Daily Life During the French Revolution (11 page)

Read Daily Life During the French Revolution Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

Many travelers, in spite of proper documents from the

customs at Calais and bags closed with lead seals, were searched again upon

entering Paris. Not only did unexpected delays at custom houses inconvenience

people and cost them money, but also they caused havoc with internal trade

conducted by legitimate businessmen right up to the time of the revolution.

Even going down the Rhône from Lyon by boat, passengers were forced to wait at

Vienne, only about 20 miles south, to be once again inspected by customs

officers, recorded Lord George Herbert.

An indignant Reverend William Cole refused to pay any more

bribes to custom officials when he reached the gates of Paris in 1765, and his

luggage was thoroughly searched for contraband goods. Found was a pair of new

boots, and when the officials claimed that no new goods were allowed without

payment, the reverend told them to take the boots at their peril, but he was

not paying. After some time and probably an unpleasant altercation, they let

him pass. Most travelers paid to avoid the inconvenience.

Philip Thicknesse, an English army officer who made many

trips to France before the revolution, reported that there were ways to quickly

get through the internal customs barriers—“a twenty-four sols piece and on

assuring the officer that you are a gentleman and not a merchant, will carry

you through without delay.” He returned in 1801, well after the revolution, and

wrote: “You are not now plagued, as formerly, by customhouse officers on the

frontiers of

every

department, My Baggage, being once searched at

Calais, experienced no other visit.”

Having reached Paris, many travelers found the buildings

too tall and the streets too narrow and dirty; in addition, many of the streets

lacked sidewalks, making them a danger to pedestrians. This was often commented

on by both foreigners and French. There were other problems also: Dr. John

Moore, who was there in 1792, complained that “Paris is poorly lighted” and

that people “must therefore grope their way as they best can, and skulk behind

pillars, or run into shops to avoid being crushed by the coaches.”

Others reported that carriages clattered along at top

speed, and it was the responsibility of those on foot to jump clear. There were

many injuries and deaths in the city from passing coaches that often did not

even bother to stop.

FRENCH TRAVELERS

When Fréron and Barras, two representatives of the

revolutionary government, were sent on a mission to Marseille, Fréron sent back

a letter to the Convention on December 12, 1793, to counter accusations that

they were living in luxury. He claimed that they were not dining in the style

of a tax collector and indeed ate only one meal a day, at four in the

afternoon, and sometimes they gave a bowl of soup to hungry sans-culottes if

they asked for it. Fréron also mentions how hard he worked, not going out for

several days but instead sitting in his dressing gown writing his reports. If

he did go out at all, it was only for a few hours to get some fresh air. He had

no time to see any women because he was much too busy working for the nation

(which he loved a hundred times more). The two men lived at an inn and dined

alone to save money.

He wrote about Marseille and the work they were going to do

there. Since there were no police in the city, he and Barras established a

police force. They discovered four gaming houses where the people addressed

each other as Monsieur and Madame and the louis cost 60 livres in paper money:

“We are going to raid the gamblers tomorrow morning. Marseilles is going to be

paved and cleaned up, for it is of a horrible filthiness. Moreover, this will

give employment for many idle hands.” To bring the city into line, one of the

deputies stated, with regard to prostitutes, “all the public women who infect

our volunteers and entice them away from the army shall, within two days be

placed under arrest. The order has been signed and a place readied to receive

them. Diseased girls will receive treatment and healthy ones will work at

sewing uniforms or shirts for the brave defenders of the

Patrie.

”

As a result of a decree passed by the Convention on October

8, 1793, for the requisitioning of horses for the army, the country had been

divided into 20 sections, each assigned to a representative. The deputy

Goupilleau de Montaigu, from the west, made several trips to the south from

1793 to 1795. He did not depart on horseback or in a two-wheeled buggy but

instead hired a four-wheeled carriage and three horses to pull it. On the roof

he placed an enormous hamper for his personal effects. Horses and postilion

were changed at each posting house, which were not far apart. Citizen

Goupilleau spent enough just getting to his first destination: 25 sous for each

horse, and another 10 for the postilion or guide; about 25 sous to cross rivers

and streams by ferryboat, not to mention the charges for lodgings at inns and

for meals. Bolstered with many cushions, he was able to travel comfortably,

observe the countryside, and take notes.

Lyon was not to his liking: the narrow streets were badly

paved and muddy, and the houses, in his opinion, were not as nice as those in

Nantes. After passing Vienne, on October 15, he felt he had reached the south,

for the weather turned warm. On his way to Valence, he remarked on the

shallowness but the fast flow of the Isère River as he crossed it by ferry and

noted that the life of the people seemed to change with the scenery, becoming

more relaxed. The mulberry and almond trees and large, black swine seen along

the side of the road suggested a more carefree existence than existed in the

north. On October 17, at Mondragon, he saw more mulberries but also fig and

olive trees. He found the food good and the wine excellent at Avignon, but the

innkeepers, he said, were rogues who “lavish attention on you when you arrive

and skin you alive when you depart.” On October 19, at seven in the morning, he

arrived at Arles complaining that the mosquitoes kept him awake all night and

that he had been forced to close the window of the coach. Next stop was Aix,

whence he went on to Marseille, which, contrary to Fréron, he found to be a

beautiful city comparable to Nantes, although the theater was not as good and

the port was only a large pool surrounded by rundown buildings. He complained

about the prices of the inns whose keepers, as at Avignon, he claims were of

“Italian” mentality.

