Darwin's Island (36 page)

Authors: Steve Jones

Man has flayed his home planet for ten millennia. Soil is hard to make, but easy to destroy. A modern plough shifts hundreds of tons a day, which is beyond the capacity of the most vigorous invertebrate. It digs down to no more than a metre or so, to make a solid and impermeable layer at just the depth of the blades. Another problem arises when fifteen-ton tractors roll across the surface. Their wheels compact the loose soil into a material almost like concrete, in which nothing will grow. In addition, continued ploughing breaks up the topmost layer and allows vast quantities to wash away. Every farm’s raw material is on the move, from hill to plain, from plain to river and from land to sea. The evidence is everywhere. My parents’ house overlooked the Dee Estuary (the Welsh rather than Scottish version). What was, a few centuries ago, a broad waterway has become a green field with a ditch in it and the local council is exercised about what to do about the sand that blows on to its roads. The reason lies in the fertile fields of Cheshire and North Wales. They have been ploughed again and again and their goodness has disappeared downstream.

The process is speeding up. The amount of organic carbon in Britain’s lakes and streams has rocketed in the past twenty years and in some places has almost doubled. Waters that once ran clear now flow with the colour of whisky, which itself gains its hue from the carbon-rich streams that run through peat bogs to feed the stills. On the global scale, matters are even worse. Twenty-four billion tons of the planet’s skin are washed away each year - four tons for every man and woman - and although some is replaced and some has always been lost to the rain and to gravity, the figure is far higher than once it was.

Man has long been careless of the deposits in his soil bank. Again and again, as a civilisation grows it empties its underground accounts, goes into decline and collapses. Usually it takes around a thousand years. Marx himself noticed, for he wrote: ‘Capitalistic agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil.’

Darwin compared the work of the worms with that of the plough. Since his day, farm machines have become far more powerful. His experiments showed how earth could slip and churn, but he had no more than primitive tools to measure how much movement there now is. A sinister spin-off of modern technology has come to the aid of science. From the first atom bomb in Nevada in 1945 to the last air-burst of a hydrogen bomb in 1968, vast quantities of radioactive fallout spilled across the world. Radioactive caesium, which has a half-life of around thirty years, binds to soil particles. In an undisturbed site, the element is most abundant near the surface, but after a plough has passed the radioactivity is dispersed to the depth of its blade. As the disturbed ground is washed away, the irradiated soil is lost, to accumulate in places where the mud settles. In the Quantock Hills of Somerset, soil is, in this era of industrial agriculture, lost at around a millimetre every year. As the land sinks, the ploughs dig deeper, and the relics of the Romans that lie beneath will be smashed within a century - although, thanks to the worms, they have been preserved for two thousand years. Already, most of the treasures picked up by metal detectors come from ploughed fields, proof of how fast man’s machines are stripping the fragile surface of the globe.

The Romans themselves paid the price for their abuse of the soil, for at the time of their decline and fall so much damage had been done to Italy’s farmlands that a large part of the Empire’s food had to be imported. The fertile fields around their capital lost their goodness and vast quantities of grain were shipped in from Libya, which in turn became a wasteland as its surface was stripped by ploughs. In Rome’s last Imperial years, it took ten times more Italian ground to feed a single citizen than it had during its heyday.

The damage had begun long before. The first large towns appeared in the Middle East around eight thousand years ago. Quite soon their growing populations began to demand more food. The farmers exploited their precious mould with no thought of replacing its goodness or allowing their fields to rest. Instead they attacked it with ceaseless vigour. The plough was invented soon after oxen were domesticated. In a few centuries the topsoil was gone and many villages were abandoned. Within a couple of millennia, all the fertile land of Mesopotamia was under cultivation. Many irrigation canals were built. The soil was soon washed away, and the canals became blocked with mud. Enslaved peoples such as the Israelites were forced to clear it (and the abandoned city of Babylon is still surrounded by dykes of earth ten metres high, the remnants of their labours). Abraham’s birthplace, Ur of the Chaldees, once a port, is now nearly two hundred and fifty kilometres from the sea, and the plain upon which it sits is the remnants of what were fine fields, lost to leave a desert. Salt poisoned the last of the land, and what had been the Fertile Crescent - and the civilisation it fed - collapsed.

The same happened in China, where the Great River was renamed the Yellow River two thousand years ago as swirling earth changed the colour of the water. The ancient Greeks, too, faced the problem when the country around Athens was stripped bare. Plato blamed the farmers.

