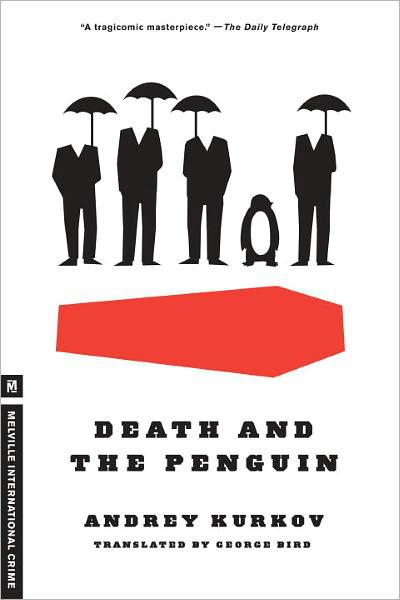

Death and the Penguin

Read Death and the Penguin Online

Authors: Andrey Kurkov

‘A brilliant satirical take on life in modern-day Kiev. Watch out, though, as Kurkov’s writing style is addictive’

Punch

‘Darkly comical thrillers are what we look forward to from the writers of the former USSR, and Ukrainian Kurkov conjures up both Gogol and Dostoevsky in a conspiracy laden plot … Genuinely original’

Scotsman

‘Wistful but (thankfully) not whimsical. Funny, alarming, and, in a Slavic way, not unlike early Pinter’

Kirkus Reviews

‘For all the air of menace, Kurkov keeps the tone light and the pace brisk in this marvellously entertaining and yet sobering work’

Age

, Melbourne

‘An original and sinister satire of chaotic, post-Soviet Ukraine … moving, thrilling and intelligent’

What’s On

Kurkov’s novel exists in an all-encompassing vacuum that, like a kind of narrative narcotic, insinuates itself into the reader’s pores until what was once surreal has achieved its own normality … Kurkov is a strangely entrancing writer’

Booklist

‘A successfully brooding novel, which creates an enduring sense of dismay and strangeness’

Times Literary Supplement

Death and the Penguin

Originally published in Russian as

Smert’postoronnego

by the Alterpress, Kiev, 1996

First published in Great Britain by The Harvill Press, 2001

Copyright © 1996 by Andrej Kurkov and 1999 Diogenes Verlag, AG, Zürich, Switzerland

Translation © George Bird, 2001

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

eISBN: 978-1-61219-076-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011925819

v3.1

FOR THE SHARPS,

IN GRATITUDE

A Militia major is driving along when he sees a militiaman standing with a penguin.

“Take him to the zoo,” he orders.

Some time later the same major is driving along when he sees the militiaman still with the penguin.

“What have you been doing?” he asks. “I said take him to the zoo.”

“We’ve been to the zoo, Comrade Major,” says the militiaman, “and the circus. And now we’re

going

to the pictures.”

| Viktor Alekseyevich Zolotaryov | a writer |

| Misha | his penguin |

| Igor Lvovich, the Chief | an editor |

| Sergey Fischbein-Stepanenko | militiaman |

| Nina | his niece |

| Misha-non-penguin | an associate of the Chief |

| Sonya | his daughter |

| Sergey Chekalin | “friend” of Misha-non-penguin |

| Stepan Yakovlevich Pidpaly | a penguinologist |

| Lyosha | a guard |

| Ilya Semyonovich | a vet |

| Valentin Ivanovich | Chairman, Antarctic Committee |

| Fat Man | |

First, a stone landed a metre from Viktor’s foot. He glanced back. Two louts stood grinning, one of whom stooped, picked up another from a section of broken cobble, and bowled it at him skittler-fashion. Viktor made off at something approaching a racing walk and rounded the corner, telling himself the main thing was not to run. He paused outside his block, glancing up at the hanging clock: 9.00. Not a sound. No one about. He went in, now no longer afraid. They found life dull, ordinary people, now that entertainment was beyond their means. So they bowled cobbles.

As he turned on the kitchen light, it went off again. They had cut the power, just like that. And in the darkness he became aware of the unhurried footfalls of Misha the penguin.

Misha had appeared

chez

Viktor a year before, when the zoo was giving hungry animals away to anyone able to feed them. Viktor had gone along and returned with a king penguin. Abandoned by his girlfriend the week before, he had been feeling lonely. But Misha had brought his own kind of loneliness, and the result was now two complementary lonelinesses, creating an impression more of interdependence than of amity.

