Daily Life During the French Revolution (34 page)

Read Daily Life During the French Revolution Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

An execution in the Place de la Grève was an occasion for

fellow workers, as well as the women, to go in their groups to watch the

gruesome public act. Even the back streets served as places of outdoor

entertainment; men played skittles while the women watched. Children ran wild

in the streets chasing each other or engaged in mock fights using sticks as

muskets or swords or amused themselves with spinning tops or playing quoits,

skittles, or ball games.

On feast days and Sundays, everyone disgorged from their

dingy, crowded apartments and took to the streets, hailing friends and acquaintances

as they passed. Most of the people in rundown quarters of the city were

laborers—just above the beggars on the social ladder.

The people might be ground down by poverty and have their

petty quarrels and lives exposed to the intrusive scrutiny of neighbors, but

such closeness could be beneficial. A master craftsman and his wife who lived

on the ground floor in comparative luxury, a journeyman on the next floor with

his small family, a laborer on the third level with his working wife, and a

penniless widow in the attic who made a few sous mending shirts— all were

polite to one another and exchanged greetings. If the widow had not been seen

on her daily walk to the grocer’s, someone would check to make sure she was all

right. If a violent quarrel seemed to put a woman in danger from a brutal husband,

it would not be uncommon for the neighbors to knock on the door to inquire

about her and even break it down if the situation seemed desperate for the

woman. Bailiffs coming to seize goods or apprehend someone who could not pay

his debts often encountered resistance from the neighbors who drove them off,

forcing them to try another day. What appeared to be an unjust arrest in some

quarters might well degenerate into a local riot in support of the victim.

People also kept an eye on one another’s property: a stranger in the building

was cause for alarm and was watched closely.

The inhabitants of a poor quarter worked 14 or 15 hour

days; a single shop girl might rise at four in the morning, spend all day in

the shop, and come home about seven to prepare a little food and eat alone; but

everyone put a high value on integrity and self-respect and generally addressed

others using the esteemed terms

Monsieu

r and

Madame.

WORK AND LEISURE

To create a trade corporation, the king had to ratify the

corporation’s statutes by

lettres patentes

. With the king’s sanction, it

became a

métier juré,

or sworn trade, and anyone who became a master of

the trade was required to sign an oath of loyalty to the corporation. To learn

the trade, a young man or woman began as an apprentice; the ambition of most

apprentices was to become a master of the craft. The apprenticeship usually

began when the boys or girls were teenagers and lasted from three to six years.

Apprentices were required to undertake a test of their skills by producing an

original work judged acceptable by a jury of masters. For example, an

apprentice seamstress had to create a pleasing dress or gown to fulfill the

requirement.

In addition, candidates also needed sufficient money to buy

the mastership from the corporate community. During the apprenticeship, filial

subordination to the master was part of the process sanctioned by a legal

contract.

Journeymen, skilled workmen who had already served an

apprenticeship, were hired for wages without long-term contracts to bind them

to the master. Many were married and had families, and they retained their

position in society as journeymen, usually for life, for, while they were hired

to help the master, they seldom reached mastership themselves. Excluded from

the confraternities of the masters, they formed parallel associations that had

no standing in law but had elaborate rituals that were often kept secret. For

itinerant young journeymen, the organization kept rooming houses in various

cities and offered aid in times of sickness and when a member died.

It was expensive to set up in business. In Paris, a little

before the revolution, the cost of a mastership ranged from 175 livres for a

seamstress to as much as 3,240 livres for a draper. Most corporations charged

between 500 and 1,500 livres, but often this was more than a journeyman could

earn in a year. Becoming a master offered many advantages, however. The master

was assured of a place in the market and protection for his goods, which no one

else was allowed to produce. His living standard was comparatively good, and in

hard times he could draw on the charity of his trade’s confraternity. Overall,

a mastership meant prestige and security for one’s family, and one’s children

had access to mastership at half the usual price. The master’s position and

privileges could be inherited by his widow until such time as she remarried or

turned them over to a son. Because of his status, the master was able to get credit,

and enhanced income often allowed him to buy property, which raised him even

higher in his social milieu.