Madame Simon, the mistress of the Hôtel de Beauveau,

charged him extremely high prices, and he swore never to return there. He did

find in his expensive room, however, a wonderful invention that allowed him to

sleep well—a mosquito net draped around the bed.

He visited many other cities where he was grandly received

by the town dignitaries. In the Jacobin town of Antibes, where patriotic fervor

was at a high pitch, many of the streets were named after recent revolutionary

events, such as July 14. Then, on to Nice where again he found the streets too

narrow, but he admired the Place de la République. Generally he found the

inhabitants of the south very honest and decent but fatiguing. A man from the

more formal west, he complained that he could not walk a step without being

surrounded by chatter. He was forced to eat and drink too much by amicable and

generous southerners. On his return to Paris, he again stopped at Arles and

remained there for a month, until December 6, attending to his mission of

requisitioning horses. While there, he was dragged off to a bullfight but

thoroughly disliked the spectacle of animals engaged in combat before they were

slaughtered, simply for the amusement of people, comparing it to Roman

barbarism. His other missions were also replete with festivals, gastronomic delights,

and fine wine, the price of which was well out of reach for most Frenchmen.

Apparently, for some, it was splendid to be a deputy

en mission.

4 - LIFE AT VERSAILLES

THE PALACE

The

palace at Versailles was the wonder of Europe, a monument to Bourbon power and

wealth. The main buildings, comprising decorated halls, galleries, apartments,

state rooms, terraces, and courtyards, were surrounded by vast formal gardens

that included lawns, bushes, trees, and sculpture intersected by broad gravel pathways.

There were numerous secluded groves and a mile-long Grand Canal. The many

fountains played all around, and manmade lakes were home to swans. North of the

gardens stood the Grand and Petit Trianons, or royal villas. The Petit Trianon

was a favorite retreat of Marie-Antoinette.

There was another side to the palace besides its intricate

beauty and grandeur, however. The many chimneys did not draw well, and

throughout the winter rooms were full of smoke and the upholstery, wall

hangings and carpets smelled of soot, the odor permeating clothes and wigs.

Servants and aristocratic visitors often relieved themselves on back stairs,

along the darkened corridors, or in any out-of-the-way place. The writer Horace

Walpole agreed with other English visitors to Versailles that the approach was

magnificent but the squalor inside was unspeakable. The stench of urine and

fecal remains wafted through corridors and gardens where waste water was often

emptied from the windows. Sometimes garbage was dumped on the royal grounds by

local peasants. Cats and dogs roamed freely, many wild, leaving their calling

cards on paths and roads and in the shrubs. Madame de Guéménée, governess of

Louis XVI’s two sisters, went about the palace with an escort of dogs that she

kept in her rooms. She feigned communication with the spiritual world through

them.

Just about anyone could enter the palace and wander about

its broad hallways and spacious salons. Visitors from Paris strolled through

the corridors admiring the

objets d

’

art

and furnishings, watched

by servants who, no doubt, looked on with dismay at the parade of muddy boots

and dirty paws. Dignitaries and ambassadors from foreign courts brought their

entourages to Versailles and filled rooms of the palace and town with servants,

slaves, camp followers, and exotic pets. About 10,000 people lived or worked in

the palace.

FINANCES

Debt was part of everyday life for the royal court and the

nobles who lived there, but it was not of any great concern, and everyone

reckoned that it would be paid off eventually. Huge expenses were incurred when

each of the royal children was born, with the usual fanfare in Paris of booming

cannons, bonfires, pyrotechnics, music, and plenty of free wine. Many Parisians

loved the celebrations but were not pleased when another palace, St. Cloud, was

purchased for the queen. The money was said to have come from selling other

crown lands, but Parisians were skeptical, assuming that more millions of

livres had been added to the debt. They began calling the queen Madame Deficit,

among other unsavory names.

Further, they were angry when Marie-Antoinette singled out

the Polignacs for favors. In 1777, Yolande de Plastron, comtesse de Polignac,

became a close and intimate friend of the queen, who lavished expensive gifts on

her. Before long, her husband, who was not well off, began to attain high,

lucrative offices. In one year (1780), he was made the first equerry to the

queen, grand falconer of France, and governor of Lille. In a position to spread

his largesse around, he made his portrait painter, Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, the

most important artist at court and her brother one of the many secretaries of

the king (which gave him noble status). Vigée-Lebrun’s art-dealer husband also

received a constant stream of wealthy customers.

The list of Polignac appointments to the royal household

grew and grew, and eventually the entire family and relatives had lucrative

posts. An ample pension was given to a monk who happened to be related, and

even remote members of the family received gifts and annuities, all of which

amounted to tens of thousands of livres. This kind of extravagant spending, and

the huge state pensions given to Marie-Antoinette’s favorites, aroused a good

deal of indignation among the people. In 1776, the entire annual household

budget of the court amounted to about 30 million livres, of which about 3

million went to the Polignac clan. The average Parisian worker of the time

received about two livres a day.

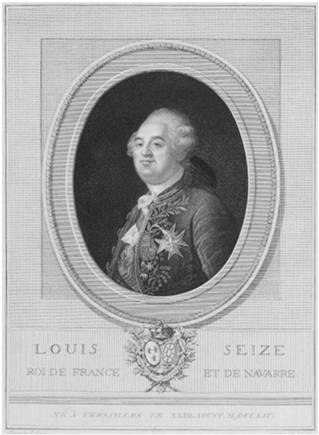

Louis XVI, King of France and Navarre.

DAILY LIFE