Cyclopedia (50 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

VERBRUGGEN, Hein

(b. Netherlands, 1941)

(b. Netherlands, 1941)

A combative, articulate Dutchman who ran the UNION CYCLISTE INTERNATIONAL from 1991 to 2005, introducing a number of innovations to cyclingâsome successful, some less soâbefore moving on to become a prominent figure in the Olympic movement.

Verbruggen began his cycling career in marketing, working for the Mars chocolate bar company when they sponsored a professional team in the early 1970s. By 1990 he had risen up the hierarchy of cycling to head the professional arm of the sport, the FICP, and in 1991 he became UCI president.

Under Verbruggen professional world rankings were brought in along the lines of the ATP ranking in tennisâthese were actually invented by the French cycling magazine

Vélo

âa yearlong World Cup was inaugurated and attempts were made to export cycling beyond its European heartland, with major events in Canada and the UK. The UCI was moved to its present base in Aigle, Switzerland, and a world cycling center set up, including a velodrome designed by the SCHUERMANN family. Moves were made to bring in nations such as AFRICA.

Vélo

âa yearlong World Cup was inaugurated and attempts were made to export cycling beyond its European heartland, with major events in Canada and the UK. The UCI was moved to its present base in Aigle, Switzerland, and a world cycling center set up, including a velodrome designed by the SCHUERMANN family. Moves were made to bring in nations such as AFRICA.

The cycling calendar was radically altered, with the VUELTA A ESPAÃA moving from April to September and the WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP from August to September. The Vuelta has never seemed to work so late in the year and the World Cup concept did not take off as the TOUR DE FRANCE came to dominate the cycling season in the 1990s. Once Perrier pulled out, the event never found a sponsor and was eventually dropped.

In 1996 Verbruggen achieved his masterstroke, gaining professionals access to the OLYMPIC GAMES. To enable that, the sport had to be brought under one banner. The amateur and professional categories were abolished and replaced by Elite and Under-23. Under Verbruggen both MOUNTAIN-BIKING and BMX were brought into the Olympics, but there was controversy when the long-established kilometer time trial was dropped.

The DRUGS problem became increasingly high-profile in the 1990s and in an attempt to limit the use of EPO, the UCI under Verbruggen brought in blood testing in 1997, initially to monitor professional cyclists' health. The tests were counterproductive, actually encouraging the use of EPO within a certain limit, but they paved the way for more radical blood profiling as well as tests for blood transfusions.

When Verbruggen moved on in 2005, his final initiative was to devise the ProTour structure, which guaranteed entry to major races for teams who paid a registration fee to the PTârun by the UCI. It had a stuttering start. The two organizers who run the bulk of professional events, Italy's RCS and France's AMAURY SPORT ORGANISATION, wished to retain the right to choose who rode their events and were worried that the UCI's agenda was to strip them of lucrative broadcasting rights.

The outcome was a four-year standoff with the governing body during which the Tour was

sometimes run outside UCI rules and antidoping regulations, with bitter exchanges of words that took the Tour organizers to the brink of breaking away to set up a “rebel” movement within the sport. Peace broke out in 2008, but the ProTour epitomized Verbruggen's legacy: radical and controversial.

sometimes run outside UCI rules and antidoping regulations, with bitter exchanges of words that took the Tour organizers to the brink of breaking away to set up a “rebel” movement within the sport. Peace broke out in 2008, but the ProTour epitomized Verbruggen's legacy: radical and controversial.

VUELTA A ESPAÃA

The third of cycling's great Tours along with the GIRO D'ITALIA and TOUR DE FRANCE, the Vuelta is also the youngest, founded in 1935, initially with the support of General Franco's military dictatorship (see POLITICS). Not surprisingly in a country hit by a dire civil war, the Spanish Tour took two decades to become established; the second edition in 1936, held shortly before the conflict began, was close to being canceled.

The third of cycling's great Tours along with the GIRO D'ITALIA and TOUR DE FRANCE, the Vuelta is also the youngest, founded in 1935, initially with the support of General Franco's military dictatorship (see POLITICS). Not surprisingly in a country hit by a dire civil war, the Spanish Tour took two decades to become established; the second edition in 1936, held shortly before the conflict began, was close to being canceled.

