Cyclopedia (46 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

Â

TIRES

Pioneered by John Boyd Dunlop, who wanted to improve his son's tricycle. He used a “sausage” on the wheel rim, which was first a water-filled hosepipe, then a tube of rubber wrapped in canvas. Dunlop then put on a rubber tread and a one-way valve that only let air in, not out, and patented the design in 1888. Initially there was scepticism, but in May 1889 his tires were tested in competition in Belfast by W. Hume, who won four events out of four.

Pioneered by John Boyd Dunlop, who wanted to improve his son's tricycle. He used a “sausage” on the wheel rim, which was first a water-filled hosepipe, then a tube of rubber wrapped in canvas. Dunlop then put on a rubber tread and a one-way valve that only let air in, not out, and patented the design in 1888. Initially there was scepticism, but in May 1889 his tires were tested in competition in Belfast by W. Hume, who won four events out of four.

Also in the 1880s, another household name, Hutchinson, began making tires at their factory in France.

In about 1887 the concentric bead principle or “clincher” that held the tire on to the rim was patented by A. C. Welch. Dunlop bought the patent in 1892. This was to be the basis of their fortune, being the only practical way to make a clincher tire that could be easily detached from the rim to enable punctures to be repaired.

In 1892, Michelin ran a race from Paris to their base in Clermont-Ferrand, open only to riders using pneumatic tires; they arranged for 25 kg of nails to be scattered on the road, to demonstrate how good their products were. Ironically the first finisher, Auguste Stéphane, was using Dunlops; he was disqualified.

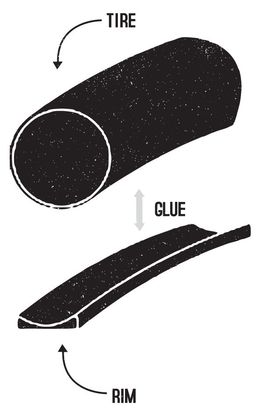

Tires divide into conventional high-pressures, in essence a refinement of the 1890s Michelin design, and tubulars or “sew-ups,” in which the inner tube is held inside a cylindrical casing made by sewing both sides of the carcass together. Tubulars were

the racer's choice for a century after the Wolber company offered a prize for the first Tourman to finish on its “removable” tire; the Tourman with a spare or two strung round his neck epitomized the HEROIC ERA. The only downside was the fact that they had to be glued securely onto the rim, meaning that the casing had to be unstitched if the inner tube needed repair. Once restitched after repair, a “tub” was never quite the same again.

the racer's choice for a century after the Wolber company offered a prize for the first Tourman to finish on its “removable” tire; the Tourman with a spare or two strung round his neck epitomized the HEROIC ERA. The only downside was the fact that they had to be glued securely onto the rim, meaning that the casing had to be unstitched if the inner tube needed repair. Once restitched after repair, a “tub” was never quite the same again.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Michelin began producing the first high-performance “clincher” tires with a narrower, lighter casing and a flexible bead so the tire could be folded, and since then clincher performance has improved virtually year on year, to the extent that now the difference between high-grade clincher and medium-weight tubular is a matter of tiny degree: the best tubulars offer about a 50 g saving, which is significant in high-performance terms, but their cost and the risk of puncturing makes them second choice for most road racers.

Tubulars remain the first-choice for velodrome racing, however, because punctures are less likely, and for safety reasons: they should not come off the rim in the event of a puncture. Sticking them on remains an art, however: the new rim has to be abraded to give the glue purchase, and then it has to be given several coats. Top tubular makers include Vittoria of Italy, and Clément of France, while generations of CYCLO-CROSS riders swore by

custom-made studded fat “tubs” from Parisian firm Dugast. Aficionados emulate top racers such as EDDY MERCKX and keep tubulars for years in dark places to season them like fine wine, and pro-team service courses sometimes have a locked tubular room in whichâthe Motorola mechanics used to claim in the early 1990sâthe head wrench-man can go and savor the rubber and glue fumes.

custom-made studded fat “tubs” from Parisian firm Dugast. Aficionados emulate top racers such as EDDY MERCKX and keep tubulars for years in dark places to season them like fine wine, and pro-team service courses sometimes have a locked tubular room in whichâthe Motorola mechanics used to claim in the early 1990sâthe head wrench-man can go and savor the rubber and glue fumes.

Tire covers have been made of various materials including hemp and nylon, while silk-woven tubular tires were once the ultimate choice for track racing, with heavier cottons used for training and road racing. The bullet-proof fiber kevlar is a recent development but is now common to most high-end tires to give an extra puncture-proof edge.

Punctures were once the cyclist's bane. Generations have sought remedies for this thorny problem, including thin tape underneath high-pressure covers, foam injected tires, semi-solid tires made up of multiple rubber balls and a pump (the Skinner Automatic) located inside the wheel that made a single pedal stroke with every revolution of the wheel. The modern generation of tires makes riding generally flat-free.

