Dancing Barefoot: The Patti Smith Story (29 page)

Read Dancing Barefoot: The Patti Smith Story Online

Authors: Dave Thompson

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Music, #Individual Composer & Musician

Hand on heart, Patti in L.A., 1978.

THERESA K.,

WWW.PUNKTURNS30.COM

I am an American artist. I have no guilt.

THERESA K.,

WWW.PUNKTURNS3O.COM

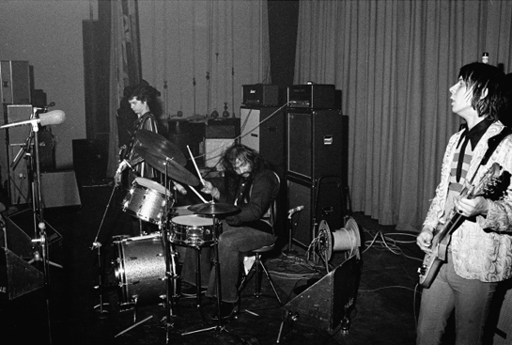

MC5, the original rock ‘n’ roll niggers, outside of society and beyond the law. Guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith (closest to the camera) never truly got over the band’s reputation.

JORGEN ANGEL,

WWW.ANGEL.DK

Patti’s son Jackson, a regular presence alongside her onstage.

THERESA K.,

WWW.PUNKTURNS30.COM

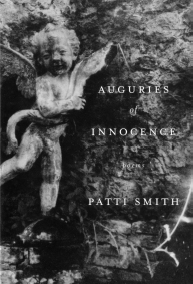

Patti’s most recent book of poetry.

AUTHOR’S COLLECTION

Patti at the Chicago stop of the 2007 Lollapalooza tour.

COURTESY CGAPHOTO, USED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSE (CC BY 2.0).

13

BURNING ROSES

P

ATTI HAD BEEN

working her way up the ladder for close to a decade—longer than that if one wanted to consider the years she spent seeking her identity in the first place. In that time, she had lived as enthusiastically as she could have wished, never pausing for breath or even thinking of doing so. But now she was in her early thirties, in a field that still viewed an artist leaving his or her twenties with uneasy suspicion. The past was behind her. All that mattered was the future, a future that she was building around a change in style, a change in direction, a change in life.

Her late-night telephone conversations with Fred had never been less than passionate. But in the past, it was a passion built around the impracticalities of their present and the dreams they could only glimpse of what might be to come. Not any longer. Now those dreams were in reach, waiting for her at the end of the next record, the next tour.

So why did she still feel ill?

Not ill as in “Get me to the doctor; I think there’s something wrong.” She had passed through those fires the previous year, and only the occasional pain and a drug regimen remained. This sickness was internal.

In part, it may have stemmed from the events of December 9, 1978, when her brother, Todd, was injured in an altercation at Max’s Kansas City. Sid Vicious, the former Sex Pistols bassist, had only recently made bail after being charged with the murder of his American girlfriend Nancy Spungen in October. He propositioned Todd’s girlfriend, and when Todd reacted, Vicious attacked. He smashed a glass in Todd’s face, and as Vicious was arrested again, Patti rushed to the hospital, where doctors fought not only to repair the damage but also to save Todd’s eyesight. His recuperation was long and painful, and nobody could have blamed Patti if her thoughts sometimes seemed to be miles away with her brother. Todd’s scars would clearly mark her work over the next year.

But Patti’s ill mood was about more than that. It was discontent and unhappiness; it was frustration and rage. The commercial success that had enfolded her in the wake of “Because the Night” should not have shaken her as much as it did. But it did, and she wasn’t certain why. Hindsight, ladled liberally onto her career by sundry historians and critics, has attributed Patti’s withdrawal from her original identity first, the entire machine soon after, either to her accident in early 1977, to her move thirteen months later away from the city that shaped her, to the love that drew her from the city, or to the realization that her “career” really did not mean as much to her as she once believed.

In fact, it was all of these things. And it was the knowledge that she had a job to do and an audience to please, and she could not return home until it was finished.

So maybe it was time to finish.