The real disaster for the skin of the Earth came in the Americas. The Maya bled their landscape dry, as did the inhabitants of Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde - the abandoned Native American settlements that now form part of the deserts of the American south-west. The Europeans were even worse. Virginia’s ‘lusty soyle’ was ideal for tobacco, but the plant sucks goodness from the ground as much as it does from the bodies of those who consume it. In three or four years of that hungry crop the soil was drained of goodness, but farmers saw no need for fertiliser (‘They take but little Care to recruit the old Fields with Dung’) and simply moved on to the next piece of land. George Washington himself complained that exhaustion of the soil would drive the Americans west, as it soon did. Charles Lyell, Darwin’s geological mentor, used the huge gullies that scarred the devastated surface of Alabama and Georgia to examine the rocks below and commented that soon American agriculture would collapse.

The nemesis for vegetable mould - and a major threat to our own future - began in 1838 when John Deere invented the polished steel plough - ‘The Plow that Broke the Plains’, as the memorial at his childhood home calls it. Soon thousands of his devices were tearing up the prairies.

Since farmers began to work the Great Plains, the soil has lost half its organic matter. The Mississippi is what Mark Twain called America’s ‘Great Sewer’, and the amount of silt that pours down it has doubled since John Deere’s day. As the crew of the

Beagle

had noticed

,

yet more is taken by the wind. A thin layer of sod had kept the prairie soil in place and soon it began to blow away. The Dust Bowl followed. A huge gale in May 1934 blew a third of a billion tons of dust eastwards from Montana, Wyoming and the Dakotas. The dense cloud reached New York two days later, and petered out far out in the Atlantic. The finest material was blown furthest, which meant that the New Englanders gained the nutriment-filled dust that had passed through the guts of Montana worms, while the unfortunate westerners were left with just a rough and hungry silt. The gales returned again and again until by the mid-1930s more than a million hectares of prairie had been replaced by desert.

Beagle

had noticed

,

yet more is taken by the wind. A thin layer of sod had kept the prairie soil in place and soon it began to blow away. The Dust Bowl followed. A huge gale in May 1934 blew a third of a billion tons of dust eastwards from Montana, Wyoming and the Dakotas. The dense cloud reached New York two days later, and petered out far out in the Atlantic. The finest material was blown furthest, which meant that the New Englanders gained the nutriment-filled dust that had passed through the guts of Montana worms, while the unfortunate westerners were left with just a rough and hungry silt. The gales returned again and again until by the mid-1930s more than a million hectares of prairie had been replaced by desert.

The situation elsewhere is worse. Worldwide, an area larger than the United States and Canada combined has already been despoiled. In Haiti, almost all the forest has gone and thousands of hectares of ground are now bare rock. Less than a quarter of the island’s rice, its staple food, is now home-grown and over the past decade food production per head has gone down by a third. In China, the Great Leap Forward exhorted the peasants to ‘Destroy Forests, Open Wastelands!’ They did, and the soil paid the price. A parallel problem in Africa explains some of the continent’s chronic instability. Across that landmass, three-quarters of the usable land has been bled of its nutriment by farmers, who cannot afford fertiliser and whose fields are, as a result, no more than a third as productive as those elsewhere. Its earth still leaches its goodness into the water, or into dust. The Sahel, the area of thin soil to the south of the Sahara, is becoming a dust bowl and loses two centimetres of surface each year. Hundreds of millions of people go hungry as a result. A planet ploughed by man is far less sustainable than it was when tilled by Nature.

In 1937, after the Dust Bowl disaster, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said in a letter to state governors that ‘The nation that destroys its soil destroys itself.’ His Universal Soil Conservation Law became the first step to putting right the damage done to the precious fabric of his nation. It promoted careful ploughing, the use of windbreaks and a ban on the reckless destruction of forests. Within a few years, most of the American Dustbowl returned to a semblance of health. To plough with the contours, rather than against them, makes a real difference (and the Phoenicians had the same idea). In China, too, the Three Norths project plans a five-thousand-kilometre strip of trees in an attempt to stop the light earth from being taken by the wind. Even the Sahel has gained hope from low technology, with lines of stones set across the slopes to stop the thin earth from washing away. In Niger alone, fifty thousand square kilometres of land have been put back into cultivation.

