Dark Eminence Catherine De Medici And Her Children (5 page)

Read Dark Eminence Catherine De Medici And Her Children Online

Authors: Marguerite Vance

doubtedly shrugged off the distasteful thought. Impossible young savage, Don Carlos! Hadn't he boxed his ears just recently? Besides, there were still many details to be completed before a betrothal could be achieved. Reports had come to him—actually at Mary's funeral—of the grace and royal bearing of the Princess. Again it had been said more recently that at the marriage of her brother, the Dauphin, she had been acclaimed by those who dared whisper it even more beautiful than the bride! Now Philip must see her or at least know more about her.

Very simply, then, he had his own name substituted in all the lengthy documents drawn up between the Houses of Hapsburg and Valois pertaining to the betrothal of Don Carlos and the Princess Elizabeth. This was in January, 1559. That Don Carlos gave way to a fit of violent rage at his father s consummate audacity was to be expected, but what of Elizabeth?

Though Don Carlos was known to her as rather a sullen boy, someone she had no desire to meet, the name of King Philip, his father, filled her with abject terror. Throughout the length and breadth of Christendom he was known as His Most Catholic Majesty, a monarch who tolerated no slightest liberty of thought in any of his subjects toward the established Church; to question a single tenet of the Church was to light a fagot. He sincerely believed, in a transport of religious zeal, that he was the divinely appointed exterminator of heresy in the civilized world and his dreadful work of extermination was no respecter of age or rank.

His great love was Spain and his contempt for all things

not Spanish roused the indignation of his foreign subjects everywhere. He refused throughout his life to speak or read any language but his own Castilian Spanish. He followed the Spanish fashions in clothing and left the country of his birth only when it was absolutely necessary for political reasons. He was haughty and overbearing, insisting that the electoral princes of his empire, wherever he might encounter them, should remain uncovered in his presence. This was the man Elizabeth presently learned she was to marry.

King Henry, her father, was at one of his smaller palaces in the forest of Compiegne when word was brought him that the Spanish embassy would arrive in Paris early in June (1559) to discuss the betrothal. That allowed only about seven weeks in which to make the vast preparations for the occasion, and Henry set off for Paris at once. Here was a marriage he very much wanted: his favorite daughter to become the bride of the mighty monarch, Philip of Spain. Catherine was overjoyed; she had promised herself that only the best match in the world would do for her beloved Elizabeth. In Philip of Spain she had her answer, and it was with a full heart that she sent for the Princess,

Elizabeth was deep in her Latin grammar when the Queen's page entered the room. The venerable Abb£ de Saint-fitienne sat beside her, watching as she translated the Psalm of her choice, and for a moment he did not realize why his pupil had stopped short in the middle of the line she was reading. Then he looked up and recognized the livery of the Queen's page and sensed the importance of the interruption.

"Yes, my son?"

"Her Majesty, the Queen, would see Madame Elizabeth in the audience chamber/' the boy said. "Her Highness is to come at once/'

He was a blond, ruddy-faced youth and his glance, in spite of his training, touched appreciatively the serene beauty of the girl seated at the table. She was just fourteen, slender, exquisite. Her black hair, tinted a rich gold in conformity with Court custom, was a perfect foil for her dark eyes under delicately penciled brows and for her fair, almost transparent skin. She laid an ivory bookmark between the pages of her Psalter and rose, putting her hand on the Abbe's sleeve.

"Come with me, please, Father/' she said, "as far as the audience chamber only, if you wish/' She suspected what the Queen's summons meant and her hands were suddenly cold.

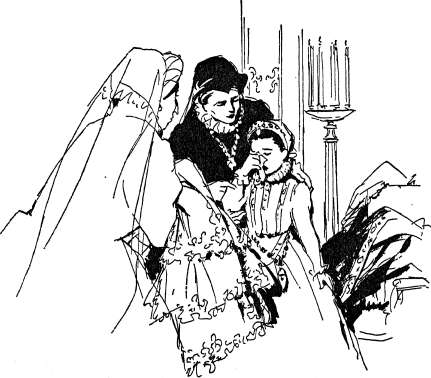

The Abbe left her at the threshold of the audience chamber and she crossed to her mother's side as she had so often seen others do, commanded there by the will of the indomitable woman she loved and feared. Above the noisy pounding of her heart she was conscious of words being spoken while Catherine smiled at her, holding her hand. As though hypnotized, she stared at a medallion of blue enamel set with pearls and hung from a fine gold chain against the bodice of the Queen's gown. She knew something, some acknowledgment was expected of her but her throat was constricted, her mouth dry, and no words would come.

The Queen's fingers tightened around hers and she repeated a question, speaking Italian as she always did when

under stress. "You do understand, Elizabeth, what an exalted position yours will be as Queen of Spain?"

By a final effort Elizabeth managed to steady her voice and her lips sufficiently to answer, "Yes, Your Grace, I understand." She dared not add that everything within her rebelled, that she shrank in paralyzing terror from marriage with a man nineteen years older than she, a man noted for his cruelty, but she could only repeat, "Yes, I do understand."