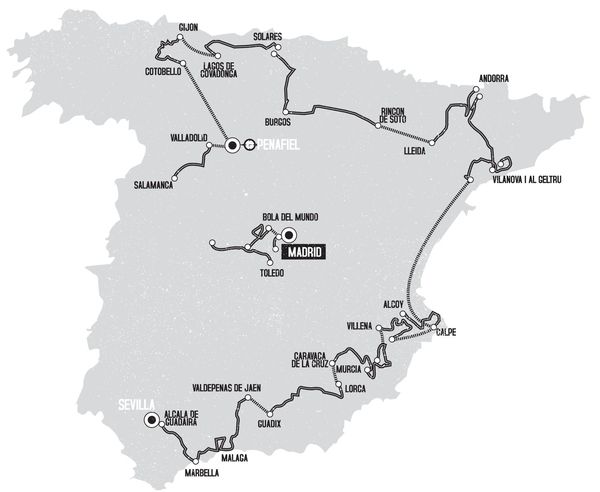

The Vuelta was not a regular fixture on the calendar until the mid-1950s and suffered for many years from a calendar date (mid-April to early May) that put off Italians preparing for the Giro, which began a few days after the Vuelta finish, and was too early for stars building to the Tour de France, but it has not been improved by a switch from April to September masterminded by HEIN VERBRUGGEN.

A showpiece finish on the Paseo de la Castellana avenue in the capital Madrid is traditional, but the heartland of the Basque Country is never visited, for political reasons (see POLITICS again). Sometimes the Vuelta seeks out Tour climbs in the Pyrenées but more often it heads for its own legendary ascents: the Puertos de Serranillos and de Navalmoral in the Sierra de Gredos west of Madrid, or the climb to Lagos de Covadonga in the lonely Cantabrian mountains on the Atlantic coast, home to some of the last wolves in Europe. The Sierra Nevada is another fixture.

Founded in 1935 by the

newspaper

Informaciones

, the Vuelta was shamelessly political, vaunting its “patriotism” at a time when that meant support for the right wing headed by General Franco; it was firmly linked with the regime. At first foreign stars had to be brought in for cash: FAUSTO COPPI was well past his best when he accepted 11,000 pesetas a day to ride the 1959 race while JACQUES ANQUETIL at least gave value for money in 1963 by winning.

newspaper

Informaciones

, the Vuelta was shamelessly political, vaunting its “patriotism” at a time when that meant support for the right wing headed by General Franco; it was firmly linked with the regime. At first foreign stars had to be brought in for cash: FAUSTO COPPI was well past his best when he accepted 11,000 pesetas a day to ride the 1959 race while JACQUES ANQUETIL at least gave value for money in 1963 by winning.

The Vuelta hosted occasional visits from the likes of EDDY MERCKX, who missed the 1973 Tour de France so he could win it while Hinault took a legendary victory in 1983, whipping the home stars but having to push so hard he damaged a tendon close to his knee and could not race for a year. The Vuelta truly began to feel like an integral part of the international cycling calendar only after Franco's death led to Spain's reintegration with the wider world, helped by the arrival in the 1980s of Spain's biggest star since FEDERICO BAHAMONTES, the charismatic, unpredictable Pedro Delgado.

Coat of Many Colors

=

Unlike the Tour and Giro, the Vuelta was not founded by a paper with distinctively colored pages; because of this, and because of the infrequency with which the race was run in the early years, its leader's jersey has changed color time and again.

| Light orange | 1935, 1936 |

| White | 1941 |

| Orange | 1942, 1977 |

| Red | 1945 |

| White with a red stripe | 1946â1948, 1950 |

| Yellow | 1955â2000 |

| Gold | 2001âpresent |

“Everyone has forgotten what it was like back then,” wrote LAURENT FIGNON, who rode the race in 1983. “Spain had only just emerged from the Franco era. It was like the third world; anyone who went over there at the start of the 1980s would know what I mean. For cyclists like us, the accommodation

and the way we were looked after were not easy to deal with. Sometimes it was barely acceptable. Professional cyclists of today cannot imagine what it was like in the 1980s in a hotel at the backside of beyond in Asturias or the Pyrenées. The food was rubbish and sometimes there was no hot water, morning or evening.”

and the way we were looked after were not easy to deal with. Sometimes it was barely acceptable. Professional cyclists of today cannot imagine what it was like in the 1980s in a hotel at the backside of beyond in Asturias or the Pyrenées. The food was rubbish and sometimes there was no hot water, morning or evening.”

