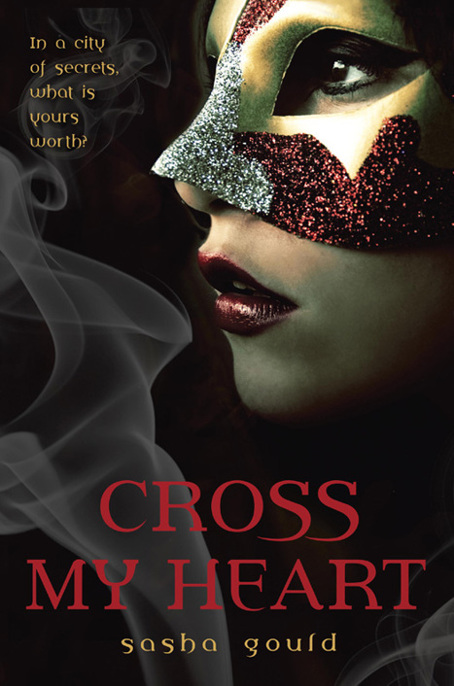

Cross My Heart

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2011 by Working Partners Ltd., London

Jacket art copyright © 2011 Ilona Wellman/Trevillion Images

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in hardcover in the UK by Razorbill, an imprint of the Penguin Group, a division of Penguin Books, Ltd., London, in 2011.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web!

randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools,

visit us at

randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gould, Sasha.

Cross my heart / Sasha Gould.—1st U.S. ed. p. cm.

Summary: When Laura della Scala’s older sister drowns, Laura leaves the shelter of the convent where she has spent the last six years and enters the upper echelons of sixteenth-century Venetian society, while she searches for the truth about what happened to her sister.

eISBN: 978-0-375-98540-9

[1. Secret societies—Fiction. 2. Sex role—Fiction. 3. Love—Fiction. 4. Venice (Italy)—History—16th century—Fiction. 5. Italy—History—16th century—Fiction. 6. Mystery and detective stories.] I. Title.

PZ7.G73585Cr 2012 [Fic]—dc23 2011012357

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

With special thanks to

Sarah Moore Fitzgerald

Contents

Prologue

H

IS GONDOLA SLIPS THROUGH THE WATER

like a knife cutting into dark silk. The two passengers rustle and laugh, but from where he’s standing he can’t really see what they’re up to. It’s none of his concern if some rich old gentleman wants to pay for favors from a young beauty—even if she is some other father’s daughter.

He sighs, pulls his oar against the water and slows to a stop. Wordlessly he helps them both onto the street. For a second he looks straight into the eyes of the man, taking payment, and then the improbable couple sweeps off, the man’s shoes clacking quickly on the stone, the girl’s laughter floating up into the night. Their steps echo down the lane past St. Mark’s Square.

His gondola shines and flashes in the moonlight as he starts to make his way home. He steers it with the skill of generations, gliding by the looming palazzos, slanting and turning past St. Zulian, St. Salvador and Mazzini—along back canals that draw their convoluted chart from

St. Mark’s to the Rialto Bridge. It’s a confusing network, full of false turns and unexpected hazards—easy to get lost, especially at night. Unless you’re a gondolier, in which case you know these watery alleys like the lines on your own face.

He’s close to home when he hears it: a long and awful scream that fills the night. There’s splashing too, and someone bangs a stick on a rail. He rounds a corner and sees an old woman running up and down the bank, begging for help, still wailing. High above, shutters creak open. A voice thick with sleep throatily demands an end to the commotion. Curious faces lean from the frames of weakly lit windows.

At first he thinks that what he sees in the water is a sheet or a curtain—a swollen, soggy dome bobbing gently in the blackness. He drifts closer and sees that it’s a dress that breaks the surface. A woman. Shoeless and facedown. She floats near enough the edge to be pulled to the bank by his oar. With the help of the old woman, he hauls her body onto the stone verge. He’s aware of the people gathering in a ring around them. Slowly, heavily, he turns her over.

It is a girl, perhaps twenty. Soft fingers, now cold. Lips, already blue. In life she must have been exquisite. The eyes are half open, staring limpidly at the sky.

The old woman’s wails become deeper. First she falls beside the body, pulling strands of wet hair from the dead face. Then she stands up and clutches at him with bony hands, wetly clinging to his jacket. “God help me, God help her. Jesus, God in heaven, do something for us!”

He takes the woman’s hands and holds them for a

moment in his. To the onlookers, it could seem like a gesture of comfort or care. But really it’s his effort to disentangle himself from all this panic and grief. “Signora. I’m sorry, Signora, but there’s no helping her now,” he says, and slips away.

N

one of us is known by our real name in here. Almost as soon as you arrive, you’re christened all over again: La Grossa, La Cadavara, La Lunatica, La Trista, La Puera, La Pungenta—Fat, Deathly, Mad, Sad, Fearful and Stinky. Inside the walls of the convent, sneering adjectives are transformed, sooner or later, into names.

They call me La Muta—The Silent One. It isn’t that I don’t have plenty to say, it’s just that most of the time I keep things to myself. Daughters learn this early. Second daughters sooner.

