Defiance (13 page)

Authors: Tom Behan

Looking back many years later Peppino’s mother recognised that the best thing she could have done was to leave her husband. Yet back in those days this was far easier said than done, particularly for a woman of her generation: ‘Who would have helped me?’ she wondered, rightly raising the prospect of being a social outcast if she left her husband. The cultural set-up back then was that as a mother and wife Felicia had duties on both levels, she belonged to others and could not make a decision independently of them, especially one that would destroy the conventional family structure.

Despite all of this, Felicia was a very modern woman. Another woman who was fast becoming a fixture in the household – Giovanni’s girlfriend Felicetta – was surprised at the openness of this woman forty years her senior:

When I first started coming to this house what struck me was that she read a lot of newspapers – there were always five or six on the table – which Peppino had bought. Given that she was on her own a lot she would read them as well. Giovanni was off working with his father, whereas Peppino was upstairs studying. Then he would come downstairs and leave the papers on the table.

Felicia was old-fashioned and modern at the same time. I think she got a lot of this from Peppino, whereas Peppino got his character from her – strong and decisive. He also got his subtle irony from her too.

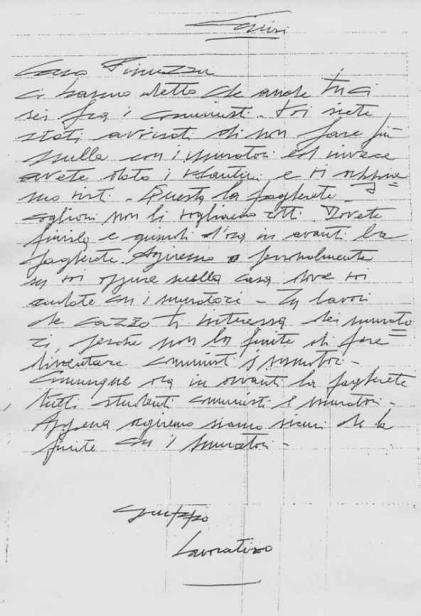

By now it wasn’t just Peppino’s newspaper articles and speeches that were annoying the Mafia. He would frequently make very precise accusations about the links between

Mafiosi

and local politicians – clearly somebody was giving him inside information. It’s never been clear who passed these details over to him. Pino Vitale, another campaigner in the same group thinks: ‘it could have been a cousin – Stefano Impastato – who was mayor for a while. He didn’t agree with his other Christian Democrat councillors, so he might have had a reason to give him information. But Peppino never revealed who his informant was, because if it became known then the source would have dried up.’ Another definite source were the anonymous letters he often received.

Much of this activity was often just background noise for Peppino’s father. But, as Felicia says: ‘Sometimes things were calm at home. But during election campaigns arguments used to break out.’ Locally Peppino was growing in stature; some people might still disagree with him, but many others now listened to what he said. This was a worry for politicians concerned that their Mafia links might be made public. And all of this got back to her husband Luigi: ‘As soon as he heard that Peppino and his friends were organising a meeting he got angry,’ but this wasn’t just because of what his eldest son was doing: ‘he wanted Giovanni to keep his distance from Peppino. But I’d tell him: “Giovanni should go with this brother, he should be by his side.” That’s what I wanted.’ Luigi wanted the opposite, for Peppino to work in his shop, alongside his brother Giovanni, in the hope of keeping him out of trouble – but Peppino wasn’t interested.

Giovanni was starting to identify with his elder brother: ‘We always felt that my father had made a choice to become a slave to the power of the Mafia – our choices were liberation and democracy.’ But Peppino was far beyond Giovanni’s position and this created problems between them, as he openly admits:

I was younger and I was afraid. I didn’t agree with his method of clashing with the Mafia head-on. But in some ways I was jealous of him, also because for good or bad all attention was focused on him. So automatically I was excluded, almost ignored, and this was a burden for me. We used to argue frequently, and sometimes we even came to blows.

Sometimes family tensions exploded in public, such as the evening that a new open-air pizzeria was opened at the side of the Impastato family shop, when a group of Peppino’s friends decided to play some music to celebrate. One of them, Giovanni Riccobono, remembers: ‘I was operating the lights. Something must have happened between him and Giovanni, because at a certain point Peppino starting grabbing bottles and throwing them in the bushes.’ Salvo Vitale, who was playing bass guitar, adds, ‘Then he stormed off in a foul mood. I never found out why.’

Not only was Giovanni trying to deal with an older and highly strung brother, but, as he said, there was also the fear that arose from his awareness of the Mafia’s power: ‘

Mafiosi

used to go regularly to council meetings to check on what was happening. They would often go to Christian Democrat public meetings too.’ Naturally they didn’t take part in the debate, they just wanted everyone to see that they were there, keeping an eye on everyone. Because Giovanni wasn’t rushing around writing leaflets, organising meetings and giving speeches, he had more time to observe what was going on. He was largely outside the intensely political atmosphere of Peppino’s group, and perhaps he could gauge the opinions of ordinary local people better, who after all were his customers day after day at the family shop.