Unearthing a candle, he lit it and stood it on the table in an empty mayonnaise pot. The poetic insouciance of the tiny light sent him to look, in the semi-darkness, for pen and paper. He sat

down at the table with the paper between him and the candle; paper asking to be written on. Had he been a poet, rhyme would have raced across the white. But he wasn’t. He was trapped in a rut between journalism and meagre scraps of prose. Short stories were the best he could do. Very short, too short to make a living from, even if he got paid for them.

A shot rang out.

Darting to the window, Viktor pressed his face to the glass. Nothing. He returned to his sheet of paper. Already he had thought up a story around that shot. A single side was all it took; no more, no less. And as his latest short short story drew to its tragic close, the power came back on and the ceiling bulb blazed. Blowing out the candle, he fetched coley from the freezer for Misha’s bowl.

Next morning, when he had typed his latest short short story and taken leave of Misha, Viktor set off for the offices of a new fat newspaper that generously published anything, from a cooking recipe to a review of post-Soviet theatre. He knew the Editor, having occasionally drunk with him, and been driven home by his driver afterwards.

The Editor received him with a smile and a slap on the shoulder, told his secretary to make coffee, and there and then gave Viktor’s offering a professional read.

“No, old friend,” he said eventually. “Don’t take it amiss, but it’s no go. Needs a spot more gore, or a kinky love angle. Get

it into your head that

sensation

’s the essence of a newspaper short story.”

Viktor left, without waiting for coffee.

A short step away were the offices of

Capital News

, where, lacking editorial access, he looked in on the Arts section.

“Literature’s not actually what we publish,” the elderly Assistant Editor informed him amiably. “But leave it with me. Anything’s possible. It might get in on a Friday. You know – for balance. If there’s a glut of bad news, readers look for something neutral. I’ll read it.”

Ridding himself of Viktor by handing him his card, the little old man returned to his paper-piled desk. At which point it dawned on Viktor that he had not actually been asked in. The whole exchange had been conducted in the doorway.

Two days later the phone rang.

“

Capital News

. Sorry to trouble you,” said a crisp, clear female voice. “I have the Editor-in-Chief on the line.”

The receiver changed hands.

“Viktor Alekseyevich?” a man’s voice enquired. “Couldn’t pop in today, could you? Or are you busy?”

“No,” said Viktor.

“I’ll send a car. Blue

Zhiguli

. Just let me have your address.”

Viktor did, and with a “Bye, then,” the Editor-in-Chief rang off without giving his name.

Selecting a shirt from the wardrobe, Viktor wondered if it

was to do with his story. Hardly … What was his story to them? Still, what the hell!

The driver of the blue

Zhiguli

parked at the entrance was deferential. He it was who conducted Viktor to the Editor-in-Chief.

“I’m Igor Lvovich,” he said, extending a hand. “Glad to meet you.”

He looked more like an aged athlete than a man of the Press. And maybe that’s how it was, except that his eyes betrayed a hint of irony born more of intellect and education than lengthy sessions in a gym.

“Have a seat. Spot of cognac?” He accompanied these words with a lordly wave of the hand.

“I’d prefer coffee, if I may,” said Viktor, settling into a leather armchair facing the vast executive desk.

“Two coffees,” the Editor-in-Chief said, picking up the phone. “Do you know,” he resumed amiably, “we’d only recently been talking about you, and yesterday in came our Assistant Arts Editor, Boris Leonardovich, with your little story. ‘Get an eyeful of this,’ said he. I did, and it’s good. And then it came to me

why

we’d been talking about you, and I thought we should meet.”

Viktor nodded politely. Igor Lvovich paused and smiled.

“Viktor Alekseyevich,” he resumed, “how about working for us?”

“Writing what?” asked Viktor, secretly alarmed at the prospect of a fresh spell of journalistic hard labour.

Igor Lvovich was on the point of explaining when the secretary came in with their coffee and a bowl of sugar on a tray, and he held his breath until she had gone.

“This is highly confidential,” he said. “What we’re after is a gifted obituarist, master of the succinct. Snappy, pithy, way-out

stuff’s the idea. You with me?” He looked hopefully at Viktor.

“Sit in an office, you mean, and wait for deaths?” Viktor asked warily, as if fearing to hear as much confirmed.

“No, of course not! Far more interesting and responsible than that! What you’d have to do is create, from scratch, an index of

obelisk jobs –

as we call obituaries – to include deputies and gangsters, down to the cultural scene – that sort of person – while they’re still alive. But what I want is the dead written about as they’ve never been written about before. And your story tells me you’re the man.”