Damn His Blood (9 page)

Authors: Peter Moore

In the English imagination Napoleon was a lowly creature: effeminate, ostentatious and untrustworthy – the antithesis of John Bull, the gritty, no-nonsense farmer. And as Bonaparte had brought misery to Britain, Parker had brought discord to Oddingley on his arrival in 1793 – the very year war had begun. As the rift between the clergyman and his parishioners deepened, reports began to circle that the farmers met at night in secret locations to curse him and plot their revenge. Drunken oaths were sworn; Parker’s blood was damned.

Their characterisation of Parker, however, was flawed. He had not set out to destroy the existing order in Oddingley, rather re-establish it. He was not a member of the new enlightened classes – an industrialist, a philosopher, a soldier or an explorer – he was a country parson, the very paragon of English tradition and respectability. Of all the parishioners, Captain Evans was the closest to this vision of Napoleon. He was the self-made military man who had risen against the odds to a position of rank, wealth and power.

The nickname may have been unjust, but it stuck. Parker became the outsider – mischievous, antagonistic and ambitious – while, the farmers, led by Evans, were the opposite: free, independent and right. But while the nickname was a powerful social device it did little to help the farmers in the eyes of the law. The most they could do was to make it as difficult as possible for Parker to collect his taxes.

Captain Evans had his cows milked in the adjoining parish of Tibberton in order to avoid the tithe; others hid their goods in hay ricks, barn corners, outhouses and workshops. Villagers were caught in the crossfire, their loyalty split between Parker, their spiritual leader and kindly neighbour, and the farmers who they relied upon to stay above the breadline. Most calculated that it was better not to anger their employers, and the congregations thinned for Sunday service at St James’. One of Thomas Clewes’ workers recalled, ‘None of the family or servants ever frequented Oddingley Church;

26

my master told us he would not order us not to go, that we might go if we like, but he had rather we should stop away.’

It seemed that there was no remedy for the quarrel. By 1805 Parker was employing more and more tithe men, so that he did not have to speak to the farmers himself. One of these recalled how ‘Barnett, Banks and Captain Evans always abused Mr Parker whenever they met him’ and speculated that Thomas Clewes had devised an ingenious strategy to spoil his tithe milk by adding a secret substance to it, causing it to sour as soon as it came from the cow.

That Clewes resorted to skulduggery was possible, but others had less time for such measures and a further incident between Parker and Barnett was more characteristic. Parker had gone to Pound Farm in midsummer 1803 to collect his tithe lamb and met Barnett brooding silently in the fold-yard. Barnett asked Parker which of the animals he would like, and the clergyman responded that Barnett could pick two or three of the lambs out, and from them he would select one. Barnett, exasperated with Parker and livid he was wasting his time, grabbed one of the young animals and thrust it into the parson’s arms, shouting, ‘Take that or you shall not have any one!’ Barnett damned Parker, who fled the fold-yard hurriedly without his lamb. A few weeks later Barnett was prosecuted yet again. The courts were becoming an important check point in a vicious cycle: reaction to Parker, followed by litigation, followed by more reaction – all at an ever-quickening pace.

For the farmers it was an exhausting and futile struggle: they had to submit and Parker was going to make them. Also, after several years it had become clear that they were surrendering far more than £135 a year to Parker by paying in kind. In the autumn of 1805 they backed down and informed Parker that they were willing to pay him £150 a year to compound the tithe and bring an end to the dispute.

The offer satisfied his initial demand, but instead of accepting the proposal outright Parker imposed a precondition to the agreement. Collecting the tithe in kind had been expensive. He had been required to hire staff, to build a tithe barn and fill his tool shed with all the implements of a country farmer. Parker told the farmers that he would only agree to their offer if they paid him £150 in compensation for the inconvenience they had caused.