Then, on March 2, 1791, the revolutionary government

dissolved the guild corporations. The corporate body and its regulations were

no longer relevant. Former masters, who were now called entrepreneurs, could

arrange contracts individually without corporate authority. There were also now

no legal barriers preventing a journeyman from becoming a master and

establishing a business for himself. If the business did badly, he faced the

prospect of falling into the ranks of the wage earner, since there was no

longer a corporate body to ensure him a place in the market or to lend

financial assistance. Masters had to take their chances as employers in an unregulated

open market.

For the working man or woman, the monotony of life on the

job was regularly alleviated by local events. Besides religious holidays,

secular festivities and celebrations took place in the quarters throughout the

year, and one of the most elaborate and colorful was Carnival, when streets

were replete with people wearing costumes and masks. Bonfires were not unusual,

although the police discouraged them as a fire risk. Children marched around

beating drums, and there was dancing, drinking, and socializing, with few

settling into bed before the early hours of the morning. Itinerant actors

presented bawdy plays and burlesque on makeshift stages, while magicians,

acrobats, ballad singers, and puppet shows vied for the crowd’s attention and

its money.

Young country girls often found life on the family farm

tedious and longed to go to the city to find jobs as clerks or apprentice

seamstresses. This could, in fact, relieve the large family of the extra mouth

to feed, and the girl also might be able to send a little money home once in a

while. Paris was generally the preferred destination for such young people. The

working life of a single girl in the city was not an easy one. Girls who became

apprentices worked hard for meager pay, slept in dormitories, and had little to

eat. On Sundays, about half a dozen pounds of meat were stewed in a large pot;

this had to feed everybody in the workshop for a week. The woman in charge sent

the girls out on occasion to the local markets to purchase bread at a price

much cheaper than in the bakeries, and it, too, had to last the week.

Walking through the streets of Paris during the time of the

Terror could be a traumatic experience, especially for young girls or boys

straight from the country. Cattle carts passing by on their way to the river

were sometimes piled high with the bodies of men and women recently butchered.

As the wagons bounced over the cobblestones, arms and legs dangled from the

sides like puppets on a string, trickles of fresh blood falling on the roadway.

At the river, the bodies and their separated heads were thrown into the water

to drift downstream toward the ocean. Only a short time before, the victims had

made the journey in the same tumbrels down the rue St. Honoré to the

guillotine. Working in their shops as the carts passed, Parisians often didn’t

even look up, according to eyewitness reports, or turned their backs on the

gruesome spectacle.

When people went into the streets of Paris, they made sure

they were wearing the tricolor cockade on their hats, which identified them as

patriots, whether they were or not. It was not wise to reveal any subversive

characteristics or thoughts to anyone at any time. To be denounced as a traitor

could mean a place in the tumbrels.

THE PARIS QUARTERS

Not unlike many other large European cities, Paris was

composed of many districts or quarters, each with its distinct people and

atmosphere. The wealthy middle class and the nobility occupied the faubourg St.

Germain, as well as the Marais, the Temple, and the Arsenal districts.

The working-class areas had their special occupations: the

masons lived in St. Paul; the furniture and construction industries were

situated in Croix-Rouge; and milliners, haberdashers, and producers of other

fashionable goods inhabited the rue St. Denis and the rue St. Martin.

To the north of the city, the residents of the suburbs of

Montmartre, St. Lazare, and St. Laurent were engaged mainly in the sale of

cloth. In Chaillot, to the west, were ironworks and cotton mills, while the suburb

of Roule, known as Pologne (Poland, as it was the home of many Polish

immigrants) was one of the poorest neighborhoods in Paris. East of the city on

both banks of the Seine lay the suburbs of St. Antoine and St. Marcel, where

furniture workshops were situated, along with the Gobelins tapestry works, dye

works, and Réveillon’s wallpaper factory.

Doing the same jobs, frequenting the same taverns, and

marrying local girls, the workers seldom ventured beyond their districts.

Events happening in one section of the city were not even known about in

others, as people were generally indifferent to what was going on elsewhere.

