Damn His Blood (37 page)

Authors: Peter Moore

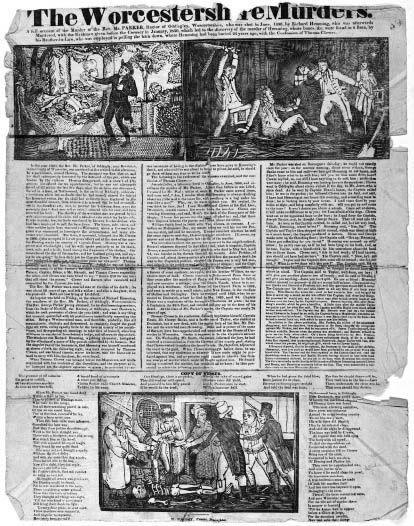

Frontispiece of

The Oddingley Murders

, one of a number of commercial pamphlets to appear in the wake of William Smith’s inquest and Clewes’ confession

Clewes, Banks and Barnett had been incarcerated for a week. Now the verdict had been given, and they had been formally charged, their status changed. They were compelled to don regulation prison dress – yellow velveteen frocks and matching caps – and to undergo the full rigour of the gaol’s regime. This meant rising at a quarter to six, labouring until nine o’clock, and then from ten until one and two to six. The three men were kept apart on different wards.

Although the inquest had ended, the clamour for information persisted. Journalists sought out talkative locals, listened to taproom tales and inferred as much as they could from the suspects’ personal appearances. They penned potted histories of Clewes, Banks, Barnett, Heming, Captain Evans, Reverend Parker and James Taylor, revealing little vignettes as they unearthed them. Their reports were then swapped and syndicated across the country. Captain Evans was the acerbic military man, George Banks a respectable local, John Barnett a wealthy farmer (one newspaper speculated he was worth £20,000), Richard Heming and James Taylor both cast as opportunistic villains, and Thomas Clewes a pitiful character, a prisoner of his past.

They also raked over details of George Parker’s life and stories from the tithe dispute. Some claimed that Parker was the son of the Duke of Norfolk. The

Morning Chronicle

, which had historically opposed the tithing system, published a mischievous article about the Oddingley dispute: ‘In what is anything but unusual [Parker] quarrelled with his parishioners respecting tithes,’ they wrote. ‘Being a Cumberland man,

6

and therefore, probably, like all mountaineers, obstinate and determined, he resolutely fought the good fight till 1806, caring equally little for the love or the enmity of the parishioners, and disregarding all warnings to take care of himself, when one afternoon he was shot at from behind a hedge and afterwards despatched.’

It was unsurprising that the

Morning Chronicle

adopted the case for campaigning purposes, but for other papers the Oddingley affair was most notable for its similarities to a more recent sensation. One newspaper, the

Leicester Chronicle

, was typical of many when it published its account of the inquest under the sub-heading ‘Parallel to the Polstead Murder’. Polstead was a small village in the south of Suffolk which had been thrust into national focus just two years earlier when the remains of Maria Marten, daughter of the village mole catcher, were discovered in a barn. Twenty-five-year-old Marten had disappeared 11 months previously, and had last been seen on her way to meet her companion William Corder at his barn, where her body was later found.

The story had fascinated the country. Corder, who had a bad reputation, had left Polstead soon after Maria’s disappearance. He had told her family they had married and settled on the Isle of Wight. The lie had held for a year, but in April 1828 Maria Marten’s mother began to have strange dreams suggesting that her daughter had been murdered and buried in Corder’s red barn.

7

On 19 April 1828 she persuaded her husband to search the building. ‘[I] put a mole spike down into the floor … and brought up something black, which I smelt and I thought it smelt like decayed flesh,’ Mr Marten told a court several weeks later. It was the decaying remains of his daughter’s body.