The farmers were outraged. They had conceded defeat only to be dismissed and embarrassed once again. They flatly refused Parker’s proposal. Only Old Mr Hardcourt and John Perkins remained on speaking terms with the clergyman after this, a fact which annoyed their peers and further split the village. In January 1806 Captain Evans’ frustration at the situation had flared at Perkins. ‘Mr Parker is a very bad man,’ the Captain told him. ‘Nobody in the parish agrees with him.’ When Perkins disagreed, the Captain flew into a rage. ‘Damn him!’ he swore. ‘There is no more harm in shooting him than a mad dog!’

27

This was more than a throwaway curse; it was the unchecked sentiments of an angry and frustrated man. The Captain’s words were redolent with imagery: Parker was a rabid dog – fierce, deranged and unpredictable. Just as a mad hound might fly at an innocent bystander, infecting them with its bite, Parker was doing the same – poisoning Oddingley with his greed, his ambition and ideas.

fn1

Terriers, bulldogs and spaniels were common breeds of hound in the locality, but for guarding property no breed was more efficient than the mastiff, ‘the size of a wolf, very robust in its form and having the sides of the lips pendulous. Its aspect is sullen, its bark loud and terrific.’ (

The London Encyclopedia

, Vol 7. 1824. p.389.)

CHAPTER 3

The Easter Meeting

Tibberton, Worcestershire, 7 April 1806, Easter Monday

GOD SPEED THE Plough was a public house a few paces off the main road at the northern end of the village of Tibberton. It was a small two-storey brick building fitted with neat twin dormer windows nestled into the front of its steep sloping roof. The inn was one of two which served the growing population of Tibberton, a parish a mile to the south-west of Oddingley. Tibberton had a quite different appearance to that of its neighbour. It wasn’t lost amid sprawling hedgerows or fruit orchards, but properly and deliberately arranged about the road which ran through it like an artery, drawing traffic from all the nearby villages as it wended south towards Worcester. A single row of thatched labourers’ cottages lined this route, which on market days teemed with horse-drawn traps, wagons and handcarts, as farmers hauled their goods to market and the drovers urged their stock languidly on.

On the evening of Easter Monday the Oddingley farmers convened at the Plough to celebrate the annual parish dinner. Their own village was too small to support a public house of its own, and Tibberton – with its larger population and busier road – offered the farmers the closest inn of any size. It was now several hours since the argument with Reverend Parker at the vestry, and the farmers’ numbers had swollen, with brothers, local tradesmen and friends joining Captain Evans, the Barnett brothers and Thomas Clewes in the parlour. Among the new arrivals was John Clewes, Thomas’ brother, and George and Henry Banks, who were there at the invitation of Evans. The Captain took the seat at the head of the table – a position which should have been reserved for Parker.

An evening of hard drinking followed. Inns such as the Plough sold ale from wooden casks, wine by the bottle or hogsheads of perry, a pear cider that Robert Southey would encounter two years later on his tour through Worcestershire. ‘Perry is the liquor of this country,’

1

Southey wrote under the extravagant pseudonym Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella. ‘The common sort when drawn from the cask is inferior to the apple juice, but generous perry is truly an excellent beverage. It sparkles in the glass like Champaign, and the people assure me that it had not unfrequently [

sic

] been sold as such in London.’

Alcohol played an important role in village life. Gallons of weak ale or perry were used to sustain the farmers and labourers in summer, during the exhausting harvest shifts, and drinks were exchanged after hours on market days in the alehouses or in farmhouse parlours late at night, when bottles of claret or brandy were fetched up to toast the latest military victory, profitable sale or stroke of luck. All of the Oddingley farmers drank, Thomas Clewes and John Barnett particularly so, and the men were regulars at a long list of local establishments, of which the Red Lion on the Droitwich road was perhaps the most popular. Like many of these, the Plough at Tibberton was divided into a taproom – a stark space fitted with low stools and floored with beaten sand, where the heaviest of the drinking was done from pewter mugs – and the parlour, which catered for a higher class of clientele, who enjoyed such luxuries as carpeted floors, stuffed leather benches and mahogany tables.