Difficulties of transportation and traffic compartmentalized the city, and

reactions to political events were different in the various sections.

Housewives shopping at the local market might be totally

unaware that people were being massacred nearby. News, spread by word of mouth,

could take several days to reach all parts of the city, and everything was

extremely susceptible to exaggeration and rumor.

For those curious people willing to travel further afield

to hear the most recent news, there were meeting places where discussions took

place. The Jardin des Tuileries, earlier a fashionable parade ground, became

the open-air anteroom of the Assembly, and the Place de la Grève was used for

executions, mass gatherings, and parades of the National Guard. The most

popular meeting place was the gardens of the Palais Royal. Here was the center

of cafe life, restaurants, entertainment, and the favorite haunt of agitators,

soapbox orators, rabble-rousers, scandalmongers, prostitutes, and demagogues.

The galleries along the arcaded sidewalks had been rented out to tradesmen by

the duke of Orléans some years before and had become the noisiest and, for the

future of the royal crown, the most dangerous place in the city.

The marquis de Ferrières, a provincial nobleman, having

visited the Palais Royal, stated:

You

simply cannot imagine all the different kinds of people who gather there. It is

a truly astonishing spectacle. I saw the circus; I visited five or six cafés,

and no Molière comedy could have done justice to the variety of scenes I

witnessed. Here a man is drafting a reform of the Constitution; another is

reading his pamphlet aloud; at another table, someone is taking the ministers

to task; everybody is talking; each person has his own little audience that

listens very attentively to him. I spent almost ten hours there. The paths are

swarming with girls and young men. The book shops are packed with people

browsing through books and pamphlets and not buying anything. In the cafés, one

is half-suffocated by the press of people.

Most visitors never ventured into the old quarters but

stayed in the hotels in the more affluent areas. However, that the capital was

lively, noisy, and vivacious is evident from reports of foreigners who visited

the city. A German bookseller and writer named Campe, who visited Paris in

1789, noted that not only were the people polite and animated in conversation

but also that everybody was

talking,

singing, shouting or whistling, instead of proceeding in silence, as is the

custom in our parts. And the multitude of street vendors and small merchants

trying to make their voices heard above the tumult of the streets only serves to

make the general uproar all the greater and more deafening.

Campe, a refined gentleman from a sedate and somewhat dull

country compared to France, went one evening to watch the sunset from the Place

Louis XV and suddenly found himself assailed by three old harpies who tried to

kiss him and at the same time snatch his purse. Fortunately, he got away

unscathed. Some witnesses found life in Paris harrowing, with the crowds,

noise, smells, dirt, and abundance of people from the provinces looking for

work, some of whom were desperate for a handout of a few sous. A lot of these

wound up working in the quarries of the Butte Montmartre.

Some 4,000 of the nobility lived in Paris. The revolution

brought about the first exodus of aristocrats from the city on July 15, 1789;

the second and larger one took place after October. Those who remained found

life rather boring, since there were no more grand balls and even concerts had

been eliminated. Night patrols kept the streets peaceful and aristocrats

indoors. As people left the richer districts for exile, trade slowed down and

money became scarcer.

A NOBLEMAN IN THE ESTATES-GENERAL

The marquis de Ferrières, a public figure in Poitou,

divided his time between his chateau in Marsay and his grand house in Poitiers.

A student of the philosophers of the Enlightenment, he published three essays

on the subject. His satire on monastic vows earned him a reputation as an

intellectual and led the nobility of Poitiers to elect him as their

representative to the Estates-General. He kept up regular correspondence with

his wife after his arrival at Versailles. Like the majority of deputies, he

deplored the move to Paris and complained that the streets of the city were

rivers of mud in the constant rain and that he did not go out at night for fear

of being run over by carriages. Instead, he spent the time alone and sad,

seated by the fire. He invited his wife to join him in Paris, but they needed

servants, so he asked if the cook at Poitiers would be able to dress her

mistress? Would she sweep the floors and make the beds? If she was not

agreeable, he would rather have the little chambermaid, who could help with the

washing and manage some cooking. Madame de Ferrières arrived in Paris and

passed two winters there, but in the summers of 1790 and 1791 she returned home

and her husband continued to write to her about domestic affairs. In August

1790, the marquis stated that he was highly satisfied with Toinon, his servant,

who gave him every attention, and wrote about his diet, which consisted of

beans, haricots, cucumbers, and very little meat. He dined with another noble

deputy from Béziers, who shared expenses with him helping to keep costs down.