Delgado's first Vuelta win in 1985 was hugely popular at home, even though to a non-Spaniard it was clearly a setup, with ROBERT MILLAR the victim. The arrival of “Perico” coincided with an economic boom in

Spain, and the beginning of live television coverage of the Vuelta. The number of Spanish teams blossomed and with MIGUEL INDURAIN dominant in the Tour de France from 1991â1995 Spanish cycling boomed briefly, even though Indurain never rode the Vuelta in his best years. Instead, the dominant forces in the 1990s were Swiss: Tony Rominger, who rode for a team sponsored by the Asturian dairy cooperative Clas, won from 1992â1994, while Alex Zülle, backed by the Spanish lottery ONCE, took the 1996 and 1997 races.

Spain, and the beginning of live television coverage of the Vuelta. The number of Spanish teams blossomed and with MIGUEL INDURAIN dominant in the Tour de France from 1991â1995 Spanish cycling boomed briefly, even though Indurain never rode the Vuelta in his best years. Instead, the dominant forces in the 1990s were Swiss: Tony Rominger, who rode for a team sponsored by the Asturian dairy cooperative Clas, won from 1992â1994, while Alex Zülle, backed by the Spanish lottery ONCE, took the 1996 and 1997 races.

As the 21st century dawned, the Vuelta appeared fragile yet again. There were rumors that the format might be tweaked and that it might revert to its old, popular spring date. It is now seen as a consolation race for those who have slipped up in the Tour de France, while some stars simply turn up to get a fortnight's preparation for the WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS and then go home to rest. The Tour organizers AMAURY SPORT ORGANISATION bought a 49 percent stake in the organizing company Unipublic, but of the big three, the Vuelta looked to have the least certain future.

W

WAR

An army cycling unit manual issued at the end of the 19th century recommended that when fighting cavalry its members should turn their bikes upside down and spin the wheels to spook the horses. It is not recorded whether or not this strategy was ever used in anger, but it reflects the reality of the day: the bicycle was more than a means for people to get about: its impact on personal mobility meant it was seen by the government as a key instrument in war.

An army cycling unit manual issued at the end of the 19th century recommended that when fighting cavalry its members should turn their bikes upside down and spin the wheels to spook the horses. It is not recorded whether or not this strategy was ever used in anger, but it reflects the reality of the day: the bicycle was more than a means for people to get about: its impact on personal mobility meant it was seen by the government as a key instrument in war.

Simply put, if you could get your foot soldiers into action quickly, that could change the outcome of a battle. Moreover, unlike conventional cavalry mounts, the bicycle did not need feeding and could be easily transported overseas. There were early proposals to put together fighting battalions mounted on HIGH-WHEELERS, but it was the advent of the SAFETY BICYCLE in the late 1880s that led to the formation of bicycle detachments.

The 26th Middlesex (Cyclist) Volunteer Rifle Corps, formed in 1888, was the first, with cyclists divided up according to their mounts: safeties, high-wheelers, TRICYCLISTS. The Middlesex numbered nearly 400. In 1906, cycling maneuvres involved 50 cyclist companies. There were experiments with defensive tactics against cavalry such as putting the cyclists inside a “fence” of cycles and trials with various tricycle-borne machine guns. Armed cyclists feature in “The Land Ironclads,” a short story written by H. G. Wells just before the First World War. In that conflict, the

British army included 14 cycle battalions, totalling 7,000 men, with folding bicycles made by the Birmingham Small Arms company (BSA) most commonly used.

British army included 14 cycle battalions, totalling 7,000 men, with folding bicycles made by the Birmingham Small Arms company (BSA) most commonly used.

The British were not the only ones using two-wheeled soldiers. Cycle maker Bianchi produced a folding bike in 1915 for the “

bersaglieri

,” the Italian light infantry, in 1915, which had fat tires and suspension for off-road use; it is claimed to be the precursor of the MOUNTAIN BIKE. The future double TOUR DE FRANCE winner Ottavio Bottecchia was part of a cycling squadron on the Austro-Italian front while the Tour de France founder HENRI DESGRANGE oversaw the training of 50,000 French cycling soldiers during the conflict.

bersaglieri

,” the Italian light infantry, in 1915, which had fat tires and suspension for off-road use; it is claimed to be the precursor of the MOUNTAIN BIKE. The future double TOUR DE FRANCE winner Ottavio Bottecchia was part of a cycling squadron on the Austro-Italian front while the Tour de France founder HENRI DESGRANGE oversaw the training of 50,000 French cycling soldiers during the conflict.