Tire-savers were popular for many years: lightly sprung strips of wire with a plastic strip on them that would be fixed to the brake bolts so they brushed the surface of the tire, to whip off any thorns or flints before they were pushed through the cover. (They had one nasty side-effect, which was to spray water all over the rider in the wet.) Few cyclists, however have gone as far as the British Tour de France star ROBERT MILLAR, who in winter would put a tubular tire inside a high-pressure cover in place of the inner-tube.

TOULOUSE-LAUTREC, Henri de

(b. France, 1864, d. 1901)

(b. France, 1864, d. 1901)

The French impressionist was an illustrator of early cycling in Paris, a racing fan who went regularly to the Buffalo and Seine velodromes through his friendship with the track's technical director Tristan Bernard. The results, wrote Bernard, did not interest the artist, but the atmosphere and the people did. Toulouse-Lautrec's poster for the Simpson chain company,

La Chaîne Simpson

, is an iconic example of the genre (see POSTERS for others; ART for what draws artists to cycling).

La Chaîne Simpson

, is an iconic example of the genre (see POSTERS for others; ART for what draws artists to cycling).

The version seen most often depicts the French champion Constant Huret, watched by the raffish Bernard and the French importer who gave himself the English name Spoke. It shows one of what became known as the Chain Matches from 1896, when the Simpson company pitted top cyclists of the time such as the Welsh stars Jimmy Michael and Arthur Linton against all-comers to publicize the product. Toulouse-Lautrec traveled with the team from Paris to London to attend the matches.

This is actually Toulouse-Lautrec's second attempt. The first, showing Michael trainingâcomplete with his trademark toothpick in his mouthâwas rejected because the chain company was not happy with the artist's depiction of the triangular links. Intriguingly, the picture also shows the

soigneur

Choppy Warburton looking for somethingâa pick-me-up presumablyâin a Gladstone bag (see SOIGNEURS for more on these witchdoctors and their magic remedies).

soigneur

Choppy Warburton looking for somethingâa pick-me-up presumablyâin a Gladstone bag (see SOIGNEURS for more on these witchdoctors and their magic remedies).

The artist also drew his friend, the singer Aristide Bruant, on his bike and produced a notable lithograph of the American sprinter A. A. ZIMMERMAN (

Zimmerman et Sa Machine

) to go with a magazine article written by Bernard.

Zimmerman et Sa Machine

) to go with a magazine article written by Bernard.

TOUR DE FRANCE

After the finish of the first Tour de France in 1903, the winner MAURICE GARIN gave the organizer HENRI DESGRANGE a handwritten account of the race to be printed in Desgrange's newspaper

L'Auto

. “You have revolutionised the sport of cycling,” he wrote, “and the Tour de France will remain a key date in the history of road racing.” His words still I ring true. Approaching its 110th birthday, the Tour is cycling's flagship race, the only event in the racing calendar that has significance in every country, and the biggest annual sports event in the world.

After the finish of the first Tour de France in 1903, the winner MAURICE GARIN gave the organizer HENRI DESGRANGE a handwritten account of the race to be printed in Desgrange's newspaper

L'Auto

. “You have revolutionised the sport of cycling,” he wrote, “and the Tour de France will remain a key date in the history of road racing.” His words still I ring true. Approaching its 110th birthday, the Tour is cycling's flagship race, the only event in the racing calendar that has significance in every country, and the biggest annual sports event in the world.

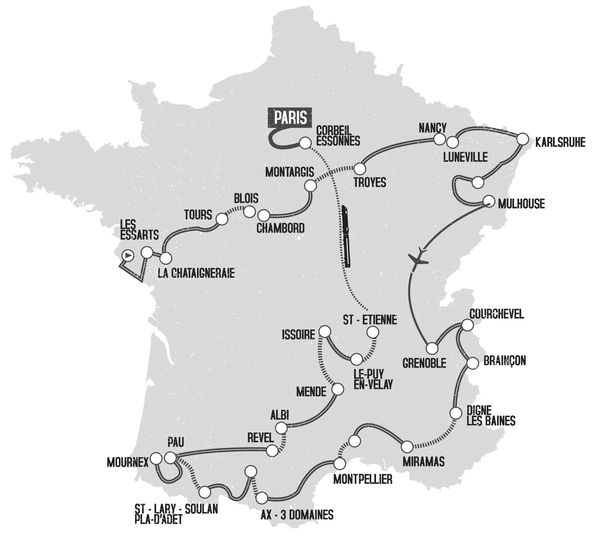

The Tour's enduring fascination lies in the fact that its core principles have not changed. It began life as an outlandish, mammoth publicity stunt, and still is. It still circumnavigates France on public roads and remains free for the public to watch. Unlike every other great sports event in the world, it goes out to its public rather than being confined to a stadium. People travel to watch the race, but virtually every village in France has been visited at some point. As the late Geoffrey Nicholson wrote, it is the only form of international conflict that takes place on the doorstep other than war itself. It is also now an integral part of the French summer, “the fete of all our countryside” as the writer Louis Aragon put it.