He declared that in the preceding month, the cost of provisions (butter, coal,

vegetables, fish, and desserts) had amounted to 118 livres, and bread had cost

another 30 livres. This sum did not include meat and wood, or lodging at three

livres a day. Toinon was later replaced by a girl, Marguérite, who was

excellent at making vegetable soup. The staff also included a manservant called

Baptiste, a short, jolly man who liked coffee and sneaked a cup whenever he

could, ate too much meat, and spent his free time entertained by the

marionettes in the Place Louis XV. The marquis said he had only one serious

shortcoming: when he went down to the wine cellar, he always came back reeking.

CAFE SOCIETY

In the summer of 1789, cafe society was in full swing, and

there was more to discuss and argue about than ever before. The tables on the

sidewalks were packed with people sipping everything from English and German

beer to liqueurs from the French West Indies, fruit drinks, wine, Seidlitz

water, and a host of other cathartic and herbal tonics, as well as coffee and

chocolate-flavored drinks. Signboards advertising the cafes were on every

corner, gallery, and arcade. In front of the famous cafe Caveau, great throngs

gathered until two in the morning. Each establishment was well known for some

specialty: the Grottes Flamande for its excellent beer, the Italien for its

beautiful porcelain round stove, and the Café Mécanique for the mocha pumped up

into patrons’ cups through a hollow leg in each table. Of the many and varied

places, the Café de Foy was the most popular of all, with its gilded salons and

a pavilion in the garden. A fine brandy from the provinces was its trademark.

In the rue des Bons-Enfants stood the Café de Valois,

frequented by many of the Feuillants reading the

Journal de Paris

, while

the Jacobins were regular patrons of the Café Corazza, where François Chabot

and Collot d’Herbois often held the floor. In the rue de Tournon was the Café

des Arts, the focal point of the extremists from the Odéon district, while more

moderate types congregated at the Cafe de la Victoire, in the rue de Sèvres.

The differences in clientele could be striking. At the Régence, on the right

bank of the Seine, Lafayette was greatly loved, but at the Cafe de la Monnaie,

on the rue de Roule, the sans-culottes burned him in effigy. The Café de la

Porte St. Martin attracted quiet, respectable people out for an evening stroll.

As varieties of opinion were expressed, a man was judged by the cafe of his

choice. Rarely seen in cafes before, women began to follow the example of the

men and appeared in the evenings at the popular gathering places. They were

welcomed, as it was good for trade—the cafe trade, which was to endure all

upheavals and which persists until the present day.

Paris was not alone in the development of cafe society. All

the major cities and towns of the country began to enjoy the companionship and

the stimulation of discussion in their favorite bistros. Owners were exposed to

certain occupational risks, as, on occasion, heated discussions led to dishes

and cutlery being hurled across the tables. Major topics under discussion in

the news sheets and by sidewalk orators were the revolution, politics, members

of the government, trade, colonies, finances, taxation, and the huge deficit.

FREEMASONRY

Imported from England in the early 1700s, Freemasonry had

by the end of the century reached 700 lodges, with 30,000 members, distributed

throughout all the major cities. Many of the revolutionaries were prominent

Freemasons. Louis-Philippe Orléans, cousin of the king, was Grand Master, and

others included Georges-Jacques Danton, Marie-Jean Condorcet, and Jacques-Louis

David. Individual Masons were very active within the new society, some working

through the press and literary societies to make people aware of imminent

political change. They were generally well educated, often drawn from the

wealthier families and an important element, not unlike the salons, in

spreading enlightenment ideas. Men of all shades of opinion were recruited by

the lodges. The “Committee of Thirty,” which contained many prominent men, met

mainly at the house of Adrien du Port and put out pamphlets and models for

petitions or grievances and gave its support to political candidates. How much

Freemasonry influenced the course of the revolution remains to be clarified,

however. The majority of members were bourgeois who approved of the Masonic

abstract symbol of equality; yet the organization’s hierarchical structure

conflicted with the egalitarian principles of the revolution.

