CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition (15 page)

Read CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition Online

Authors: Eric A. Meyer

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Web / Page Design

Even though you may not

realize it, you're already familiar with font weights; boldfaced text is a very common

example of an increased font weight. CSS gives you more control over weights, at least

in theory, with the propertyfont-weight.

font-weight

- Values:

normal|bold|bolder|lighter|100|200|300|400|500|600|700|800|900|inherit- Initial value:

normal- Applies to:

All elements

- Inherited:

Yes

- Computed value:

One of the numeric values (

100, etc.),

or one of the numeric values plus one of the relative values (bolderorlighter)

Generally speaking, the heavier a font weight becomes, the darker and "more bold" a

font appears. There are a great many ways to label a heavy font face. For example, the

font family known as Zurich has a number of variants, such as Zurich Bold, Zurich Black,

Zurich UltraBlack, Zurich Light, and Zurich Regular. Each of these uses the same basic

font, but each has a different weight.

So let's say that you want to use Zurich for a document, but you'd like to make use

of all those different heaviness levels. You could refer to them directly through thefont-familyproperty, but you really shouldn't

have to do that. Besides, it's no fun having to write a style sheet like this:

h1 {font-family: 'Zurich UltraBlack', sans-serif;}

h2 {font-family: 'Zurich Black', sans-serif;}

h3 {font-family: 'Zurich Bold', sans-serif;}

h4, p {font-family: Zurich, sans-serif;}

small {font-family: 'Zurich Light', sans-serif;}

Aside from the obvious tedium of writing such a style sheet, it works only if

everyone has these fonts installed, and it's a pretty safe bet that most people don't.

It would make far more sense to specify a single font family for the whole document and

then assign different weights to various elements. You can do this, in theory, using the

various values for the propertyfont-weight. This is

a fairly obviousfont-weightdeclaration:

b {font-weight: bold;}

This declaration says, simply, that thebelement

should be displayed using a boldface font; or, to put it another way, a font that is

heavier than the normal font for the document. This is what we're used to, of course,

sincebdoes cause text to be boldfaced.

However, what's really happening is that a heavier variant of the font is used for

displaying abelement. Thus, if you have a paragraph

displayed using Times, and part of it is boldfaced, then there are really two variants

of the same font in use: Times and TimesBold. The regular text is displayed using Times,

and the boldfaced text is displayed using TimesBold.

To understand how a user agent determines the heaviness,

or weight, of a given font variant, not to mention how weight is inherited, it's

easiest to start by talking about the keywords100through900. These number keywords were defined to

map to a relatively common feature of font design in which a font is given nine

levels of weight. OpenType, for example, employs a numeric scale with nine values. If

a font has these weight levels built-in, then the numbers are mapped directly to the

predefined levels, with100as the lightest

variant on the font and900as the heaviest.

In fact, there is no intrinsic weight in these numbers. The CSS specification says

only that each number corresponds to a weight at least as heavy as the number that

precedes it. Thus,100,200,300, and400might all map to the same relatively lightweight

variant;500and600could correspond to the same heavier font variant; and700,800, and900could all produce the same very heavy font

variant. As long as no keyword corresponds to a variant that is lighter than the

variant assigned to the previous keyword, everything will be all right.

As it happens, these numbers are defined to be equivalent to certain common

variant names, not to mention other values forfont-weight.400is defined to be

equivalent tonormal, and700corresponds tobold. The other

numbers do not match up with any other values forfont-weight, but they can correspond to common variant names. If there

is a font variant labeled something such as "Normal," "Regular," "Roman," or "Book,"

then it is assigned to the number400and any

variant with the label "Medium" is assigned to500. However, if a variant labeled "Medium" is the only variant available,

it is

not

assigned to500but

instead to400.

A user agent has to do even more work if there are fewer than nine weights in a

given font family. In this case, it must fill in the gaps in a predetermined way:

If the value

500is unassigned, it is

given the same font weight as that assigned to400.If

300is unassigned, it is given the

next variant lighter than400. If no lighter

variant is available,300is assigned the

same variant as400. In this case, it will

usually be "Normal" or "Medium." This method is also used for200and100.If

600is unassigned, it is given the

next variant darker than that assigned for500. If no darker variant is available,600is assigned the same variant as500. This method is also used for700,800, and900.

To illustrate this weighting scheme more clearly, let's look at three examples of

font weight assignment. In the first example, assume that the font family Karrank% is

an OpenType font, so it has nine weights already defined. In this case, the numbers

are assigned to each level, and the keywordsnormalandboldare assigned to the

numbers400and700, respectively.

In our second example, consider the font family Zurich, which was discussed near

the beginning of this section. Hypothetically, its variants might be assigned numeric

values forfont-weight, as shown in

Table 5-1

.

Table 5-1. Hypothetical weight assignments for a specific font family

Font face | Assigned keyword | Assigned number(s) |

|---|---|---|

Zurich Light | |

|

Zurich Regular |

|

|

Zurich Medium | |

|

Zurich Bold |

|

|

Zurich Black | |

|

Zurich UltraBlack | |

|

The first three number values are assigned to the lightest weight. The "Regular"

face gets the keywordnormal, as expected, and the

number weight400. Since there is a "Medium" font,

it's assigned to the number500. There is nothing

to assign to600, so it's mapped to the "Bold"

font face, which is also the variant to which700andboldare assigned. Finally,800and900are

assigned to the "Black" and "UltraBlack" variants, respectively. Note that this last

assignment would happen only if those faces had the top two weight levels already

assigned. Otherwise, the user agent might ignore them and assign800and900to the

"Bold" face instead, or it might assign them both to one or the other of the "Black"

variants.