Giovanni used to see policemen and

Mafiosi

: ‘walking down the street together as friends. They often went into a bar for a coffee together. There was a

carabiniere

colonel in Terrasini, Lombardo, who was always hanging around with them. You used to see this all over town, a very direct relationship between the Mafia and the police.’ The strength of the Mafia doesn’t just lie in their ability to kill people; if they can create a situation where they also control the police and politicians then people lose all hope in democracy and justice, and just become more and more scared.

Even though Felicia agreed with Peppino’s stance, she was getting increasingly worried: ‘I used to say to him – “you’re a dead man. Don’t keep making trouble.” I often went upstairs to his room and jumbled everything up, creating a big mess.’ All this tension even produced a chink of humanity in her husband, who told her: ‘Get him to stop. Tell him to stop. He’s digging his own grave, that’s what he’s doing.’ He only said this to her alone, at night, so as not to lose face in front of his children. The possibility of actually losing his son had occurred to him, and for the first time he started to grapple with his conflicting loyalties towards his son and his Mafia friends.

For Felicia, her husband’s shift made her blood run cold: ‘at night in bed I’d grind everything over in my mind’. She obviously wasn’t upset about her husband talking to her, searching to find a way for his son to reduce his ‘exposure’. But what her husband had told her confirmed something that had been preying on her mind: ‘That’s how I knew they were talking about it’ – ‘it’ being murdering Peppino.

Unlike many other countries, setting up a radio station in Italy is fairly easy – access is not denied on the spurious grounds of a lack of waveband space, or the payment of expensive licence fees to the authorities. And back in the 1970s, in the last few years before television became the dominant media, young activists made ample use of ‘free’ radio stations. The first ever ‘free’ radio was set up by the civil rights campaigner Danilo Dolci in Partinico in March 1970, a man whose activities had impressed Peppino and others a few years earlier. This Radio of the New Resistance only lasted a couple of days before it was closed down by police, but the issues it brought out, the authorities’ lack of support for people who had suffered in an earthquake in 1968, created a national debate.

Five years later another attempt was made, using Danilo Dolci’s transmitter, but on this occasion Radio Free Wave lasted for several years. The driving force behind it was Gino Scasso, who had been at the centre of the 1968 student movement at Milan’s Cattolica University, before moving back to his hometown of Partinico and being elected as a far left councillor in 1970. Perhaps one of the reasons it lasted so long, as he explains, was because: ‘it wasn’t just a militant radio station because we didn’t have a group of activists prepared to dedicate themselves to that alone. So there were a lot of request shows and some serious music programmes that played jazz.’ Scasso also remembers: ‘Peppino used to come to the studio sometimes’; they had been at high school together in Partinico a few years earlier. Always open to new ideas, Peppino got involved: ‘I can remember one particular story I followed with Peppino, a young woman from a very poor family, mentally disabled, who had been abducted from Cinisi station and raped.’ The mushrooming of these revolutionary radio stations was so widespread that the transmitter that activists from Cinisi were to use came from a failed experiment that had only lasted a few months in the nearby town of Castellammare del Golfo.

above

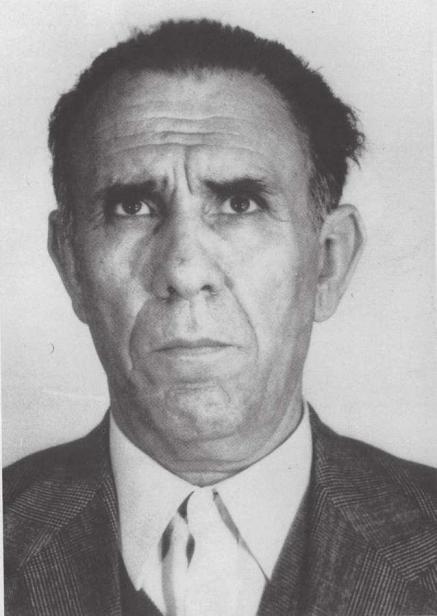

above2

‘Don Tano’ – Gaetano Badalamenti

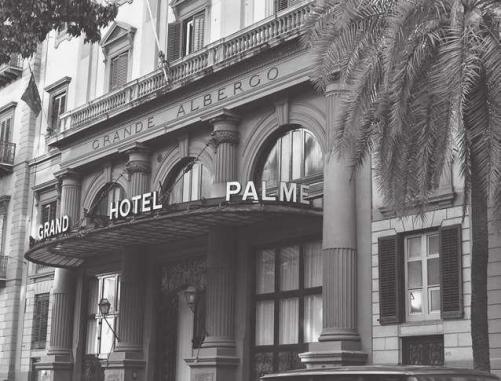

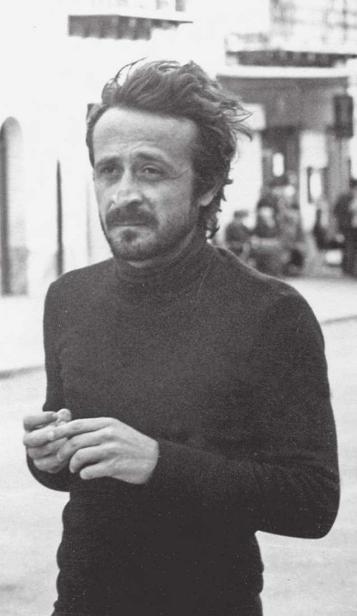

facing page, from top

3

Hotel Delle Palme

4

Felicia Impastato