Cyclopedia (40 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

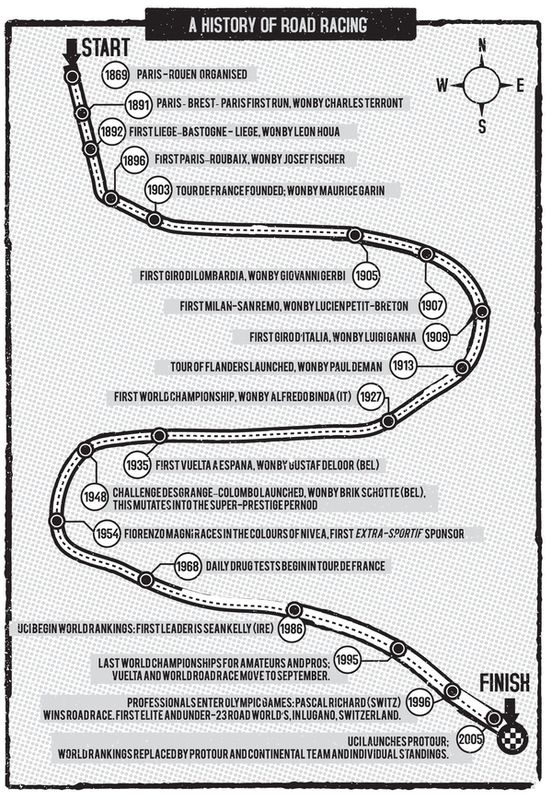

The start list was published on October 20, with 203 names, including six women, three Belgians, and a Germanâand six Britons, including the eventual winner, JAMES MOORE, who took 10 hours 40 minutes for a course later worked out to be 123 kilometers.

Le Vélocipede

's editor Richard Lesclide wrote: “the attitude of the people in the villages along the way was excellent. The velocipedists were greeted with bravos, congratulations and encouragements. Guns were fired as they went through to add to the jollity.”

Le Vélocipede

's editor Richard Lesclide wrote: “the attitude of the people in the villages along the way was excellent. The velocipedists were greeted with bravos, congratulations and encouragements. Guns were fired as they went through to add to the jollity.”

Initially, however, it was in ITALY that racing on the open road gained popularity most rapidly, with a proliferation of events in the early 1870s, including MilanâTurin, first run in 1876 and the oldest major road race still in existence. In Britain, meanwhile, track events were popular, and so too long-distance road events such as the North Road 24-hour TIME TRIAL won by G. P. Mills in the early 1880s, with a distance of 365 km on a HIGH-WHEELER. The fashion for marathon events went back across the Channel to France, where the circulation war between a host of French cycling magazines led to the creation of BordeauxâParis by

Véloce-Sport

magazine in 1891. Mills won that event, thanks to a cunning attack at the main feed station in Angoulême, where his best pacemaker was waiting; he covered the distance in 26 hours

34 minutes, stopping only to “satisfy natural needs.”

Véloce-Sport

magazine in 1891. Mills won that event, thanks to a cunning attack at the main feed station in Angoulême, where his best pacemaker was waiting; he covered the distance in 26 hours

34 minutes, stopping only to “satisfy natural needs.”

Later that year, the first ParisâBrestâParis was run by a rival publication,

Le Petit Journal

âand the HEROIC ERA had begun, with newspapers competing to run longer and harder events; the creation of the TOUR DE FRANCE in 1903 was the logical outcome.

Le Petit Journal

âand the HEROIC ERA had begun, with newspapers competing to run longer and harder events; the creation of the TOUR DE FRANCE in 1903 was the logical outcome.

Early on there was little structure: pacing in the great events was common, be it with tricycles, cars, or just bicyclists carefully selected for their speed, meaning that the best pacemakers were in great demand; without them, it was impossible to win. There were arcane registration procedures to ensure that cyclists started and finished the race on the same bike; for example, early Tour machines were marked in secret by the organizers so the riders couldn't change them. But by the First World War, the main elements of today's road racing season were in place: the five one-day MONUMENTS, the GIRO D'ITALIA and Tour, and a wealth of other CLASSICS and lesser stage races.

The 1930s saw a gradual increase in race speeds as road surfaces improved while team tactics and equipment improved gradually as well, but HENRI DESGRANGE's conservatism held back development in areas such as GEARS.

The years after the Second World War saw rapid changes. The introduction in 1948 of the season-long DesgrangeâColombo prize, awarded for performances across the great races, led to a rapid internationalization of road racing, with the great champions coming out of their home countries more readily, and public support booming. Agents became powerful figures, creaming off percentages from the appearance fees they charged for stars in circuit races and track meetings.