The public interest that followed Marten’s discovery had been immense. Corder was traced to London and amid a circus of press coverage was brought back to Suffolk, where he was convicted of murder. Much of the country was caught up in the frenzy. A preacher travelled from London to Suffolk to deliver a sermon to around 2,000 people outside the barn, which now was referred to as

the

Red Barn; Staffordshire pottery figures were produced, and everyone clamoured for a memento. The Red Barn was pulled down and sold as ‘tooth picks, tobacco-stoppers, and snuff boxes’, and after 7,000 people gathered at Bury St Edmunds to watch Corder’s execution the hangman sold sections of the rope at a guinea an inch.

The similarities between the murders were obvious. Both victims had been lured to quiet barns in rural England to be killed by men they knew and trusted. Thereafter their graves were concealed and fictions invented and peddled to those who would miss them. It also seemed odd that both Heming and Marten had been discovered by family members. Was this chance, or providence? But while Maria Marten had been buried for just under a year, Heming had been missing for nearly 24. This fact troubled journalists as much as it excited them. How could those responsible live for so long with such a wicked truth? How could Clewes have continued to live at Netherwood with the skeleton of a murdered man buried just outside his farmhouse? How could Captain Evans have continued to reside in the parish after organising not one but two murders?

It was not unusual for newspapers to speculate on criminal cases. Although the law stated that any publisher could be committed for contempt for distributing articles that prejudiced a trial, in reality few titles took heed of this. The

Worcester Herald

4

did little to cloak its opinions. It reported all Clewes’ statements with gentle cautionary asides, taking every opportunity to remind its readers what type of man he was. Conversely their descriptions of Banks were supportive. The paper judged Banks ‘a fine man of most respectable appearance and of rather pleasing manner’. His reputation was, it confirmed, ‘much esteemed’ in the locality, and it rubbished the suggestion that he was the Captain’s son. One broadsheet, published on Valentine’s Day, went further, brazenly declaring, ‘We trust [Banks] will be able to clear himself from the serious charge brought against him.’ This pamphlet, which ran to more than 30 pages and consisted of newspaper accounts of the depositions, ended with a strangely contradictory paragraph.

In concluding our account

8

of this tragical event, we wish to caution our readers not to prejudge the case against the prisoners, more especially Banks and Barnett; though two atrocious murders have been committed; they may be innocent of participation in them; they still have to be tried by God and their County; may the Jury calmly weigh every fact that has a favourable bearing towards them – and, if innocent – God grant them a true deliverance. Let justice be done at all events.

Press involvement had long tainted the objectivity of legal procedures. In 1828 Justice Gaslee at the Old Bailey had complained, ‘It was much to be lamented that … no case now occurred … which was not forestalled by [accounts in the newspapers] which created a prejudice against accused persons from which it was very difficult, if not impossible, to divest themselves.’ The trial for the Elstree murder

9

in 1823 was notoriously marred by press intrusion. The chief suspect John Thurtell, a frivolous libertine who had killed a fellow gambler after an argument, was falsely accused by

The Times

of having murdered before, and the

Morning Chronicle

managed to refer to all three suspects in the case as ‘the murderers’ before any verdict was reached. The Elstree murder ended up generating so much public attention that two plays telling the story were scheduled for the weeks before the trial. Eventually Thurtell managed to have his trial postponed for a month to allow the excitement to subside, but this did little to improve his chances, and it was said that a crowd of 40,000 watched his execution.

Although the reports of the Oddingley murders did not plunge to such depths, even outside the county the case remained a distracting sensation. Long accounts of the crimes were published in London, Canterbury, Newcastle and Edinburgh, and across the sea in Belfast and Dublin. Each retelling of the story adopted a different slant, attributing the murders variously to the evils of the tithing system, the wickedness of the farmers or the obstinacy of Parker.

In particular, attention was turning to Captain Evans. If Clewes was to be believed, then the Captain was the most culpable of them all. He had organised the opposition to the tithe. He had cursed Parker more violently than anyone else. On Midsummer night Heming had turned to him for protection, and it was on Evans’ orders that he had hidden at Netherwood. On 25 June events had been driven by the Captain, who had improvised, summoning one of his wolfish contacts – James Taylor – to remove Heming for good. How could this behaviour have gone unpunished? How could the Captain have expired peacefully in his own bed, rather than swing from the gallows before the eyes of a pitying crowd?