Finally, let's consider a stripped-down version of Times. In

Table 5-2

, there are only two weight

variants: "TimesRegular" and "TimesBold."

Table 5-2. Hypothetical weight assignments for "Times"

Font face | Assigned keyword | Assigned numbers |

|---|---|---|

TimesRegular |

|

|

TimesBold |

|

|

The assignment of the keywordsnormalandboldis straightforward enough, of course. As

for the numbers,100through300are assigned to the "Regular" face because there

isn't a lighter face available.400is assigned to

"Regular" as expected, but what about500? It is

assigned to the "Regular" (ornormal) face because

there isn't a "Medium" face available; thus, it is assigned the same font face as400. As for the rest,700goes withboldas always, while800and900,

lacking a heavier face, are assigned to the next-lighter face, which is the "Bold"

font face. Finally,600is assigned to the

next-heavier face, which is, of course, the "Bold" face.

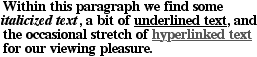

font-weightis inherited, so if you set a

paragraph to bebold:

p.one {font-weight: bold;}

then all of its children will inherit that boldness, as we see in

Figure 5-4

.

Figure 5-4. Inherited font-weight

This isn't unusual, but the situation gets interesting when you use the last two

values we have to discuss:bolderandlighter. In general terms, these keywords have the

effect you'd anticipate: they make text more or less bold compared to its parent's

font weight. First, let's considerbolder.

If you set an element to have a weight ofbolder, then the user agent first must determine whatfont-weightvalue was inherited from the parent

element. It then selects the lowest number, which corresponds to a font weight darker

than what was inherited. If none is available, then the user agent sets the element's

font weight to the next numerical value, unless the value is already900, in which case the weight remains at900. Thus, you might encounter the following situations,

illustrated in

Figure 5-5

:

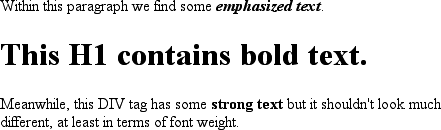

p {font-weight: normal;}

p em {font-weight: bolder;} /* results in bold text, evaluates to '700' */

h1 {font-weight: bold;}

h1 b {font-weight: bolder;} /* if no bolder face exists, evaluates to '800' */

div {font-weight: 100;} /* assume 'Light' face exists; see explanation */

div strong {font-weight: bolder;} /* results in normal text, weight '400' */

Figure 5-5. Text trying to be bolder

In the first example, the user agent moves up the weight ladder fromnormaltobold; in

numeric terms, it jumps from400to700. In the second example,h1text is already set tobold. If

there is no bolder face available, then the user agent sets the weight ofbtext within anh1to800, since that is the next step up from700(the numeric equivalent ofbold). Since800is

assigned to the same font face as700, there is no

visible difference between normalh1text and

boldfacedh1text, but the weights are different

nonetheless.

In the last example, paragraphs are set to be the lightest possible font weight,

which we assume exists as a "Light" variant. Furthermore, the other faces in this

font family are "Regular" and "Bold." Anyemtext

within a paragraph will evaluate tonormalsince

that is the next-heaviest face within the font family. However, what if the only

faces in the font are "Regular" and "Bold"? In that case, the declarations would

evaluate like this:

/* assume only two faces for this example: 'Regular' and 'Bold' */

p {font-weight: 100;} /* looks the same as 'normal' text */

p span {font-weight: bolder;} /* maps to '700' */

As you can see, the weight100is assigned to

thenormalfont face, but the value offont-weightis still100. Thus, anyspantext that is

descended from apelement will inherit the value

of100and then evaluate to the next-heaviest

face, which is the "Bold" face with a numerical weight of700.

Let's take this one step further and add two more rules, plus some markup, to

illustrate how all of this works (see

Figure

5-6

for the results):

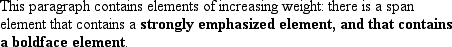

/* assume only two faces for this example: 'Regular' and 'Bold' */

p {font-weight: 100;} /* looks the same as 'normal' text */

p span {font-weight: 400;} /* so does this */

strong {font-weight: bolder;} /* even bolder than its parent */

strong b {font-weight: bolder;} /*bolder still */

This paragraph contains elements of increasing weight: there is a

span element that contains a strongly emphasized

element and a boldface element.

Figure 5-6. Moving up the weight scale

In the last two nested elements, the computed value offont-weightis increased because of the liberal use of the keywordbolder. If you were to replace the text in the

paragraph with numbers representing thefont-weightof each element, you would get the results shown here:

100 400 700 800 .

The first two weight increases are large because they represent jumps from100to400and from400tobold(700). From700, there is no heavier face, so the user agent simply

moves the value offont-weightone notch up the

numeric scale (800). Furthermore, if you were to

insert astrongelement into thebelement, it would come out like this:

100 400 700 800 900

.

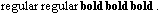

If there were yet anotherbelement inserted

into the innermoststrongelement, its weight

would also be900, sincefont-weightcan never be higher than900. Assuming that there are only two font faces available, then the text

would appear to be either Regular or Bold, as you can see in

Figure 5-7

:

regular regular bold bold

bold .

Figure 5-7. Visual weight, with descriptors