Chapter 4 TWO BRIDES

THE Queen DaupLiness was enjoying her honeymoon in France among people who made much of her and with a young husband who adored her. Beside Francis she rode along the bridle paths winding through the forest of Blois; from beautiful Diane de Poitiers, with whom she became great friends, she learned the difficult art of tapestry-inaldng; she learned to dance the French dances and to sit straight and firm in the saddle when hunting* (Francis I doubtless would have seen in her a candidate for his "Little Band/*) With unchildlike self-possession she listened without comment when told how four Scottish nobles whom she knew well had been poisoned for refusing to consent to the Dauphin's being made King of Scotland. What Mary Stuart did not understand she refused to dwell upon, though one thing did bother her and for that very reason: she could not fathom

its cause.

Her mother-in-law did not like her and did not disguise the fact. True, Mary recalled having been very rude to the Queen once, but as the Lady Diane so kindly pointed out, that had been forgiven long ago. Majesty never held a grudge, said she. But then, the Queen Dauphiness wondered, what was wrong? She wanted very sincerely to win the regard if not the affection of the Queen and whenever possible she found a place near her in the many Court assemblies, One summer day as she stood quietly at Catherine s side during some minor conference, the Queen asked her rather pointedly why she lingered there instead of pining the other young people out-of-doors on the tennis courts.

Taken aback but with disarming candor Mary answered, 'Tour Majesty, I can always amuse myself with my companions, all to no profit. But in your gracious presence I learn those priceless lessons in deportment which will profit me all my life."

The Queen probably shrugged. This girl who had the bad taste and poor judgment to make a friend and confidant of Diane de Poitiers, a woman old enough to be her grandmother, need expect no encouragement. Besides, jealousy over Mary's first place in the heart of the Dauphin, and the fact that by her presence she automatically lifted the family of Guise into a more exalted position than they had formerly held, did not endear her to Catherine who had been dubious of the marriage in the first place. Only greed for the throne of Scotland for Francis had made it attractive to her. Ambition was the game at which Catherine de Medici played with such furious zeal all her life. At times she seemed to win;

again, as she changed the rules to suit her convenience, she lost; but winning or losing, she never for so much as a day lost her surging interest in the game. At this particular time she prohably was too immersed in plans for Elizabeth's approaching wedding to give her young daughter-in-law more than a passing thought.

Meanwhile there had been another marriage ceremony at Court, a very quiet one which united little Claude of Valois with the Duke of Lorraine. Crippled from birth, Claude was stooped and shrunken, her shoulders and back twisted, and she spent all of her twenty-seven years encased in a series of trusses used in a vain effort to curb the spinal tuberculosis that crippled her. In an age when physical beauty was all-important, Claude's mother looked upon her with frank distaste. How could an advantageous dynastic marriage be expected for a blighted little creature like her? It is remarkable that the little girl did not react differently, but Claude had an unusually sweet nature; and in her sister Elizabeth, two years older, she found a sympathetic companion who showed her love without pity and a warm understanding. The Queen's ambition for Claude was to have her married quickly and out of the way, so when she was not quite twelve she was married to the Duke of Lorraine, a Guise to be sure, but of a minor branch of the House. Ironically enough, little Claude was to be very happy in her marriage and to leave a daughter whom, years later, Catherine adored.

Watching the Duke s knightly attentions to Claude at the wedding feast, Elizabeth was conscious of a twisting ache of rebellion in her own heart. What of the stranger, Philip of

Dark Eminence

Spain? In spite of the extravagant predictions of future splendor, what would life hold for her across the Pyrenees mountains in far-off Spain?

As the weeks passed Elizabeth's terror mounted, and once only a few days before the wedding she buried her face in the shoulder of her beloved governess, Madame de Clermont.

"Why must I go? Why?'' she sobbed. "Wherever I turn I hear His Most Catholic Majesty is harsh and cruel, that he was most unkind to Queen Mary of England, dead but six months. Why does Madame, my mother, think I should

find so much joy in this marriage? Why does the King, my father, speak of my marriage as a tond between the Houses of Hapsburg and Valois? Why?"

Madame de Clermont tucked her own handkerchief under the tear-wet cheek on her shoulder, searching for the right words, the gentle tone to bring comfort.

"Your Grace," she said quietly, 'Trance and Spain have long been at war. Now there is a trace and treaties of peace are being signed. France has lost much, but your marriage to His Majesty, King Philip of Spain, will assure us peace for some years at least—it will heal many wounds. Also, believe not, dear child, that the King is all bad. A man's enemies are quick to give him an evil name and it is not well to believe all the bad one hears. You will be a cherished wife, have no doubts."

Elizabeth dried her tears and made a determined effort to take an interest in the magnificent trousseau being assembled for her. Truly, it was a breath-taking assortment. There were four robes of cloth of gold, another of crimson velvet, two of black velvet, three of white satin, still another of silver damask embroidered in gold thread, to name only a few. "piere were cloaks of fur, others of cloth of silver lined with fur, and mountainous piles of delicate lingerie. It was a trousseau to enchant any bride and Elizabeth did her best to seem appreciative.

With the ladies and gentlemen of her household she paid a visit to the royal stables to inspect the beautiful litter which had been built for her by master craftsmen, and a very bonbon box of a chariot, all rose velvet and lace and cloth of