At the same time, with his Bianchi team, FAUSTO COPPI refined team tactics; his squad was highly structured and well equipped, with the star at the center, serviced by

domestiques

â

gregari

in Italianâwho catered to his every need, pushing him early on to save his strength and making the pace to set up the race-winning attack. Finally, Fiorenzo Magni and Raphael Geminiani were the prime movers behind the arrival of

extra-sportif

sponsors to back up the constructors in the 1950s (see TEAMS).

domestiques

â

gregari

in Italianâwho catered to his every need, pushing him early on to save his strength and making the pace to set up the race-winning attack. Finally, Fiorenzo Magni and Raphael Geminiani were the prime movers behind the arrival of

extra-sportif

sponsors to back up the constructors in the 1950s (see TEAMS).

The 1960s saw the system refined with the demise of the independent category, which had provided a stepping stone between the amateur and professional ranks; the beginning of proper drug testing, and the last Tours run under the national team system. The next 30 years were stable, almost backward: professional road racing was largely dominated by riders from the European heartland, sponsors were mainly interested in their own domestic markets, the calendar changed little, and a small number of major stars raced most of the big events taking their teams with them.

That all began to change in the 1980s, as first the English-speaking nations arrived led by the FOREIGN LEGION, followed after the fall of the Berlin Wall by waves of former “amateurs” from EASTERN EUROPE. At the same time, the Tour de France began to dominate the calendar thanks to a massive expansion in television rights and coverage. Sponsors with world interests such as T-Mobile and Panasonic appeared, and the last constructors' teams, RALEIGH and PEUGEOT, went under. Prize money and salaries mushroomed: in 1983 LAURENT FIGNON received £20,000 from his first Tour win, while 16 years later LANCE ARMSTRONG made over $7 million from his first Tour win.

1

1

The sport remains in a state of flux. Since 1998, a series of DRUG scandals have created permanent instability and made a true hierarchy hard to establish as stars are unmasked as cheats. The governing body, the UCI, has tinkered continually

with the professional side of the sport since the inception of the world rankings.

with the professional side of the sport since the inception of the world rankings.

The World Cup was created in 1988 and died a lingering death, Classics were created and died, others lost their value, the calendar was restructured in 1995, while 2005 saw the foundation of the ProTour, splitting pro racing into an elite of ProTeams with feeder systems in each continent to provide a coherent structure. The UCI's three-year feud with ASO led to speculation that the sport might split to form two rival pro calendars. There is still debate over the use of helmet RADIOS.

Thanks primarily to the worldwide impact of LANCE ARMSTRONG, the sport has become globalized. Although the WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS have been devalued by their end-of-season date, and major races in FRANCE, Italy, and SPAIN have disappeared, a wave of new events has emerged, led by the Tour of California and the Tour DownUnder.

Â

Further reading:

A Century of Cycling, the Classic Races and Legendary Champions

, William Fotheringham, Mitchell-Beazley, 2003

A Century of Cycling, the Classic Races and Legendary Champions

, William Fotheringham, Mitchell-Beazley, 2003

ROCHE, Stephen

(b. Ireland, 1959)

(b. Ireland, 1959)

Together with SEAN KELLY, the cherubic Dubliner took Irish cycling to a brief position of world dominance in the 1980s. Roche has a place in cycling history shared only by EDDY MERCKX as a winner of the GIRO D'ITALIA, TOUR DE FRANCE, and world title in a single year. He managed the feat in 1987, taking the Giro after a dramatic attack en route to the Sappada ski station. The victim was his teammate Roberto Visentiniâwho was wearing the pink jerseyâand Roche's “treachery” made him, briefly, a hate figure among the Italian

tifosi.

tifosi.

The Carrera Jeans team was split, with one

domestique

allocated to Roche, the Belgian Eddy Schepers, and the rest working for Visentini. Visentini accused Roche, Schepers, and one of the mechanics, Patrick Valcke, of “holding séances” in their hotel room and said he had bought up all the foreigners in the race to work against him. At one stage finish, Schepers had to threaten Visentini's fans to keep them away from Roche; as the Irishman rode up the mountains the livid

tifosi

spat at him, threw rolled-up newspapers at him, and waved slabs of raw meat under his nose. Roche had the last laugh as he won the raceâwith some help from ROBERT MILLARâand took the Giro and world championship that year.

domestique

allocated to Roche, the Belgian Eddy Schepers, and the rest working for Visentini. Visentini accused Roche, Schepers, and one of the mechanics, Patrick Valcke, of “holding séances” in their hotel room and said he had bought up all the foreigners in the race to work against him. At one stage finish, Schepers had to threaten Visentini's fans to keep them away from Roche; as the Irishman rode up the mountains the livid

tifosi

spat at him, threw rolled-up newspapers at him, and waved slabs of raw meat under his nose. Roche had the last laugh as he won the raceâwith some help from ROBERT MILLARâand took the Giro and world championship that year.