The man who dreamed up the Tour was Géo Lefèvre, rugby and cycling writer at

L 'Auto

, but the editor Desgrange coined the name. At a meeting to discuss ways to boost circulation, which was flagging, Lefèvre suggested “a race that lasts several days, longer than anything else. Like the SIX-DAYS on the track but on the road.” Desgrange answered “If I understand you right,

petit

Géo, you're proposing a Tour de France?” The term was not a new one: the

Compagnons du Tour de France

were apprentice craftsmen who took three years to go around the country. France had been circumnavigated several times by bike and the French daily

Le Matin

had run a Tour de France car race in 1899.

L 'Auto

, but the editor Desgrange coined the name. At a meeting to discuss ways to boost circulation, which was flagging, Lefèvre suggested “a race that lasts several days, longer than anything else. Like the SIX-DAYS on the track but on the road.” Desgrange answered “If I understand you right,

petit

Géo, you're proposing a Tour de France?” The term was not a new one: the

Compagnons du Tour de France

were apprentice craftsmen who took three years to go around the country. France had been circumnavigated several times by bike and the French daily

Le Matin

had run a Tour de France car race in 1899.

Tour Records

=

Â

Most overall wins:

Lance Armstrong (US) 1999â2005, 7

Lance Armstrong (US) 1999â2005, 7

Â

Most green jersey wins:

Erik Zabel (Ger) 1996â2001, 6

Erik Zabel (Ger) 1996â2001, 6

Â

Most King of Mountains wins:

Richard Virenque (Fra), 6

Richard Virenque (Fra), 6

Â

Most stage wins:

Eddy Merckx (Bel), 35

Eddy Merckx (Bel), 35

Â

Most stage wins in one Tour:

8: Merckx 1970, 1974; Charles Pelissier (Fr) 1930; Freddy Maertens (Bel) 1976

8: Merckx 1970, 1974; Charles Pelissier (Fr) 1930; Freddy Maertens (Bel) 1976

Â

Youngest winner:

Henri Cornet (Fr) 1904, 20

Henri Cornet (Fr) 1904, 20

Â

Oldest winner:

Firmin Lambot (Bel) 1922, 35

Firmin Lambot (Bel) 1922, 35

Â

Most Tours ridden and finished:

Joop Zoetemelk (Hol) 16â1970â3; 1975â86

Joop Zoetemelk (Hol) 16â1970â3; 1975â86

Â

Smallest winning margin:

Greg LeMond (US), 1989, 8 seconds

Greg LeMond (US), 1989, 8 seconds

Â

Largest postwar winning margin:

Fausto Coppi (Ita), 1952, 28 minutes 17 seconds

Fausto Coppi (Ita), 1952, 28 minutes 17 seconds

The race was announced in the paper on January 19, 1903; the plan was for an event that would take 35 days, but after protests from the professional cyclists who would make up the field this was amended to a six-stage event taking 19 days. Initially there was little interest from professional cyclists: Desgrange upped the prize money, halved the entry fee, and allocated five francs expenses per day. There were 78 entries.

Desgrange was not confident of the race's success and stayed away from the first Tour when it began on July 1, 1903, at the Réveil-Matin Café in the Paris suburb of Montgéron (the first road stage of the centenary Tour of 2003 began from the Réveil-Matin, still in situ but now a Wild West themed restaurant).

It was Lefèvre who followed the race from start to finish, traveling by train and bike, and providing a page of reports every day. His son described his role like this: “lost all alone in the night, he would stand on the edge of the road, a storm lantern in his hand, searching the shadows for riders who surged out of the dark from time to time, yelled their name and disappeared into the distance. He alone was the âorganisation' of the Tour de France.”

The early Tours were marred by cheating: in the first race won by Maurice Garin several riders were thrown out, and in the second, Garin and the next three riders overall were disqualified (for more details, see GARIN). The winner was the man placed fifth, Henri Cornet, who at 20 remains the Tour's youngest winner. It was estimated, however, that 125 kg of tacks were strewn on the route the following year, and the same thing happened in 1906, when only 14 riders finished.

