Dark Eminence Catherine De Medici And Her Children (10 page)

Read Dark Eminence Catherine De Medici And Her Children Online

Authors: Marguerite Vance

How could anyone be certain of anything in this life, Catherine wondered, knowing full well that no one could ever be certain of her. The Duke of Guise, so long her feared enemy, was dead at last and there were those who dared say she was responsible for that death.

Then there was Antoine, the conniving weakling who posed a certain threat to her regency. Now Antoine too was dead, so her worries should have lessened materially. But not at all. There was the Prince of Conde, his brother, a man of strong convictions to whom Catherine always had been attracted, but a statesman whom she also feared for the very qualities of shrewd thinking she most admired in him.

Doubtless Conde would lay claim to the regency and this must not happen, for if he did and she defied him, it would mean a dangerous break with the Bourbon House. Catherine

puzzled over the situation for days and then, like a fish swimming toward her through sunny waters, came the answer. The regency should be discontinued! She would declare Charles of legal age to rule though he was only thirteen. He would not dare go counter to her wishes in anything, and as Queen Mother she would in some measure be more apt to bend him to her will than as Regent. The half-mad young King always resented force and as Regent she spoke with the authority of the law; on the other hand, her "advice," more inflexible than any legal mandate, was always obeyed without question. Keep Charles docile, tractable, and the governing of the kingdom was hers until she could place it happily in the hands of her favorite son, Henry of Anjou, a year younger than Charles.

She was very busy, this incredible woman. For one thing, she reminded herself, she must get in touch with that tiresome Jeanne of Navarre who had left the Council of Poissy so abruptly. (Antoine had been an unpardonable boor thrashing young Henry as he had, but Jeanne should have overlooked it. Children survive these things.) She, Catherine, must speak to her about a marriage between Henry and Marguerite. A Navarre-Valois union would be excellent unless—and here another plan suddenly slid into the spectrum of her thinking—unless she could prevail upon Elizabeth to suggest to Philip a match between Don Carlos and Marguerite.

In Spain, Elizabeth had spent five happy years. Physically she was still frail in an exquisite flowerlike way. Scarcely had

she arrived in Madrid when she developed smallpox and came very close to dying. Philip was never far from her bedside, fearless for his own health, absorbed only in the comfort and well-being of the young Queen.

His first marriage, to his cousin, Mary of Portugal, when he was seventeen, had been a very happy one. However, Mary had died when their little son, Don Carlos, was only four days old. Looking at the lumpish infant with its vacant expression and continuous whine, Philip probably guessed the taint the child had inherited from both its maternal and paternal grandparents whose families were equally blighted with insanity. Once sure that his suspicions were correct, Philip lost interest in his son. He turned him over to nurses and tutors and gave most of his attention to an English alliance, his loveless marriage with Mary Tudor, eleven years his senior.

Their wretchedly unhappy marriage ended with Mary's death late in 1558. Now with the lovely Elizabeth his consort, Philip was enjoying some of the happiest years of his life. Courtiers noted that much of his brusqueness had moderated, that his arrogance was less pronounced. He laughed oftener, generously overlooked blunders by inexperienced pages and nervous petitioners. Truly Elizabeth had been well named Princess of Peace.

Fortunately the smallpox left her with only one small blemish on the side of her nose and no one rejoiced more sincerely that she was not disfigured than Don Carlos.

This unhappy youth, smarting still under what he felt was his father's betrayal in marrying Elizabeth whom he had be-

lieved to be his betrothed, fell deeply in love with his young stepmother. Elizabeth, fully aware of the ugly breach between the father and son, simply destroyed the passionate notes Don Carlos wrote her and avoided him as much as possible. But it was not always possible, and again and again only her gentleness and her calm, quiet appeal to his better nature saved her from the madman's advances.

Now to add to her difficulty with Don Carlos, her mother was writing peremptory, trenchant letters insisting that Elizabeth take up with Philip the matter of Don Carlos's marriage with her sister Marguerite. Catherine had put aside all thought of the Navarre marriage from the moment the Haps-burg one occurred to her, and now she wanted the matter settled—at once. "Therefore, my daughter/' she wrote, "do you approach your liege lord, Philip, my son, and put before him this most agreeable matter with all expediency."

Elizabeth opened each of these letters with increasing dread and a growing sense of shock. This was the mother who had warned her about Don Carlos before she came to Spain, the mother in whom she had confided her aversion to and pity for him. How could she possibly consider him a suitable husband for her sister? Perhaps Elizabeth forgot the plans for her own marriage which had included no considerations of the bridegroom's character but only his dynastic prestige among the monarchs of the world. And though she was accustomed to the many lamentable vagaries of royalty, to see her little sister married to the lunatic Don Carlos was unthinkable. In many ways Elizabeth was ahead of her day.

Her answers to her mother s letters were, if not evasive, at

least temporizing: His Majesty was away; His Majesty was not well—a touch of fever; affairs of state made it impossible for her to have a satisfactory talk with him. So ran the Spanish Queen's letters while she tried to summon courage to approach her hushand on the subject she found too distasteful to put into words.

But Catherine was not to be put off. Since she had formally declared Charles of age, her next move must be something to dramatize the fact. A Royal Progress across France would do just that. It would do more, for its terminus would

pg Dark Eminence

be Bayonne, that jewel-like little city on the Spanish border, and here she would invite Philip and Elizabeth to be her guests for a month of feasting, jousts, and masques. Here she could put her plan before Philip, could impress him with her sure knowledge of the fine interdependence between France and Spain, make him her lasting friend. Yes, the Progress had been an inspiration.