The Tour followed, after a race-long battle with Pedro Delgado that included an episode at La Plagne in the ALPS where he blacked out briefly after the finish. Roche eventually took the yellow jersey from Delgado on the penultimate day to win by just 40 seconds. That year's world title in Villach, Austria, looked destined for Kelly, but it was Roche who attacked a late break to win.

However, his career went downhill from there, in a classic case of the CURSE of the rainbow jersey. He barely raced as world champion following a serious knee injury and operation, pulled out of the 1989 Tour, and was bizarrely eliminated from the 1991 race after his team started without him in a team time trial stage. He achieved one more major win, a stage in the 1992 Tour, before retirement in 1993. He now runs a hotel in the south of France. Both his son Nicolas and his nephew Daniel Martin are successful professional cyclists.

ROUGH STUFF

Cycling off-road using road bikes that are often adapted with fatter tires and cyclo-cross brakes. In Britain rough-stuff routes include green lanes, old Roman roads, and roughly surfaced bridleways, while in Scotland the network of military roads built by General Wade is used. Rough Stuff predates the invention of the MOUNTAIN BIKE by many years, dating back to the late 19th century.

Cycling off-road using road bikes that are often adapted with fatter tires and cyclo-cross brakes. In Britain rough-stuff routes include green lanes, old Roman roads, and roughly surfaced bridleways, while in Scotland the network of military roads built by General Wade is used. Rough Stuff predates the invention of the MOUNTAIN BIKE by many years, dating back to the late 19th century.

The Rough Stuff Fellowship publishes ride details and a newsletter.

Â

(SEE

CYCLO-CROSS

AND

MOUNTAIN-BIKING

FOR OTHER WAYS OF GETTING AWAY FROM ASPHALT)

CYCLO-CROSS

AND

MOUNTAIN-BIKING

FOR OTHER WAYS OF GETTING AWAY FROM ASPHALT)

S

SADDLES

From the late 19th century until the 1970s, most saddles were made the same way: from a teardrop-shaped leather strip strung on a metal frame. Now, however, the principal volume producer of leather saddles is the British firm Brooks, and most models are a hybrid of plastic or carbon-fiber base, foam or gel padding, with a slim covering of either fine leather or synthetic fiber. The center of the cycle saddle industry is in the Veneto region of Northern Italy, home to Selle Royal, Selle Italia, and Selle San Marco.

From the late 19th century until the 1970s, most saddles were made the same way: from a teardrop-shaped leather strip strung on a metal frame. Now, however, the principal volume producer of leather saddles is the British firm Brooks, and most models are a hybrid of plastic or carbon-fiber base, foam or gel padding, with a slim covering of either fine leather or synthetic fiber. The center of the cycle saddle industry is in the Veneto region of Northern Italy, home to Selle Royal, Selle Italia, and Selle San Marco.

Leather saddles such as the iconic Brooks B17 look distinguished but are heavier than composite ones and sag if they get wet; they also have to be “broken-in,” a process in which they are ridden for several hundred miles until their shape matches that of the rider's behind. While this is going on they have to be dressed with some kind of oil such as neatsfoot, seal oil, or in extreme cases motor oil. Some aficionados go so far as to soak them in oil. Not everyone goes as far as TOM SIMPSON, who made his own saddle using a plastic sports saddle, some foam, and his wife's handbag; mostly, cyclists find a ready-made one which suits and stick with it.

SADDLE SORES

A perennial issue, but less common today. Professional cyclists of the HEROIC ERA suffered almost constantly from saddle boils, when the skin of the crotch becomes abraded, enabling dirt from the road to get in and infection to develop. In the 1950s and 1960s, the TOUR DE FRANCE doctor Pierre Dumas describes seeing riders with a massive swelling in the perineum nicknamed the “third testicle.” LOUISON BOBET's career was cut short after he heroically rode on with a saddle boil to win the 1955 Tour, and an uncomfortable sore probably contributed to LAURENT FIGNON's narrow defeat in the 1989 Tour.

