper’s successive stepfathers didn’t know how to deal with the troubled boy. Kemper ran away and tried living with his natural father briefly, but he wasn’t wanted there, either. When he was fifteen, he was sent to live on his paternal grandparents’ remote California ranch.

Things went bad one day in August 1964 while his grandfather, the first Edmund Emil Kemper, was out. The boy was at home with his grandmother when an uncontrollable urge came over him. He shot her in the back of the head, then stabbed her several times. When his grandfather drove up to the house, Kemper decided to spare him the sight of his murdered wife and shot him to death before he ever made it into the house. Alone, Kemper called his mother, then the police. After he was arrested, he explained, “I just wanted to see what it would feel like to shoot Grandma,” and he expressed sorrow that he had missed the opportunity to undress her.

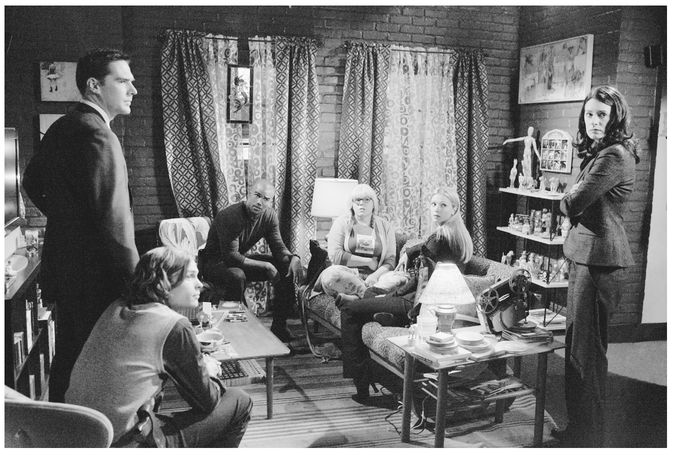

In “Penelope,” Agents Hotchner, Reid, Prentiss, and Jareau gather to help Garcia (center) after she is targeted by a serial killer.

These murders resulted in Kemper being sent to Atascadero State Hospital, a maximum-security facility for the mentally ill. Testing showed him to be a paranoid schizophrenic and to have a near-genius IQ. Kemper hid his inner turmoil and became an assistant to one of the hospital’s psychologists, even administering psychological tests on the doctor’s behalf. What he learned about the testing was to stand him in good stead when it was time for his own examination. After less than five years in the hospital, he was deemed an acceptable risk and released into his mother’s care.

By this time Clarnell had found a job on the campus of the University of California at Santa Cruz. She let Kemper move back in with her. He applied for a job with the California Highway Patrol, but he was too tall. Instead, he found employment with the state highway department and started hanging out at restaurants and bars frequented by cops. He was smart, had a good sense of humor, and could carry on a conversation, so he was accepted by the police officers he met.

The urges Kemper had felt earlier were returning, perhaps heightened by the fact that he was living with his abusive mother again. Finally he saved up enough money to rent a place in Alameda with a friend. During this time, he was building up to the acts that would make him infamous. He went out driving, picking up dozens of female hitchhikers—of which no shortage existed in early 1970s California—and learning how to put them at ease.

The time came to make his fantasies real. On May 7, 1972, Kemper picked up two college girls, Mary Ann Pesce and Anita Luchessa, who were hitchhiking to Stanford University. Kemper tooled around with them for a while, then pulled onto a deserted country road. There he handcuffed Pesce to the seat, locked Luchessa in the trunk, and stabbed them both to death. He hauled them up to Alameda, and in the privacy of his apartment he decapitated Luchessa. He removed Pesce’s clothes and dissected her, cut off her head, and sexually assaulted some of the body parts he had strewn about the room. He dumped the bodies in the mountains, remembering the spot so he could visit later. After keeping both heads for a time, he tossed them into a ravine. He photographed the whole affair with a Polaroid camera.

His fantasy fulfilled for the time being, Kemper kept picking up hitchhikers without harming them—until September 14. On that day he spotted fifteen-year-old Aiko Koo hitchhiking, so he stopped, enticed her into his car, and took her to a rural road. He strangled the girl into unconsciousness and raped her. When she started coming to before he was finished, he strangled her to death and continued. With Koo’s body in his trunk, he paid his mother a visit, then took his “prize” home for dissection. The next day, he had an appointment with a psychiatrist; according to some accounts, while he was inside convincing the doctor that all was well with him, Koo’s head sat in his trunk.

Another four-month stretch passed, during which time Kemper bought a .22 caliber pistol. On January 8, 1973, his victim was Cindy Schall, a hitchhiking college student. He killed her with one shot to the head, then took her to his mother’s house, put her in a closet, and went to bed. In the morning, after his mother left for work, he took the corpse out of the closet, had sex with it, and dissected it, then washed the blood away in the bathtub, placed the pieces in plastic bags, and threw them off a cliff into the ocean. He buried Schall’s head in the yard so that it would be gazing up at his mother’s bedroom window, because, he explained, Clarnell always liked to think people “looked up to her.”

Less than a month went by before Kemper struck again. This time, he went onto the university campus and picked up two separate hitchhikers, Rosalind Thorpe and Alice Liu. Shooting them both on campus, he drove through the guard station at the campus gates with the bodies sitting upright in the car, then moved them into the trunk when he was safely past. At his mother’s house, he decapitated both girls, then carried the heads into his room to sexually assault them.

On March 4, body parts began turning up. Santa Cruz police had recently arrested Herbert Mullin and yet a third Santa Cruz murderer, John Linley Frazier, but when the University of California at Santa Cruz girls disappeared, the authorities knew that a killer still operated in their vicinity. Kemper had kept up his relationship with cops, getting regular reports on how the investigations were proceeding.

Other books

The Last Friend by Tahar Ben Jelloun

The Glass Wall by Clare Curzon

Running With Monsters: A Memoir by Bob Forrest

Flings and Arrows by Debbie Viggiano

The Forgotten War by Howard Sargent

SEX Unlimited: Volume 1 (Unlimited #1) by Kathryn Perez

Daddy's Boy by RoosterandPig

Tales from the Fountain Pen by E. Lynn Hooghiemstra

Fractured (BBW Erotic Romance) by Evelyn Rosado

California Crackdown by Jon Sharpe