Soil protection of this kind has a long and unexpected history. In most of the Amazon basin, the soil is bitter and thin for constant rain leaches goodness away, and the vegetation feeds on itself as it recycles nutrition from its own dead logs (which is why cleared forests are so infertile). Patches of the so-called Terra Preta (‘black soil’) lands, in contrast, are small islands of deep dark earth scattered among those starved soils. They were formed not long after the birth of Christ by native peoples who settled down, fed slow fires with rubbish and leaves, piled up excrement and added bones to the mix. They lived in large and scattered cities that recycled their rubbish and set up, in effect, precursors of the green belt that surrounds many modern towns. Over the centuries carbon levels shot up and the ground became filled with worms and their helpful friends. They chew up the ashes and excrete it as a muddy paste of carbon mixed with mucus. So fertile is terra preta, with ten times the average amount of nitrogen and phosphorus, that it is now sold to gardeners.

In Amazonia, the United States and elsewhere, the worm has begun to turn, although perhaps too late. The new concern for the soil is manifest in many ways. Organic gardeners use ‘vermicompost’ - the end-product of species such as the red wriggler fed with waste from farms or factories - as a powerful boost to the garden. Real enthusiasts make their own in bins into which they throw household rubbish and old newspapers to be transformed into fertiliser. They are part of a global movement which sees commercial agriculture of the kind that destroyed the prairies as an enemy and tries, in a small way, to replace what has been lost.

On the larger scale, too, the ploughman is going out of fashion and the burrowers and their fellows are allowed to work undisturbed. Farmers now scatter seed on undisturbed ground, or insert it through the previous year’s stubble. The world has a hundred million hectares of such ‘no-till’ agriculture, and even in places where the plough still rules, the land is treated with more care than before. Brazil, in particular, with its deep ant-built landscapes, has been a pioneer. No-till farming does its best to leave the hard work to Nature. Instead of clearing the ground of dried stalks or leaves, the remains of a crop are left behind. They are soon dragged underground. As a result the earth can take up more carbon and become more fertile. Weeds are suppressed by the mat of dead vegetation that appears, water runs away more slowly and the temperature of the surface is less variable, and better for planted seeds, than in a bare ploughed field. Farmers who once saw worms as a pest now realise that to let them flourish undisturbed does more to preserve the ground - and to make profits - than to use machines.

The move away from technology and the return to Nature’s tillers has been a real success. In some places it reduces soil loss by fifty times, and the habit is spreading fast. In Canada, two-thirds of the crops now grow on earth left unploughed, or ploughed in such a way as to reduce the damage. An era in which millions of tons of mud are lost from fields may be succeeded by an age in which plants and animals - their efforts feeble as individuals, but all-powerful en masse - are allowed to regenerate the soil. Darwin, with his passion for the natural world, would be pleased; but there is still a lot to be done. The risk of a global Mesopotamia - a collapse in food production as the worms’ precious but forgotten products are squandered - has not gone away.

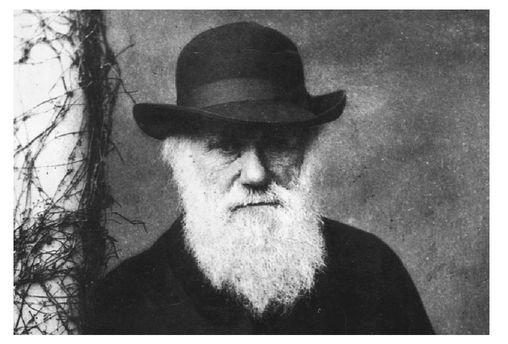

The great naturalist himself, in old age, often spoke of joining his favourite animals in ‘the sweetest place on earth’, the graveyard at Downe. He was denied the chance to offer himself to their mercies for he was interred in Westminster Abbey, whose foundations kept them out. His remains may have been saved from the annelids but have no doubt been consumed by other creatures. Darwin’s simple idea - of the importance of gradual change in forming the Earth and all that lives upon it - has replaced the power of belief with that of science. Perhaps today’s science of the soil will return the compliment by allowing worms and their fellows to restore the damage done by his descendants to their most important product: the vegetable mould that keeps us all alive.

ENVOI THE DARWIN ARCHIPELAGO

Other books

The Journey Prize Stories 28 by Kate Cayley

Amanda Scott by Madcap Marchioness

The Secret Brokers by Weis, Alexandrea

Stalked by Death (Touch of Death) by Hashway, Kelly

Dangerous to Kiss by Elizabeth Thornton

Speedboat by RENATA ADLER

One Night in Mississippi by Craig Shreve

Goldsmith's Row by Sheila Bishop

Fatal Truth: Shadow Force International by Misty Evans

Why Women Have Sex by Cindy M. Meston, David M. Buss