In the parlour of the Plough that evening the farmers, almost all of them united against Parker, had a rare chance to share their grievances in an atmosphere that was close and confessional. As there were no women present, there was no one before whom the men had to moderate their drinking, their language or their behaviour. By the time the meal had drawn to a close and the cloth pulled from the table in readiness for the round of toasts, the mood among the farmers was boorish and excitable.

Toasts were an old English tradition,

2

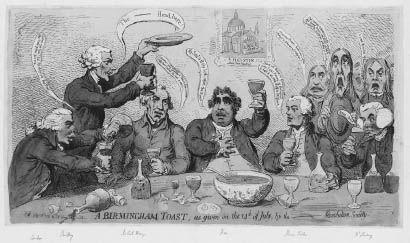

a vital component of any red-blooded dinner party and often loud, enthusiastic and vulgar. It was customary for each diner to stand and toast a gentleman’s name, beginning at the top of society with a member of the royal family and weaving downwards, through a list of landlords and popular local characters, before challenging another member of the table to do the same. Fifteen years before, 18 toasts had been raised at a reformist dinner in Birmingham to celebrate the second anniversary of the storming of the Bastille. The dinner, attended by prominent dissenters and reformists, inadvertently sparked a wave of destructive anti-Jacobin riots in Birmingham; the toasts – to the ‘King and Constitution’, the ‘National Assembly of the Patriots of France’ and to the ‘Rights of Man’ – were perceived as a direct call to arms. The same uneasy passions were present a decade and a half later in Tibberton. In early 1806 patriotic feeling was running high. Nelson’s brilliant but tragic victory at Trafalgar was a fresh and stirring memory, as was the defeat at Austerlitz and the death of William Pitt a month later. The

Gentleman’s Magazine

remembered the age as ‘a time when every newspaper poet,

3

according to his style, exhorted patriots to resist “proud Gallia”, [and urged] John Bull to come on and show his fists’.

As head of the table, it fell to Captain Evans to toast first. It was a practice with which he would have been familiar and he took to his feet charging his glass to the King. Other toasts followed to ‘some noblemen’ and all were returned loudly. At length Evans stood once again and turned towards John Perkins.

For most of the farmers Perkins’ friendship with Reverend Parker amounted to a shameful breach of loyalty, and as a result relations between the farmers had soured. The young farmer had only opted to join the dinner a few hours earlier at the insistence of Parker himself, who, anticipating intemperate words or scenes, had urged him to attend to defend his name. Now Captain Evans seized his opportunity to mock them both, inviting him to drink the health of a

friend

. Perkins refused the invitation, sidestepping the obvious challenge to mention Parker’s name.

The Captain returned Perkins’ stoicism with mockery. He declared Perkins was neglecting his duty to the table and lifted his glass yet again – this time in his left hand – calling out, ‘To the health of the Reverend George Parker!’

James Gillray’s depiction of the infamous Bastille toasts that inadvertently sparked three days’ rioting. Charles Fox toasts with his left hand

‘All drank it but poor Hardcourt and me,’ remembered Perkins.

Not only was the Captain’s toast designed to humiliate, it was an ironic and highly symbolic act. For centuries witchcraft and devilry had been associated with the left hand. It was commonly thought that Satan used the left hand to baptise his followers, that he whispered his commands into the left ear and lingered behind the left shoulder of his followers. The left-handed were maligned accordingly, with shamed mothers demanding that affected children overcome the disability or at least shield it from public view. The poet Walter Savage Landor in his

Imaginary Conversations

wrote, ‘Thou hast some left-handed business

4

in the neighbourhood, no doubt,’ a euphemism that was repeated elsewhere for other dishonest or devious deeds: left-handed favours, left-handed marriages or left-handed alliances. As such, Captain Evans’ toast was laden with imagery. He was openly suggesting Parker was an aberration: left-handed toasts were reserved for enemies, the untrustworthy or sinister.