The Patti Smith Group wrapped up 1978 with their now-traditional end-of-year residency at CBGB, three shows that took them up to New Year’s Eve. Just twenty-four hours earlier, John Cale had emerged from over a year’s worth of silence to play the same venue. With a scratch band built around Ritchie Fliegler and Bruce Brody (both veterans of his last live setup), Judy Nylon, and guests Ivan Kral and Jay Dee Daugherty, Cale turned in a short but cataclysmic set that seemed, and might even have been, part improvisation, part sheer brutality, and part mad genius. Nylon’s “Dance of the Seven Veils” might have acknowledged Patti’s influence in its collision of rock and poetics, but it was a savage invocation regardless, while Nylon’s duet with Cale through “Even Cowgirls Get the Blues” was all spectral howls and sibilant whispers.

Ivan Kral was at his best that night—he needed to be. And he was at his best again the following night, when Patti took the same stage. So why did he, and the rest of the band, feel so uneasy?

Maybe it was the speed with which Patti insisted on recording their next LP, knowing full well that they really didn’t have much of anything to record.

Joining the band at Bearsville Studios in upstate New York was keyboard player Richard Sohl, back in his rightful place after a year out of action while he fought illness and exhaustion. Patti also reunited with her former paramour Todd Rundgren, who would produce the new album. His involvement had already been described as the ideal way of recreating the successes of

Easter.

It wasn’t.

“I thought that it would be nice to work with a friend,” Patti told the British magazine

Uncut

in 2004. What’s more, “I knew that he would contribute to the musical sense of the record. He was very good with using keyboards; he was a pianist himself and a lot of those songs evolved around that.” But “it was not an easy record to make.”

The Patti Smith Group arrived at Bearsville in almost total disarray. Not only had they not had the opportunity to rehearse any new material together before the sessions began, but they had scarcely even written any. “They didn’t have material,” Rundgren lamented in John Tobler and Stuart Grundy’s book

The Record Producers.

“But they were committed to doing an album, and they showed up wanting to do one, but not really ready for it…. They left me with the responsibility of trying to turn it into something, and I really didn’t know what to do most of the time. I certainly can’t tell Patti how to make music, but at the same time, it wasn’t as if there was any there ready to be worked with.” If he hadn’t been working with an old friend, he said, the entire situation could have become “very nasty” indeed.

To Patti, the album “was a difficult record to make because we were out of the city, in the middle of winter in Bearsville, pretty much snowed in,” she told

Uncut.

But she already knew, or at least suspected, that it might be the last album she would ever make. “I felt that I had really expressed everything that I knew how to express. So there I had a lot of thoughts doing that record.”

Joyful thoughts and relieved thoughts. The end was in sight.

She handed over a couple of things she had written. “Frederick” was destined to become one of the album’s best-known songs, even before the sessions were complete. But the album’s other jewel, “Dancing Barefoot,” didn’t even exist until the recording was almost over and Rundgren demanded more songs. Kral produced a cassette tape of song ideas that he carried around with him. Rundgren listened and then came back to say which one he wanted them to work up.

And so it was that the last song Kral wrote for the Patti Smith Group was one of the first he had ever written; the riff for “Dancing Barefoot” was one he composed back in Prague when he was thirteen or fourteen years old. Later, Rundgren would single out “Dancing Barefoot” as the song that came together most successfully.

Kral’s gift for melody was visible, too, on two other songs, the hefty “Revenge,” with its Beatles-ish intro, and the punishing semiautobiogra-phy of “Citizen Ship”:

There were tanks all over my city.

They weren’t bad songs, either. Or, at least, they were the closest to what might have eased out of the band in earlier years.

The scrabble for material continued. The poem “Seven Ways of Going” was reprised from so many years before. Later, listeners could extrapolate some kind of warning from its weary prose, Patti

undulating in the lewd impostered night,

before turning

my neck toward home.

But the portentous accompaniment that Rundgren layered around the distinctly straining vocal was a poor match for one of Patti’s most questioning works.

She recorded a cover of the old Byrds’ chest-beater “So You Want to Be (a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star).” She’d first heard it from the artist Ed Hanson back in 1968, and at the time, she’d rebelled against the cynicism that permeates the lyrics, the notion that no matter how high one climbs, the ride is still a painful one. She knew better now.

It would be left to the title track, like that of

Easter,

to truly place the new album in perspective. “Wave” was a hesitant conversation between Patti and a silent interlocutor, while cello, piano, bass, and organ washed around her voice. Haunting and almost hurting, it would become the final track on the LP—and listening to it, one could also take it to be the final song of her career.

Wave to the children / Wave goodbye.