This puzzle was solved by the growing number of accounts of the Captain’s miserable death. Papers dwelt on the report of sleepless nights, tormented visions and wild furies that characterised Evans’ last days.

Berrow’s

soared to new heights of imagery, evoking the ‘scorpion stings of conscience’

10

and on Saturday 20 February the

Ipswich Journal

added,

Captain Evans, who in May last,

11

passed to ‘that bourne from whence no traveller returns,’ and whose name has been mixed up with the diabolical murders at Oddingley, appears to have been singularly visited with compunctious feelings of conscience, after those acts had been committed. An aged man named Doone, engaged with the monster, after his participation in the crimes, as servant; but such was his turbulent character, such his dread of persons approaching the house, lest apprehension should follow their entry, that ingress was rendered sometimes troublesome, in consequence of the doors and window shutters being kept in a state of closure and bolted; but this fear seems to have somewhat subsided as the case became involved in perpetuity and mystery. These agitated movements, however, plainly betokened that there was something within that harrowed the soul, and held him a felon in his own mind until the day that death ‘marked him as his own’.

More unsettling accounts seeped out into the newspapers. There were reports of neurotic swearing and fervent prayers. At times both Heming and Parker would loom horribly over his bedside as Evans quivered in their shadows below. While Clewes’ suffering had been portrayed through subtle stories of barroom slips, heavy drinking and insomnia, the Captain’s torments were presented in a more dramatic and unnerving way to a readership familiar with the concepts of punishment and atonement. These were not just themes preached from the pulpit but ones that featured heavily in contemporary literature. Mary Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein, a towering literary figure of the day, lamented in a passage which seemed eerily relevant to the Captain’s plight, ‘Memory brought madness with it,

12

and when I thought of what had passed, a real insanity possessed me; sometimes low and despondent, I neither spoke nor looked at anyone, but sat motionless, bewildered by the multitude of miseries that overcame me.’

There are more parallels with Thomas Hood’s ballad

The Dream of Eugene Aram

, which was composed in 1828, just two years before Heming’s bones were discovered. This enormously popular work revisited the story of Eugene Aram, an eighteenth-century schoolmaster and philologist executed in 1759 for the murder of Daniel Clark. Aram had killed Clark 14 years earlier and concealed his body in a shallow grave near Knaresborough in Yorkshire. Aram then left the area and started a new life in King’s Lynn in Norfolk, where he worked at a school as an usher. These are the years in which Hood’s ballad is set, depicting Aram as a kindly, able man with a blackened soul and a terrible secret.

Hood’s Aram is a ‘melancholy man’ detached from the happy society and beautiful countryside that surrounds him. One day Aram comes across a schoolboy reading the story of Cain and Abel. He sits with the boy and begins to talk of Cain ‘And, long since then, of bloody men / Whose deeds tradition saves / Of lonely folks cut off unseen / And hid in sudden graves.’ Aram continues, explaining to the schoolboy,

He told how murderes walk the earth

Beneath the curse of Cain, –

With crimson clouds before their eyes,

And flames about their brain:

For blood has left upon their souls

Its everlasting stain

Did the Captain suffer like Aram? Did he retain the same clear picture of the murder scene? Had Heming’s or even Parker’s blood stained his soul as Daniel Clark’s had stained Aram’s? These misfortunes were all suggested in the newspaper accounts of his death and supported by the testimony of his housekeeper, Catherine Bowkett. But could it be that these accounts were exaggerations? That the Captain suffered no more than any elderly invalid with an iron will and a thirst for life? The stories of frenzied fits might have been influenced by the social and cultural mores of the time. As the Georgian era drew to a close and the Victorian age beckoned, people were becoming more concerned with questions of personal morality, guilt and repentance. Felons like Aram and Evans were expected to suffer, and just as Aram had been mythologised by Thomas Hood, the Captain may have received the same fate at the hands of his housekeeper and the newspapers.