Damn His Blood (11 page)

Authors: Peter Moore

Those labourers who remained were faced with new challenges. Successive enclosure acts had been passed in the last decades of the eighteenth century in a bid to make rural England more efficient. The laws carved up the commons, amalgamating the land into large estates – a source of opportunity for ambitious farmers like John Barnett and Thomas Clewes. Oddingley Heath, a vast common to the north of the parish, had already been enclosed by 1791 with villagers stripped of their ancient rights to graze livestock, collect nuts and berries. The move formed part of policy that would see 740,000 acres of open land enclosed between 1760 and 1810. At the beginning of 1806 a bill was passed in Parliament concerning land in Crowle, the adjoining parish. It was another signal that Oddingley’s surviving commons might be next on the list. Reverend Richard Warner, on a tour of the southern counties, mused, ‘Time was when these commons

6

enabled the poor man to support his family, and bring up his children. Here he could turn out his cow and pony, feed his flock of geese, and keep his pig. But the enclosures have deprived him of these advantages.’

In the 1790s uncertainties over land rights mixed with new worries about the rate of inflation. Since the beginning of the French war the British economy had been in an endless state of flux: roaring forward one year only to implode spectacularly the next. The effects were magnified in the countryside, where a fraught population worried about the crops and the cruel caprices of nature. The years 1799, 1800 and 1804 were particularly disastrous for Worcestershire’s farmers, who saw their crops drowned by a succession of devastating rains. In 1802 a hurricane tore across the county, destroying acres of farmland and leading to a fire at the windmill at Kempsey, just south of Worcester, ‘[its] sail being whirled around with such great rapidity’, it was reported. One local chronicler recalled that the new century had broken amid a ‘tempest of war and confusion’.

7

Tensions from the ongoing war seeped into county life too, provoking a change in mindset at local level. In August 1803, with a French invasion increasingly likely, 722 men assembled at Pitchcroft in Worcester and declared themselves the Worcester Volunteers. Over the following months they dragooned the countryside, drawing recruits from every town, village and hamlet. The degree of enthusiasm for the regiment was displayed the following December, when local ladies ‘brought up every particle of flannel that they could lay their hands on, to make flannel dresses [for the men]’. Like the Home Guard of the 1940s, the Volunteers readied themselves for the invaders, marching in nervous enthusiasm from one side of the county to the other. One morning in 1804 the recruits based in Bewdley and Kidderminster were stirred to action, being ‘alarmed very early by the beating of the Volunteer drums, in consequence of reports that the French had landed, 50,000 strong’. It transpired to be another false alarm, but not before they had completed a march of some several miles. They returned, it was dryly reported, ‘in ire and chagrin’.

The volunteers remained in Oddingley’s neighbourhood for several years, serving as a constant reminder of the dangers Britain faced. The population was unsettled: weapons such as pistols, cutlasses and blunderbusses, clubs and bayonets were in ever higher circulation. There were rumours of spies, and strange men with unfamiliar accents were regarded with suspicion. This was the climate in which Parker strove to collect his tax. Worcestershire, like many other counties, was an uptight, uncertain place. As he maintained his policy of collecting his tithe in kind Parker continued to have the support of the law, but he must also have seen the French Revolution as an example of how laws can suddenly change.

From Oddingley Rectory Parker must have watched as these changes swirled through British society. He could not have foreseen any of it. At some pivotal moment in his early life, among the rolling hills and opaque silver skies of the Lake District, he had decided to leave for clerical school in Warwick. To become a clergyman was an admirable rational ambition. He would be a member of the gentry in his own right. Thereafter, a good position would bring him a healthy income, a country residence, a team of servants, a position at the core of his parish and a moral platform to guide the souls of his congregation.