World War I cut short the careers of several greats: the 1907 and 1908 Tour winner Lucien Petit-Breton was killed near the front at Troyes in 1917, while other Tour winners to lose their lives were Octave Lapize, shot down in 1917 close to Verdun, and Francois Faber, killed in 1915 while carrying a comrade back to his lines through no-man's-land (see HEROIC ERA for more on these champions).

More fortunate was Paul Deman, first winner of the Tour of FLANDERS, who was a spy working for the Belgian secret service, smuggling documents into Holland on his bike. He was decorated for bravery by the English and French as well as his homeland; shortly before the war closed he was arrested by the Germans and sentenced to death, with the armistice happening just in time to save him.

There are other tales, such as that of the 1938 Tour winner GINO BARTALI: along the lines of Paul Deman, the “Pious One” pretended to go out training each day in occupied Italy but in fact he was a courier working for a resistance network riding between Florence and Assisi: he advised on train movements, but most important, hidden in his frame were forged documents

that were used to make fake passports enabling Jewish refugees to escape. The network is said to have saved some 800 lives.

that were used to make fake passports enabling Jewish refugees to escape. The network is said to have saved some 800 lives.

Bartali's great rival FAUSTO COPPI spent much of his war in a prison camp in North Africa; their teammate in the 1949 Tour de France Alfredo Martini, on the other hand, used his bike to ferry Molotov cocktails for the Italian partisans, a risky business on the rocky roads of the time. On a more sinister note, the VÃLODROME D'HIVER in Paris earned a grim reputation after it was used as a transit camp when the Nazis and French collaborators rounded up thousands of French Jews for transportation in 1942.

Numerous troops of cyclists also figured in combat in the Second World War; at the Normany landings, for example, paratroops were dropped with folding bikes, again made by BSA. The Germans used cyclist battalions in their invasion of Norway, and 20,000 cycles were vital in the Japanese attack on Singapore through supposedly impassable jungle. The cycle was the vehicle of choice for guerrilla groupsâbooby-trapped by Italians in Rome and by the Vietcongâwhile in the Vietnam war thousands of bicycles and porters were used to ferry supplies for the Vietcong. One senator remarked, only partly in jest, that it would be better to bomb their bikes than their bridges.

Switzerland maintained bike-borne troops into the 21st century while the Swedes kept them going into the 1980s. Both used heavyweight machines; the final Swiss bike, the MO-93, had seven-speed gears and carry-racks front and rear. The Swedish bike was sold under the Kronanbike label after Swedish army bikes kept finding their way onto the secondhand market.

The end of the First World War was marked, in spring 1919, by the running of the Circuit des Champs de Bataille, a seven-day stage race starting and finishing in Strasbourg along

the Western Front. The roads were barely recognizable, the riders ill-trained, and outside the major cities there was no food to be found. A truck followed the race carrying potatoes, meat, and butter. PARISâROUBAIX was also run that spring, through the devastated cities and ravaged countryside of Northern France.

the Western Front. The roads were barely recognizable, the riders ill-trained, and outside the major cities there was no food to be found. A truck followed the race carrying potatoes, meat, and butter. PARISâROUBAIX was also run that spring, through the devastated cities and ravaged countryside of Northern France.

“It's hell,” wrote HENRI DESGRANGE. “Shell-holes one after the other, with no gaps, outlines of trenches, barbed wire cut into 1,000 pieces; unexploded shells on the roadside, here and there, graves. Crosses bearing a jaunty tricolor are the only light relief.” That year's race was christened “Hell of the North” by another writer, and the name has stuck.

Bike racing across Europe never quite stopped during World War II, although the major Tours were not organized. The Tour de France organizer Jacques Goddet was always proud of the fact that he had refused to put on his race under occupation in spite of coming under pressure; the Giro, for its part, was replaced by a series of one-day races with an overall title, the Giro di Guerra. The Tour of Flanders was the only major event to be run in an occupied country, and did so with German police help; this led to controversy after the conflict. In France, races were run virtually up to Liberation in both the occupied and non-occupied zones, as Jean Bobet relates in his detailed

Le Vélo a l'Heure Allemande

(

Cycling in German Time

, La Table Ronde, 2007). In Great Britain, the near-absence of traffic on wartime roads enabled Percy Stallard to bring in road racing, European style.

Le Vélo a l'Heure Allemande

(

Cycling in German Time

, La Table Ronde, 2007). In Great Britain, the near-absence of traffic on wartime roads enabled Percy Stallard to bring in road racing, European style.