Tour Landmarks

=

| 1903â | first Tour won by Maurice Garin |

| 1910â | race passes through Pyrenées for first time |

| 1911â | the race goes over Col du Galibier in the Alps |

| 1919â | first yellow jersey, worn by Eugène Christophe |

| 1920â | Philippe Thys is first man to win the Tour three times |

| 1930â | publicity caravan appears |

| 1933â | first King of the Mountains prize awarded to Vicente Trueba (Spain) |

| 1937â | derailleur GEARS permitted |

| 1947â | first stage finish outside France (Brussels) |

| 1949â | Fausto Coppi is first man to win Tour and Giro in same year |

| 1950â | elimination for finishing outside stage time limit brought in |

| 1952â | first mountain top stage finish: l'Alpe d'Huez |

| 1953â | green jersey for points prize introduced, won by Fritz Schaer (Switz) |

| 1954â | first Tour start outside France, Amsterdam |

| 1964â | JACQUES ANQUETIL is first man to win the Tour five times |

| 1967â | first time-trial prologue |

| 1968â | regular drug tests introduced, last Tour contested by national teams |

| 1971â | first air transfer between stages |

| 1974â | first cross-Channel transfer for stage in Plymouth |

| 1975â | Tour finishes on Champs-Elysées for first time |

| 1983â | Tour goes “open,” including Colombian amateurs |

| 1984â | women's Tour de France begins, won by Marianne Martin (US); it ends in 1989 |

| 1995â | MIGUEL INDURAIN is first man to win Tour five times in a row |

| 1998â | Festina doping scandal |

| 2005â | Lance Armstrong takes seventh win in a row |

The Tours of the HEROIC ERA were slogs that called for superhuman levels of willpower and endurance, along appalling roads that made massive demands on poorly built bikes. In the first Tour, some participants took up to 35 hours to complete the stages. There were countless episodes in which cyclists broke frames or wheels and had to carry out roadside repairs; most celebrated is the episode in 1913 when Eugène Christophe broke his forks and had to repair them in a blacksmith's.

Early on, the Tour flirted with various formats. Initially there was a rest day after each stage, and it was decided on points from 1906 to 1911. Later, team time trials became a main feature as Desgrange tried to prevent the riders forming alliances on the road. But it gradually moved to a format similar to that of today's race: daily stages with the occasional rest day. Desgrange took the race outside France's borders in 1905, when it visited Alsace-Lorraine. He held time trials, both individual and for teams. There have been modifications, but only relatively minor ones.

The biggest innovation came in 1910, when the race was taken into the PYRENÃES. The move was proposed to Desgrange by his assistant, Alphonse Steinès, who reconnoitred the Col du Tourmalet in January, when it was blocked by snow. He walked over the pass and telegrammed his boss to say the road was perfectly usable, although he had barely seen it. The Tour's first major mountain stage, from Luchon to Bayonne, included the four legendary passes of the Peyresourde, Aspin, Tourmalet, and Aubisque. As he pushed his bike up the Aubisque, the eventual race winner Octave

Lapize looked at Lefèvre and companyâDesgrange was absentâand spat out the word “assassins.” The ALPS were included in the route a year later. On the Col du Galibier, that year's winner Gustave Garrigou shoved his bike through massive snowdrifts on a road that was little more than a mud track.

Lapize looked at Lefèvre and companyâDesgrange was absentâand spat out the word “assassins.” The ALPS were included in the route a year later. On the Col du Galibier, that year's winner Gustave Garrigou shoved his bike through massive snowdrifts on a road that was little more than a mud track.

For many years, the Tour's appeal lay in the fact that the public could relate to the effort involved in bike racing, as pretty much everyone could ride a bike. They could admire the Tourmen's ability to achieve feats beyond mere mortals, be it winning a sprint at 50 kph, climbing a mountain, or whizzing downhill at 100 kph: “industry mixed with heroism” as Aragon put it.

Today, that has changed a little. Few people ride bikes to work any more, but cycling enthusiasts can ride the race's great mountains in any number of leisure events, and many ride up and down before the race comes. It's rare in any sport for spectators to be able to emulate their heroes in this way. The inception of the ÃTAPE DU TOUR in 1993 enabled ordinary mortals to ride one leg of the race under the same conditions as the Tourmen, assuming they were fit enough, and led to a huge increase in semi-competitive endurance events.

The Tour is more than a mere sports event. Fans of GINO BARTALI claim that his 1948 win saved Italy from revolution. Desgrange believed that the sacrifice embodied by the Tour riders could serve as a moral example, and Jean-Marie Leblanc, who ran the race from 1989 to 2004, believed the event had a social mission: bringing good cheer to forsaken parts of France. It was under Leblanc that the race began traveling to the center of the country rather than keeping to the periphery.

Other books

Brechalon by Wesley Allison

The Full Cleveland by Terry Reed

More Than Chains To Bind by Stevie Woods

Rough Edges by Kimberly Krey

The Samurai's Garden: A Novel by Tsukiyama, Gail

Reunion at Cardwell Ranch by B.J. Daniels

Halfway to the Grave by Jeaniene Frost

Rock with Wings by Anne Hillerman

The County of Birches by Judith Kalman