It was a lifestyle that is perfectly portrayed in the pages of Reverend James Woodforde’s diary. Woodforde was a near-contemporary of Parker. He enjoyed a happy life, the majority of it spent at Weston Longville in Norfolk, where he served as the parish parson. Just 20 years Parker’s senior and shielded from the industrial upheavals of the Midlands, Woodforde waged war against nothing more than the toads that infested his pond. He fired his blunderbuss to celebrate King George’s birthday and passed time playing whist or tending to his garden and animals – on one memorable occasion accidentally getting his pigs drunk on strong ale.

In many ways Woodforde’s life was uneventful, but he dutifully recorded his daily routines for more than four decades, documenting with seductive simplicity a benign existence of blithe country walks, occasional sermons and annual holidays, all fuelled by an endless supply of horrifically rich food. This was the archetypal life, the life glamorised by ambitious young curates like George Parker. For Woodforde, living on a generous £400 a year, the tithes were not a divisive tax but an opportunity to knit his community further together. At the end of every year he held a ‘tithe frolic’ to which the ratepayers were invited. The entry in his diary for 30 November 1784 details one of these affairs.

They were all highly pleased

8

with their Entertainment but few dined in the Parlour. They that dined in the Kitchen had no Punch or Wine, but strong Beer and Table Beer, and would not come into the Parlour to have Punch. I gave them for Dinner some Salt Fish, a Leg of Mutton boiled, and Capers, a fine Loin of Beef roasted and plenty of plumb and plain Puddings. They drank in the Parlour 7 bottles of Port Wine and both my large Bowls of Rum Punch, each of which took 2 Bottles of Rum to make.

Woodforde was only separated from Parker by two decades in age and a hundred miles in distance, but his experiences could hardly have been more different. Throughout the second half of the eighteenth century Norfolk remained a gentle backwater of rural England, socially and politically stable and deeply patriotic. In the Midlands 20 years later the industrial towns were not ruled by decaying feudal hierarchies, but by a new elite of diligent, rational men, their mounting fortunes generated by machines and manpower rather than ancient laws and custom. And towns like Birmingham did not just create wealthy industrialists, but served as incubators for the reformist and dissenting movements, both of which attacked the establishment of which Parker was an ingrained and immovable part.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century more and more ratepayers were questioning the right of their clergyman to a tenth of their produce, and with Pitt’s war taxes mounting, tithe disputes and parochial tensions were becoming increasingly common. Parker was far from suffering alone, and there is a striking parallel between his experiences in Oddingley and Reverend John Skinner’s at his parish of Camerton in Somerset. Like Woodforde, Skinner was a diarist, but he differed in almost every other sense. He was meddlesome, irritable and a fierce defender of his rights. For decades he quarrelled with his parishioners, whom he despaired of as insolent creatures. He was ignored, defied and provoked by a hardened group of farmers and labourers, who enraged him by jangling the church bells at night and releasing a screaming peacock beneath his window. A gun was fired at his dog, and when it came to the tithe the farmers were evasive. Once they brought him a broken-back lamb for his share.

Like Parker, Skinner attempted to fight his enemies head on. The results were documented in his diary: stories of petty squabbles in the lanes, sinister goings-on, and the wretchedness of his parishioners, best seen through their drinking and swearing. Skinner became increasingly intolerant with age. He took to distracting himself from the deficiencies of his own life by burying himself in the past. In time he became a noted archaeologist and antiquarian, responsible for excavating many barrows around Camerton, a place that he became convinced was Camulodunum, the capital of the ancient Trinovantes tribe and the most ancient of all Roman settlements in Britain.

This was a faraway, fantasy world to which Skinner clung with all his might. By 1839 he could stand it no longer. An extract taken from the

Bath Chronicle

of 17 October reads, ‘On Friday morning, in a state of derangement,

9

he [Reverend Skinner] shot himself through the head with a pistol, and was dead in an instant.’

Both John Skinner and George Parker were men out of time. Oddingley and Camerton would never be their happy fiefdoms in the same way that Weston Longville had been Woodforde’s. Dreams that had been forged in the late eighteenth century had vanished by the beginning of the nineteenth. As Parker and Skinner stood fast, the sands shifted around them. They had not anticipated the changes: the industrial and political revolutions, wars and inflation. In Oddingley Parker had certainly not bargained on men like Captain Evans, Thomas Clewes and John Barnett – men who would fight him at every step. Parker had arrived at his post to find the rules were changing, that he had been cheated by society of his inheritance and robbed of his dream.