WATSON, Graham

(b. England, 1956)

(b. England, 1956)

The first Anglophone photographer to break into the tightly knit group of snappers who shoot European cycle racing and who consequently has done much to popularize the sport in English-speaking nations over the last 30 years. Like TV commentator PHIL LIGGETT, Watson started as a bike racer; he spent time working in a London photo studio and began his photography career shooting for

Cycling

magazine. He moved to

Winning

in the 1980s where he made his name thanks to his work with breakthrough stars such as SEAN KELLY and GREG LEMOND, and thanks to one sequence of pictures in particular showing Jesper Skibby being run down by the organizers' car in the Tour of FLANDERS.

Cycling

magazine. He moved to

Winning

in the 1980s where he made his name thanks to his work with breakthrough stars such as SEAN KELLY and GREG LEMOND, and thanks to one sequence of pictures in particular showing Jesper Skibby being run down by the organizers' car in the Tour of FLANDERS.

He has been a fixture at leading US magazine

VeloNews

for many years and has been close to LANCE ARMSTRONG since the Texan turned pro in 1992. As well as selling pictures and annual calendars and working for many of the top teams, Watson has produced over 20 books, including inside accounts of his life in bike racing. These offer a different perspective to that of most writers, because motorbike-borne photographers have unique access to the decisive moments of the greatest races.

VeloNews

for many years and has been close to LANCE ARMSTRONG since the Texan turned pro in 1992. As well as selling pictures and annual calendars and working for many of the top teams, Watson has produced over 20 books, including inside accounts of his life in bike racing. These offer a different perspective to that of most writers, because motorbike-borne photographers have unique access to the decisive moments of the greatest races.

WEIGHT

An obsession for professional cyclists. The story goes that when the Italian trainer Luigi Cecchini began working with the Dane Bjarne Riis, he handed him two kilogram bags of sugar and said: imagine riding with that lot under your saddle. Riis lost a few kilos and won the 1996 Tour, albeit, he later confessed, with the help of EPO as well. There are also tales of riders training with weights under their saddle, although none now go as far as Jean Robic, the 1947 Tour

winner, a featherweight who would collect a

bidon

containing 10 kg of lead at the top of a mountain to help him keep up on the descent.

An obsession for professional cyclists. The story goes that when the Italian trainer Luigi Cecchini began working with the Dane Bjarne Riis, he handed him two kilogram bags of sugar and said: imagine riding with that lot under your saddle. Riis lost a few kilos and won the 1996 Tour, albeit, he later confessed, with the help of EPO as well. There are also tales of riders training with weights under their saddle, although none now go as far as Jean Robic, the 1947 Tour

winner, a featherweight who would collect a

bidon

containing 10 kg of lead at the top of a mountain to help him keep up on the descent.

The importance of weight loss when climbing is clearly illustrated, although the precise effects vary from rider to rider, because of factors such as the steepness of the hill, the rider's power output, and the percentage of a rider's weight that is lost. One estimate (MICHELE FERRARI's) is that a kilo adds 1.25 percent to a rider's time up a hill. That means, in essence, that for each kilo a rider is heavier, he is having to work 1.25 percent harder.

The ratio between the power a cyclist can produce without “blowing up”âsustainable powerâand his weight is the key figure: Ferrari estimated that the figure a Tour winner needs to produce is 6.7 watts per kilo (quoted in Dan Coyle,

Tour de Force

). In 2009, weight loss was one of the keys to BRADLEY WIGGINS's transformation into a TOUR DE FRANCE contender: the Briton went from 77 kg at his track racing weight to 73 kg. Critically, he lost weight while minimizing his loss of power. His trainer estimated that even at his Tour weight, he would still be able to ride a 4,000 m pursuit at 4 minutes 15 seconds pace, only slightly slower than he was doing in training in the run-up to the Beijing OLYMPIC GAMES.

Tour de Force

). In 2009, weight loss was one of the keys to BRADLEY WIGGINS's transformation into a TOUR DE FRANCE contender: the Briton went from 77 kg at his track racing weight to 73 kg. Critically, he lost weight while minimizing his loss of power. His trainer estimated that even at his Tour weight, he would still be able to ride a 4,000 m pursuit at 4 minutes 15 seconds pace, only slightly slower than he was doing in training in the run-up to the Beijing OLYMPIC GAMES.