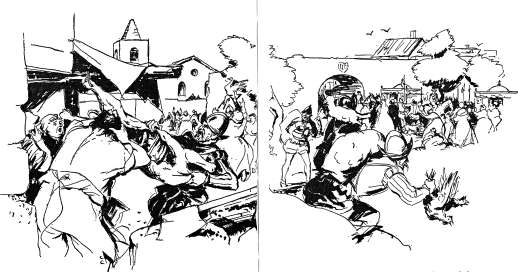

When Catherine undertook anything it was not by half measures, so this masterpiece of pageantry was a dazzling extravaganza which even the Progresses of England's Elizabeth could not equal The cavalcade set out from Saint-Germain in the early spring of 1564. Gentlemen of the Household, grooms, pages, archers, carvers, butlers, falconers, councilors and huntsmen came first, followed by the households of the various members of the royal party. Slowly, banners rippling in the spring breeze, drums and fifes beating out the measure of their tread, the glittering company filed through the stone archway of the palace court,

Charles, the inspiration of it all, knew only that he would be passing through good stag- and boar-hunting country and prayed he would be permitted to try his new spear. His brother Henry and his sister Marguerite had their own thoughts, Henry had not wanted particularly to come. He was just thirteen and something of a poet and took an un-boyish interest in keeping his hands and nails well groomed. Henry would much rather have stayed at home, petting his lap dogs and strumming the new Spanish bandora his mother recently had given him.

As for twelve-year-old Marguerite, between her and her

brother Henry there existed a bond of eerie unity which seemed to stem from unremembered time and isolated them in a strange small world of their own. They enjoyed the same things, reacted identically to all circumstances. Dancing was one of their major delights and it was said that when they entered a tallroom other dancers withdrew to watch their absorbed enjoyment in the graceful passages of the dignified pavane and the romping gaillard. At these times they seemed completely oblivious of everything about them, lost in their concentration on the dance and thek joy in each other. That Catherine should be aware of this strong attachment between the brother and sister was inevitable and with characteristic venom she made her knowledge known to Marguerite, But Marguerite only laughed and shrugged off the fishwifely tirades her mother directed at her in her jealousy—for Catherine would not share Henry's affection with anyone. Nor would anyone ever curb her youngest daughter as she romped through life until at last she died, a dissolute, mountainous woman of sixty-one whose family had cast her off.

The Progress held endless possibilities for Marguerite. Sometimes for a brief mile or so she rode one of the beautiful hackneys her mother imported from Italy, cantering along the line of the procession, ribbons and veilings fluttering out behind her. Again she rode back to the end of the cavalcade where the heavy carts carrying every imaginable sort of equipment lumbered along through the clouds of dust. She found the carters delighted to accept her challenge to banter and fraternize until a gentleman of her household, arriving with orders from the Queen Mother, put an end to the gay inter-

Dark Eminence

lude. Sometimes Marguerite retired to her litter and sang popular songs of the day, accompanying herself on the lute, and not unmindful of the effect of her really fine voice floating back over the mile-long column winding across the hills.

As for Catherine, the genius behind this vast pageant on wheels, she was enjoying herself enormously in spite of the rigors of the journey. She was forty-five years old now and had grown very stout. Saddle horses she rode, and she rode hard and often, were worn out within months and had to be replaced. Though the Progress was virtually a traveling city with its own shops and boutiques where replacements might be made, laces and velvets mended and saddles oiled and polished, one commodity was not to be found among the tons of effects brought for the comfort or entertainment of the company: food. All along the way farmers and small tradesmen saw their stocks swept away by the passing throng, the labor of months lost, yet were helpless to protest. Even so, food on the journey was frequently scant and of inferior quality. Yet Catherine, for all her voracious appetite, never complained and made sure that all had their share.

They traveled east to Bar-le-duc a hundred miles away where Charles acted as godfather to Claude s first baby, a little boy, the future Duke of Lorraine, and Catherine marveled at the miraculous change a happy marriage and motherhood had made in her ugly-duckling daughter. Claude's thin cheeks had filled out, there was laughter on her lips and her eyes, no longer sunken in deep shadows, sparkled with health and happiness.

From Bar-le-duc the company moved east to Troy then

south to Bourg and Lyon. The days grew longer, wanner, then intensely hot. Many of the foot soldiers collapsed in their heavy armor, several died and were buried beside the road. Occasionally when they reached an important town there was a general detraining and a halt of several days while the royal laundry was set up; and meanwhile there were amusing entertainments on the green and Catherine's and Marguerite's dwarfs outdid themselves, tumbling about, singing the bawdy songs of the day, keeping the townspeople in good humor while their stores melted away.

Summer passed and as autumn gales set the curtains of the litters and wagons fluttering, the mountains flung their blue shadows around them. Catherine ordered still another halt while winter clothing, blankets and furs were taken from chests, and forges glowed as horses were sharpshod against the ice and snow ahead.

The Queen Mother gave up riding and retired to her litter. There, buried in furs, she gave herself up to pleasant daydreaming. She had never met her son-in-law, Philip, face to face. In a way she dreaded that meeting in spite of the high hopes she had for it. Philip was a monarch of far-reaching supremacy, an indomitable champion of the Roman Catholic faith. She knew that he was fully aware of her own somewhat tepid devotions and her interest in bringing the Catholic and Protestant faiths closer together—as a matter of expediency—and that undoubtedly he frowned upon it.

Now, and once more because it would further her plans, she must pretend to take a much firmer stand for the Established Church. Marguerite must be presented as a devout