The Abbess used to tell me that she could see something feral in my soul—that there was something of the animal about me. A dog, perhaps, or maybe a rat. The creatures that slip into the convent at night in search of chicken bones and rotting food. It’s something that she’s determined to stamp out.

My life, which once belonged to my father, now belongs to her. I am awake before two for prayers and then again at

five, to go and sing perfect harmonies as the Venetian sun rises behind the grilles and the bars, dancing on the marble and gold in the chapel.

The Abbess controls all the correspondence coming in and going out. Sometimes she withholds the letters from my sister Beatrice and I can’t read them.

Tell me your news

, I beg Beatrice in writing.

When will you marry Vincenzo? Does he make you happy?

None of my questions can be asked without undergoing the prudish scrutiny of the Abbess. To a suspicious mind, alert to all possible evils, any of my words could somehow appear saturated with sin.

“I see everything,” the Abbess tells me. “I know what is in your mind.”

I used to believe her. I used to think that perhaps she really did have the power to see my secret longings leaking like olive oil from the press. Certainly, I’ve seen her holding our letters out in front of her by the corners as if there’s a danger they’ll smear her cowl or habit. As if they’re greasy, grubby things.

Some of Beatrice’s letters reach me. I hide them under a wooden floorboard with my own ring and with a silk-ribboned lock of her hair. Late at night, when Annalena is snoring and shifting under her sheets, I take my sister’s folded ink-filled paper treasures and I read them again and again. Each of her letters carries something from the outside world, smuggling it inside these walls that separate us. Through nothing but an accident of birth, she remains free, while I languish.

Annalena is my

conversa

, my lay sister, my servant nun, and she teases me for smiling in my sleep. She says my eyelids

flutter and she wonders what worlds I’m traveling to in the dark.

In my dreams I’m a child again. Beatrice and I are running down to the Lido for treats from Paulina’s grandmother. Paulina—my friend without a father. It always saddened me that her papa had died when he was young, but now I wonder whether she might actually have been blessed, living as she did, alone with her mother. Her grandmama shrouded her body in black clothes, and the skin on her face was hard and grooved like a walnut.

“The little princesses,” she would call us. And she would lisp,

“Shhh!”

and say “Don’t tell your papa you were here.” And as she looked at our faces she would gasp, “Oh, what husbands you’ll have! What riches! How many men will long to touch your skin and to comb your hair with their fingers!”

She had a bakery, and in the summer, when she couldn’t bear the heat of the ovens, she would let them cool down and make nothing but meringues. She was famous for them. The recipe was known only to her, given to her by her own mother and her mother’s mother before her.

Sospiri di monaca

. That’s what they were called. “The sighs of nuns.” Many recipes share this poignant name, but none have ever tasted like the meringues of Paulina’s grandmother.

On my seventh birthday, Paulina had taken me by the hand and we had run sweating and serious to her grandmother’s bakery, where we both stood silently, looking at the wizened woman. “Grandmama,” she had said eventually. “Laura’s seven years old today.”

“E vero?”

“Yes, it’s true.”

With fingers bent and twisted and brown, like twigs on an old tree, she put seven “sighs” in a little basket and handed it to me. I took a meringue and I bit into it. Brittle at first, and then soft, slowly giving up its flavors of golden sugar from the East, roasted hazelnuts from the South and the zest of Tuscan lemons. I closed my eyes. The sigh that came out of my mouth was hot on my hand.

“Oh, sweetheart!” The old woman grinned. “May all the pleasures in your life be so rapturous and so easy to make.”

In my dreams it’s always summer. My mother is still alive, and she’s smiling. In the six years since I’ve been in the convent, slowly but terrifyingly it’s dawned on me that I’ve forgotten the details of her face. It must be because I’m about to be confirmed. They have set the date. I’m to become a Bride of Christ. The older nuns talk about it like a real wedding. An ethereal groom standing stern beside me, looking at me with neither pride nor with lust, but rather with the arrogance of a father, the stillness of a dead saint. The combined power of Doge and Pope.

I wonder if my sister has kept up her drawing. Perhaps she can send me a picture. She was always the better artist, more methodical; I used to become impatient, losing perspective and spoiling the lines with haste.

Mama. Her misty breath, as sweet as sugared almonds, was warm on my skin. I used to breathe her in, that angel mother of mine. I may not be able to see her face anymore, but I can still smell her: lavender, cinnamon, blossoms of orange and cherry.

My letter is short.

Dear Beatrice

,

Please tell me again what Mama’s face looked like. Send me a sketch, if you can

.

Love from your Laura

There’s nothing for the Abbess to scratch or blot out. I worry that even the absence of something to censor will somehow frustrate and enrage her.

The Abbess allows the letter to be sent. And then I wait.

T

hree days have passed, and still no letter from Beatrice. The only other letters I receive, perhaps four times a year, are from my brother, Lysander, but he’s older than me by ten years—a stranger almost. He lives a scholarly life in Bologna, a place so distant I can’t really imagine it. My father never writes at all.