A perennial issue, but less common today. Professional cyclists of the HEROIC ERA suffered almost constantly from saddle boils, when the skin of the crotch becomes abraded, enabling dirt from the road to get in and infection to develop. In the 1950s and 1960s, the TOUR DE FRANCE doctor Pierre Dumas describes seeing riders with a massive swelling in the perineum nicknamed the “third testicle.” LOUISON BOBET's career was cut short after he heroically rode on with a saddle boil to win the 1955 Tour, and an uncomfortable sore probably contributed to LAURENT FIGNON's narrow defeat in the 1989 Tour.

Geoffrey Nicholson, in

The Great Bike Race

, recalled the 1976 Tour runner-up Joop Zoetemelk pulling down his shorts to show journalists a boil “the size of an egg” on his inner thigh to explain why he wasn't able to challenge the winner Lucien Van Impe. LANCE ARMSTRONG's teammate Frankie Andreu finished one Tour with a vast hole cut in his saddle to accommodate a sore.

The Great Bike Race

, recalled the 1976 Tour runner-up Joop Zoetemelk pulling down his shorts to show journalists a boil “the size of an egg” on his inner thigh to explain why he wasn't able to challenge the winner Lucien Van Impe. LANCE ARMSTRONG's teammate Frankie Andreu finished one Tour with a vast hole cut in his saddle to accommodate a sore.

Some cyclists swear by the use of cream on the insert in their shorts, others prefer to pedal dry; none now resort to the 1930s remedy of putting a raw steak down below. All are agreed, however, that nothing apart from a little cream should come between a cyclist and his insert, once made of soft chamois leather (which would harden uncomfortably with washing and had to be treated before use), now more likely to be an artificial padded fabric. Repeated cycling seems to harden the skin in the crotch for male cyclists, who should not have to resort to the remedies recommended by TOM SIMPSON: ice water baths or cocaine lotions to deaden the nerves.

Â

SAFETY BICYCLES

A type of bike born of a spate of inventions in the 1870s and 1880s as designers attempted to improve on the HIGH-WHEELER by making the bike more stable and introducing rear-wheel drive. The definitive safety bicycle was produced in 1885 with the launch of the Rover designed by JAMES STARLEY.

A type of bike born of a spate of inventions in the 1870s and 1880s as designers attempted to improve on the HIGH-WHEELER by making the bike more stable and introducing rear-wheel drive. The definitive safety bicycle was produced in 1885 with the launch of the Rover designed by JAMES STARLEY.

Starley's third model for the Rover had the diamond frame, rear chain driveâthe bush-roller chain as we know it today had been invented in 1880âand direct front-wheel steering that now define most bikes. The size of the Rover could be altered for cyclists of various heights; the gears were also changeable by varying the size of chain rings and sprockets. An 1869 machine made by Frenchmen Meyer and Guilmet had included similar features but had never been marketed due to the Franco-Prussian war.

The only issue with safety-type bicycles was that the smaller wheels were less forgiving than the larger ones used on the high-wheeler, but that was solved in 1888 when John Boyd Dunlop, a vet in Belfast, patented the pneumatic tire (see TIRES for the development of this vital item). Initially the tires were glued and bound to the wheel-rim but later in the decade Michelin of France patented a wired-on tire.

Fundamentally, the modern bicycle was born. What remained was perfecting the various areas: the development of gearing, lighter and stronger components, mass production to drive down prices and make the machines ever more popular. Key developments in WHEELS, FRAMES (materials and design), BRAKES, tires, and GEARS are covered in their individual sections.

SCHUERMANN, Clemens

(b. 1888, d. 1957),

Herbert

(b. 1925, d. 1994), and

Ralph

(b. 1953)

(b. 1888, d. 1957),

Herbert

(b. 1925, d. 1994), and

Ralph

(b. 1953)

The German family of architects who between them have built many of the world's velodromes: 122 at the last count, including the Olympic tracks in Beijing, Barcelona, Seoul, Mexico City, and Rome; the Hamar track in Norway; the Meadowbank velodrome in Edinburgh; the UCI's World Cycling Center track in l'Aigle, Switzerland; and the Vigorelli velodrome in Milan.

Clemens Schuermann was a track cyclist who invented an early cycling helmet and later became an architect who began constructing velodromes in 1926. He experimented with velodrome construction with a temporary track in his home town of Muenster, which he built and rebuilt each year, continually altering the transitionsâthe point where the rider exits the banking and enters the straight. He discovered that at this point, centrifugal forces mean a properly designed track can guide the rider around the curve so that he or she does not have to turn the handlebars.