Almost a century after his death, Virginia Woolf still felt a sense of tragic pity for John Skinner and his futile attempts to salvage the souls of his wretched parishioners. It was a fate that Reverend George Parker of Oddingley shared.

Irritable, nervous, apprehensive,

10

he seems to embody, even before the age itself had come into existence, all the strife and unrest of our distracted times. He stands, dressed in the prosaic and unbecoming stocks and pantaloons of the early nineteenth century, at the parting of the ways. Behind him lay order and discipline and all the virtues of the heroic past, but directly he left his study he was faced with drunkenness and immorality; with indiscipline and irreligion; with Methodism and Roman Catholicism; with the Reform Bill and the Catholic Emancipation Act, with a mob clamouring for freedom, with the overthrow of all that was decent and established and right. Tormented and querulous, at the same time conscientious and able, he stands at the parting of the ways, unwilling to yield an inch, unable to concede a point, harsh, peremptory, apprehensive, and without hope.

As Reverend Parker puzzled over the night-time disturbances at his rectory in Oddingley, in London the government was announcing new measures that would all but double the existing property tax and lower the threshold of eligibility. It was a bold move from Lord Grenville’s new administration, which had been formed following Pitt’s death in January and which was being increasingly derided in the press as the ‘Ministry of All the Talents’. The tax increases were roundly criticised, with William Cobbett declaring in the

Political Register

, ‘[it] leaves no man anything in this world

11

that he can call his own’.

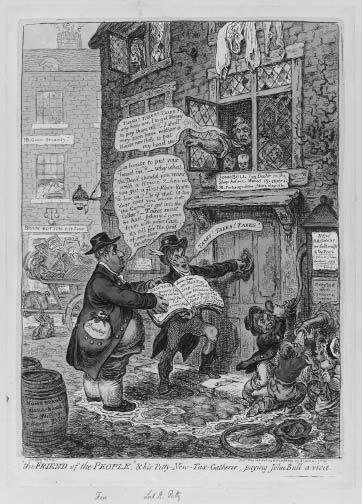

On 28 May James Gillray responded with a satirical caricature that captured the national mood. Entitled

The Friend of the People & His Petty-New-Tax-Gatherer, paying John Bull a Visit

,

12

it lampooned Charles Fox, the foreign secretary, and Lord Henry Petty, the new chancellor of the exchequer. The two men are shown rapping impatiently at John Bull’s door, with Petty bellowing ‘Taxes! Taxes! Taxes!’ as he leans on the knocker. As his furniture is carted away on the street behind, John Bull peeps out of an upstairs window, replying, ‘Taxes? – Why how am I to get Money to pay them all? I shall very soon have neither a House nor a Hole to put my head in.’ The corpulent Charles Fox, supporting a vast folio crammed with a list of new levies, calls up, ‘A house to put your head in? Why what the Devil should you want with a House?’

Published on 28 May 1806, James Gillray’s

A Friend of the People & his Petty-New-Tax-Gatherer, paying John Bull a visit

shows a worn and irritable country

Like much of Gillray’s work the piece was a searing parody, an intoxicating cocktail of lofty satire and burlesque imagery that tapped into a national mood of gathering frustration and captured dissembling politicians like Fox and Petty riding roughshod over popular opinion. The caricature is suggestive of the brittle atmosphere that was pervading England by the end of May. It was a country worn to the bone. The stoic John Bull is depicted embattled in his garret window, about to snap. It is a neat visualisation of the plight of the Oddingley farmers. Not only were they subject to the increased property tax, but they also had to contend with the extra menace of Parker’s tithe. The harvest months now loomed before them, the stones at the rectory window just one harbinger of what was to come.