In the army, too, Masons were to be found, especially among

the officers. Some claim that the election committees of the Estates-General

consisted mainly of Masons. Freemasons were in general considered suspect by

the Catholic Church, but although they preached a “natural” religion, they did

not necessarily look for the separation of the church from the state. In

general, Freemasonry attracted men who were interested in philanthropy,

fraternity, and friendship (being open to greater social mixing than other

old-regime groups), and in new political ideas.

The number of lodges reflected the strength of the

bourgeoisie and other non-noble groups of the Third Estate. Not all Masons

became revolutionaries, but the lodges were present in many revolutionary

municipalities, and their influence was palpable. Men who aspired to be

politicians thus might have found it advantageous to join and benefit from the

close personal ties available among the “brothers.”

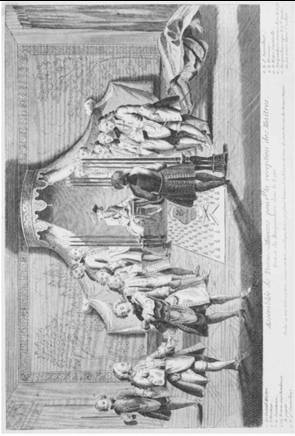

Reception of a Master Mason at a

lodge meeting.

THE SANS-CULOTTES

The term “sans-culotte” referred to the men who did not

wear the short knee trousers (breeches) and silk stockings of the nobility and

the upper bourgeoisie but wore instead the long trousers of workers and

shopkeepers. They were generally from the lower and often impoverished classes,

and “sans-culotte” was originally a derisive appellation. During the

revolution, the sans-culottes became a volatile collection of laborers in Paris

and other cities whose ranks soon included clerks, artisans, shopkeepers,

goldsmiths, bakers, and merchants. They were easily manipulated by popular

leaders such as Marat, Hébert, and Robespierre. The Jacobins used the

sans-culottes to control the streets of Paris and other cities and to intimidate

moderate members of the Assembly. The Committee of Public Safety under

Robespierre was adroit at using the discontented masses, and in September 1793

a decree established a revolutionary sans-culotte army. In October of that

year, this army participated in severe violence and brutality in Lyon against

those it considered enemies of the state. The sans-culottes were associated

with popular politics, especially in the Paris region, and were instrumental in

the September massacres and in the attacks on the Tuileries palace. In January

1794, the sans-culotte army, having served its purpose, was disbanded by the

Terror government.

Militant sans-culottes devoted much of their leisure to

politics, even while holding no official post in their section of the city.

Occasionally they would visit the Jacobin club, but they generally divided

their evenings between the

société sectionnaire

and the General

Assembly. In the section they would be surrounded by friends in their own

social milieu. They wore the red bonnet, the

carmagnole,

and, in

critical situations, carried their pikes in hand. The pike was a powerful

symbol of the people in arms. It was not employed on the front against enemy

armies but was extensively used to quell disturbances at home. When the death

penalty was decreed, on June 25, 1793, for hoarders and speculators, Jacques

Roux said the sans-culottes would execute the decree with their pikes. On

August 1, 1793, the government authorized the municipalities to manufacture

pikes on a grand scale and to provide them to the citizens who lacked firearms.

Besides attending meetings of the

sociétés sectionnaire

s

and the General Assembly, sans-culottes also found time to socialize in

cabarets, cafes, or taverns, where they enjoyed singing patriotic songs.

The life of most sans-culottes was modest. Some bordered on

the fringe of the lower echelons of society and lived in a perpetual state of

desperation. It was not unknown for a family with three or more children to

live in one sparsely furnished room on an upper floor of a building.