WHEELS

Relative to its weight, the bicycle wheel is one of the strongest man-made constructions, having to take loads in various planes: up and down (radialâthe rider's weight, bumps in the road, braking), side to side (lateralâparticularly where the rider is standing on the pedals to climb a hill), and twisting (torsionalâthe circular motion from the chain and sprockets that drives the bike forward). An experiment with a conventional wheel built by Condor Cycles estimated its

working load-to-weight ratio at about 400-1.

Relative to its weight, the bicycle wheel is one of the strongest man-made constructions, having to take loads in various planes: up and down (radialâthe rider's weight, bumps in the road, braking), side to side (lateralâparticularly where the rider is standing on the pedals to climb a hill), and twisting (torsionalâthe circular motion from the chain and sprockets that drives the bike forward). An experiment with a conventional wheel built by Condor Cycles estimated its

working load-to-weight ratio at about 400-1.

Early BONESHAKERS featured wheels of “West Indian hardwood, amaranth, makrussa, hickory or lemon tree”; wood continued to be used for rims, particularly for track racing, up to the Second World War. They were made either by turning a single strip into a hoop and biscuit-jointing the ends, or by lamination.

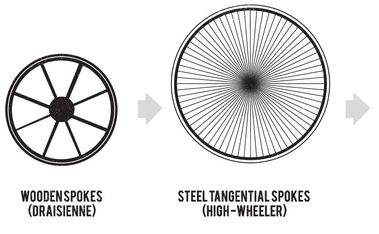

The development of the HIGH-WHEELER led to a focus on wheel design and a gradual evolution from the cart-type wood spoked wheels used by early cycles such as the DRAISIENNE. The key development came in 1870 when JAMES STARLEY patented the Ariel high-wheel cycle. This had wheels on which the spokes were tensioned so that the riders' weight was suspended; four years later, Starley introduced tangential spoking, in which the spokes ran at opposing angles, crossing over each other.

Steel rims were initially ubiquitous, with wood used for racing, but aluminium gradually took over, with the main market difference whether the rim was single walledâone layer of metalâor double walled, with two, for greater strength. Over 130 years later, specialist rim-makers such as France's Mavic, makers of the legendary SSC black-anodized tubular rim (Special Service des Courses) still supply this kind of rim.

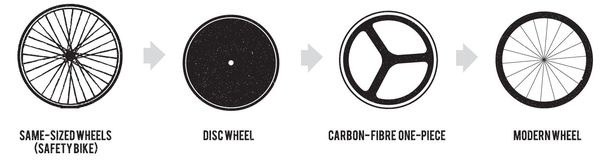

But at the racing end of the market, there have been other developments in recent years. The first disc wheel design appeared in 1892. The idea was that it would be more AERODYNAMIC than spoked wheels, but there were already questions about how it would perform in side winds. It was not until FRANCESCO MOSER smashed

the HOUR RECORD in 1982 that disc wheels came back into the picture. The breakthrough was in the idea that on the flat at least aerodynamics mattered more than weight. Moser's use of the wheels was challenged but his lawyers won the case by arguing that the wheels actually had one single spoke.

the HOUR RECORD in 1982 that disc wheels came back into the picture. The breakthrough was in the idea that on the flat at least aerodynamics mattered more than weight. Moser's use of the wheels was challenged but his lawyers won the case by arguing that the wheels actually had one single spoke.

Carbon-fiber discs are now ubiquitous wherever pure speed matters: time trials on road and track and track endurance races. Rear discs are always used, with the choice of a front disc depending on wind conditions, as wind from the side can affect the bike's stability. Variants on the disc include one-piece carbon wheels with three or four vast flattened spokes.

From 1994 when CAMPAGNOLO brought out the Shamal, the top end of the racing and then the CYCLOSPORTIVE market was gradually taken over by deep-rimmed wheels, which had a V section rather than the traditional shallow U. These are put together in the manfacturer's factory, rather than lovingly crafted from individual spokes, rims, and hubs in a wheelbuilder's shop. “Factory-built” wheels, carbon-fiber for racing, aluminium for training, are now the gear of choice, and in a time trial, one will be used at the front end rather than a disc. Virtually every cycle component maker has gotten in on the act.

Other books

Hopeless For You by Hill, Hayden

The Expatriates by Janice Y. K. Lee

The Ivy League by Parker, Ruby

A Vampire's Christmas Carol by Eden, Cynthia

Windfalls: A Novel by Hegland, Jean

LZR-1143: Redemption by Bryan James

Only the Good Spy Young (Gallagher Girls) by Carter, Ally

Anything Can Happen by Roger Rosenblatt

Last Train to Paradise by Les Standiford