The Vigorelli was Clemens's masterpiece; his son Herbert continued the tradition, working

around the globe on 55 tracks and helping the UCI with track design, reducing standard length to 250 m. He handed the business down in turn to his son Ralph, who designed the velodrome at Hamar, Norway, in a radically shaped building resembling a Viking longship, and, most recently, the futuristic track used at the Beijing OLYMPIC GAMES.

around the globe on 55 tracks and helping the UCI with track design, reducing standard length to 250 m. He handed the business down in turn to his son Ralph, who designed the velodrome at Hamar, Norway, in a radically shaped building resembling a Viking longship, and, most recently, the futuristic track used at the Beijing OLYMPIC GAMES.

Â

(SEE ALSO

HOUR RECORD

,

TRACK RACING

)

HOUR RECORD

,

TRACK RACING

)

SCHWINN

America's best-known cycle maker, which was founded in Chicago by two German émigrés, Ignaz Schwinn and Adolph Arnold, started production in 1895 and was responsible for two classic designs. Under Ignaz's son Frank W. Schwinn, the Aerocycle was based on motorcycle design with 2.125-inch balloon tiresâspecially produced by the American Rubber Company at Schwinn's requestâvast mudguards, a chrome-plated headlight, and push-button bell. It was later known as the cruiser. The Stingray of 1963, designed by Al Fritz, was another motorcycle-based design. Fritz was inspired by a Californian youth trend for fitting bikes with motorbike parts, and produced a machine that featured high-rise handlebars known as apehangers, a banana-shaped seat, and 20-inch wheels, which was adapted by RALEIGH and marketed successfully in the UK as the Chopper.

America's best-known cycle maker, which was founded in Chicago by two German émigrés, Ignaz Schwinn and Adolph Arnold, started production in 1895 and was responsible for two classic designs. Under Ignaz's son Frank W. Schwinn, the Aerocycle was based on motorcycle design with 2.125-inch balloon tiresâspecially produced by the American Rubber Company at Schwinn's requestâvast mudguards, a chrome-plated headlight, and push-button bell. It was later known as the cruiser. The Stingray of 1963, designed by Al Fritz, was another motorcycle-based design. Fritz was inspired by a Californian youth trend for fitting bikes with motorbike parts, and produced a machine that featured high-rise handlebars known as apehangers, a banana-shaped seat, and 20-inch wheels, which was adapted by RALEIGH and marketed successfully in the UK as the Chopper.

Schwinn's Paramount was its most successful road bike brand, introduced in 1938 under Frank W. Schwinn and made in low numbers in a small unit that was separate from the main factory, but after that the company never seemed truly at ease with road bike manufacturing, possibly because it never sponsored a team that raced in the European hotbed. The Paramount was updated in the 1950s with Reynolds tubing, and the multi-geared Varsity and Continental

brands sold well in the 1960s. But Schwinn missed out on the surge in road racing interest in the US in the 1970s: the bikes they offered were not light or responsive enough compared to what was offered from Europe. Similarly the company failed to truly capitalize on the later BMX and MOUNTAIN-BIKE boomsâalthough ironically enough the Schwinn cruisers were an inspiration for the earliest mountain bikes, and Schwinn briefly produced a mountain bike named the Klunker 5. Schwinn outsourced manufacturing to GIANT, which launched its own brands and overtook it in the late 1980s. The name has been bought, sold, and relaunched over the last 15 years. In 1993, during one difficult spell, Richard Schwinn, great-grandson of Ignaz Schwinn, founded Waterford Precision Cycles, an offshoot based in the former Paramount production plant in Waterford, Wisconsin, which makes lightweight machines in limited numbers.

brands sold well in the 1960s. But Schwinn missed out on the surge in road racing interest in the US in the 1970s: the bikes they offered were not light or responsive enough compared to what was offered from Europe. Similarly the company failed to truly capitalize on the later BMX and MOUNTAIN-BIKE boomsâalthough ironically enough the Schwinn cruisers were an inspiration for the earliest mountain bikes, and Schwinn briefly produced a mountain bike named the Klunker 5. Schwinn outsourced manufacturing to GIANT, which launched its own brands and overtook it in the late 1980s. The name has been bought, sold, and relaunched over the last 15 years. In 1993, during one difficult spell, Richard Schwinn, great-grandson of Ignaz Schwinn, founded Waterford Precision Cycles, an offshoot based in the former Paramount production plant in Waterford, Wisconsin, which makes lightweight machines in limited numbers.

Other books

The Secret She Kept by Amy Knupp

Chosen by Lisa Mears

The Pelican Bride by Beth White

Kings Pinnacle by Robert Gourley

The Breath of Suspension by Jablokov, Alexander

We're All in This Together by Owen King

Zack (In the Company of Snipers Book 3) by Irish Winters

Pieces of it All by Tracy Krimmer

Anita Mills by Newmarket Match

Ctrl Z by Stone, Danika