Dark Mist Rising

Authors: Anna Kendall

Also by Anna Kendall from Gollancz:

Crossing Over

GOLLANCZ

All rights reserved

Not all of them, and not only them. Sometimes an old man could be coaxed into talk, especially if I tripped over him. Occasionally a halfwit who did not know where he was. And twice I have talked to queens. But usually, in the Country of the Dead, it was old women who would come out of their eerie trances to prattle of the lives they had lost, some very long ago. But I was not now in the Country of the Dead. I only dreamed that I was, and the dream was even more terrible than the reality had been.

A flat upland moor, with a round stone house. There is the

taste of roasted meat in my mouth, succulent and greasy. In the

shadows beyond my torch I sense things unseen. Inhuman

things, things I have never met in this land or in that other

beyond the grave. Moving—

'

Peter!'

—

among them is a woman's figure, and the voice coming to

me from the dark is a woman's voice, and I can see the glint of

a jewelled crown. The woman calls my name.

'But—'

'Peter! Wake up!'

'—

you're dead,' I say.

'Eleven years dead,' she says, and gives a laugh that shivers

my bones. And—

'Peter! Now!'

I struck out, blindly, crazed with fear of that monstrous laugh. My fist struck flesh. A cry, and I came fully awake, and Jee lay sprawled against the wall of the sheep shed, his little hand going to the red mark on his cheek.

'Jee! I'm so sorry! Oh, Jee, I didn't mean to ...'

He stared at me reproachfully, saying nothing. Early-morning light spilled through the door he had opened.

The sheep – two ewes and three lambs – stared at me from their bed of straw.

'Jee ...' But what could I say? I had already apologized, and it changed nothing. The blow could not be undone

– like so much else in my life.

'

Eleven years dead

.'

I took Jee in my arms, and he did not resist. Under the fingers of my left hand his bones felt so small. Should a ten-year-old be so small? I didn't know, having so little experience with children. The village children avoid me, frightened perhaps of the stump where my other hand used to be. 'Peter One-Hand', they called me, not knowing how I lost the other, or that my name is not Peter.

Sometimes I think that even Maggie forgets the past.

But I never forget.

Jee freed himself from my clumsy embrace. 'Maggie says ye maun kill a lamb for dinner. The fattest one.'

I blinked. 'Are there travellers?'

'Yes. And their servants. Come!'

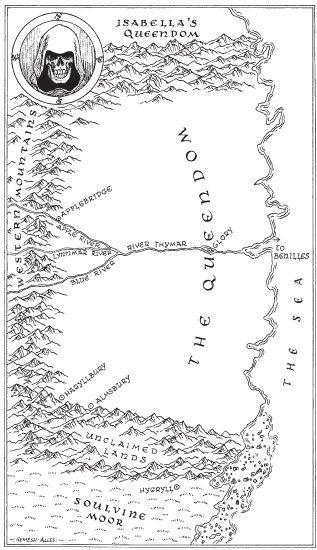

Travellers with servants. Our rough inn, perched above the village of Applebridge in the foothills of the Western Mountains, seldom gets travellers, and never travellers with servants. They must have arrived very early in the morning. I had slept in the sheep shed because two days ago a wolf had carried off Samuel Brown's only lamb, killed it right in the enclosure by his cottage. Maggie had insisted that I build a stout shed, and I had chosen to sleep in it. 'There's no need, it's completely enclosed and has no window,' Maggie had said, her lips tightening.

I hadn't answered. We both knew why I preferred to sleep out here, and that neither of us could bear to discuss it.

I raised myself from the straw, brushed bits of it off my tunic and leggings, and pulled on my boots.

Maggie and I have run this inn for two years. It is due solely to her that we, two seventeen-year-old fugitives and Jee, have been able to make a living. It was Maggie who bartered the last of our coins for the rent on a falling-down cottage in Applebridge. Maggie who hammered and nailed and scrubbed and drove me relentlessly to do the same, until the cottage had a taproom, usable kitchen, and three tiny bedrooms above. Maggie who cooked stews from wild rabbit and kitchen-garden vegetables, stews so good that local farmers began leaving their own cottages to have dinner and sour ale at the inn, talking through the long winter nights and glad for a gathering place to do it. Maggie who bought the ale, driving such a hard bargain that she won the grudging respect of men three times her age. Maggie who acquired our chickens, sewed our tunics, baked and boiled and roasted. Maggie who, just this spring, bought the two ewes from the Widow Moore with our carefully hoarded money. Maggie who had saved my very life, with Mother Chilton's help. I owed Maggie everything.

But I could not give her the one thing she wanted from me. I could not love her. Cecilia stood between us, just as if she had not died. Twice. Cecilia and Queen Caroline and my talent, which I had not used in over two years but which still festered within me, like a sore that would not heal.

The sheep gazed at me meditatively with their silly faces. Stupid animals, they irritated me constantly. They belched, they farted, they got soremouth and ringworm.

They fell on their backs and, when in full wool, couldn't get up without help. They chewed their cud until it was a sloppy wad and then dropped it on my foot. They were afraid of new colours, strange smells and walking in a straight line. They smelled.

Still, I was not looking forward to killing the lamb. One of the ewes lay beside twin lambs, the other nursed a single offspring – which one did Maggie mean by 'fattest'? How many travellers were there, and where did they come from?

I should have been fearful of travellers, but I found I was not. Any change in the small, wearying, unchanging routine of Applebridge was welcome. And there should be nothing to fear: The Queendom had been at peace for two and a half years, ruled by Lord Protector Robert Hopewell for six-year-old Princess Stephanie. No one knew where or who I was. Travellers would be a pleasant break.

'I'm sorry,' I said to the larger and plumper of the twin lambs. It blinked at me and curled closer to its mother.

I left the sheep shed, carefully barring the wooden door, and walked the dirt path to the back of the cottage. The summer morning sparkled fresh and fair. Wild roses bloomed along the lanes, along with daisies and buttercups and bluebells. Birds twittered. The cottage stood on the side of a hill, backed by wooded slopes, and I could see the farms and orchards of Applebridge spread below me, fields and trees all coloured that tender yellow-green that comes but once a year. The river ran swift and blue, spanned by the ancient stone bridge that gave the village its name. Maggie's kitchen garden smelled of mint and lavender.

As I rounded the corner of our cottage to the stable yard, I stopped cold.

'Travellers,' Jee had said, 'and their servants.' But he had not told me of anything like this. Five mules, stronger than donkeys and sturdier than horses, were being groomed and watered by a youth about my own age – although I knew that I, with all that had been done to and by me, looked older than seventeen. The mules were fine animals but looked as if they had been pushed hard to pull the four wagons now drawn off the road. Three of the wagons were farm carts such as everyone used to take crops to market, but they were piled high with polished wooden chests, with expensively carved fur-niture, with barrels and canvas bags. The fourth was a closed caravan with a double harness, such as faire folk use to take their booths around a more populated countryside than ours. This caravan, however, had gilded wheels and brass fittings and silver trim. Neither wagon nor coach, it was a room on wheels, and probably as rich within as without.