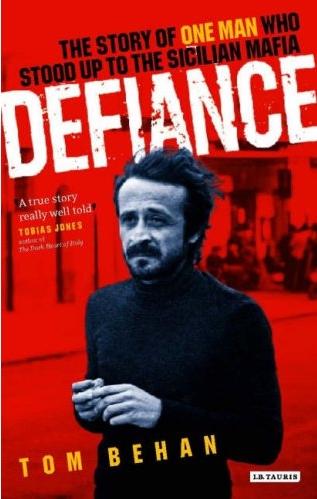

Defiance

Authors: Tom Behan

The Story of One Man Who Stood Up to the Sicilian Mafia

The Story of One Man Who Stood Up to the Sicilian MafiaTom Behan

Published in 2008 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com

In the United States of America and Canada

distributed by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

The right of Tom Behan to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, eletronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the proior written permission of the publisher.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Typeset by JCS Publishing Services Ltd, www.jcs-publishing.co.uk Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

List of Illustrations vii

1

Two Deaths 1

2

The Killing Fields 4

3

Hotel Delle Palme 15

4

The Man Who Made Leaves Move 27

5

It’s in the Air that You Breathe 35

6

The Impastatos 50

7

Welcome to Mafiopoli 67

8

Bulldozers, Builders and Brothers 80

9

Capo

of the Commission 99

10

Crazy Waves 109

11

The Last Crazy Wave 130

12

And the Windows Stayed Shut 138

13

The Light Behind the Blinds 155

14

The Bells of St Fara 179

Afterword 193

Bibliography 203

Acknowledgements 209

Index 211

Illustrations appear between pages 120 and 121

1

Cinisi, showing the motorway, the main street (the Corso), the airport and the sea

2

‘Don Tano’ – Gaetano Badalamenti

3

Hotel Delle Palme

4

Felicia Impastato

5

Peppino Impastato

6

Threatening letter sent to local activists

7

A meeting of the Music and Culture group

8

Front blinds of the Impastato house

9

Giovanni Impastato

10

A funeral in Cinisi

11

A house confiscated from the Badalamenti family, with Mount Pecoraro in the background

12

A funeral procession on Cinisi’s main street

1

Two Deaths

he driver of the midnight train from Palermo stopped the locomotive when he felt a bump on the line. He climbed down and saw the rail was twisted and

broken, but luckily the train hadn’t jumped the tracks. It was 1978 and nobody had mobile phones. So he stopped at the next station, Cinisi, where he told the stationmaster what had happened. Oddly, the police were only contacted two hours later.

When they searched the area they quickly saw that about two feet of the track had been destroyed in what looked like an explosion. But the blast hadn’t just damaged a stretch of railway line. As the police report written later that morning stated:

A body had been blown to pieces and fragments were spread over a radius of 300 metres. They are described as follows: a piece of the cerebral lobe, bones from the vault of the skull and segments of scalp were all found at a short distance . . . A piece of bone identified as a segment of the spine . . . there are loose pieces of tissue everywhere whose original bodily position cannot be identified . . . a limb, presumably the right thigh-bone . . . partly covered Defiance

About 100 metres from this bone the remains of the left thigh-bone were discovered . . . spread all around the area, particularly close to the railway line, were fragments of clothing made up of two patterns: a green, brown and grey check; blue material probably belonging to the trousers; blue wool probably belonging to a jumper . . . Furthermore, on the road-bed adjacent to the line two Dr. Scholl clogs were found . . .

While the police were writing their report, another murder took place in Rome. Three men took their hostage down into a garage and shot him repeatedly. They then drove the body to the city centre and left the car, phoning the press with the news. This murder was carried out by the Red Brigades, a left-wing terrorist organisation. The man they had killed was Aldo Moro, whom they had kidnapped 55 days earlier. Moro had been elected as Italy’s Christian Democrat prime minister five times, and was arguably the most powerful politician in the country – this is why the Red Brigades kidnapped him. They hoped to gain credibility by negotiating the release of some of their members held in jail in exchange for Moro, or alternatively to obtain large amounts of money through payment of a ransom. When it became clear the government wouldn’t negotiate, they killed him. So after a month and a half of anguish, with the Pope even offering to substitute himself as hostage, the huge public crisis came to a tragic end.

Naturally there was wall-to-wall television coverage of Moro’s death, so the other death earlier that day in Cinisi didn’t make it onto television news, and newspapers only commented on it briefly the next day. After all, this was a sleepy town whose only notable feature was the fact that Palermo airport had been built within its boundaries. What apparently connected the two deaths was terrorism; the police quickly said the dead man in Sicily was probably a

left-wing terrorist who had been blown up by his own bomb. But what really connected them, or rather what connected Aldo Moro and national politics to the body blown to pieces in a small Sicilian town was the Mafia.

The Killing Fields

hen three American tanks drove into the central Sicilian town of Villalba on 20 July 1943, the soldiers immediately asked local people to

call Don Calogero Vizzini for them. Eight days later US Lieutenant Beehr from the Allies’ civil affairs office presided over a ceremony at the local police station, in which Vizzini became mayor of his home town.

The Allied invasion of Sicily in the summer of 1943 overthrew a dictatorship that had lasted twenty years. Their problem was that opposition to Mussolini and fascism was dominated by Socialists and Communists, whose demands hardly coincided with American plans for postwar Italy. Rather than working with these mass democratic organisations, the Allies turned to a different kind of power structure.

Superficially, Vizzini seemed a very respectable middleaged man, two of his brothers were priests and one of his uncles was a bishop. But a quick look at Vizzini’s criminal record during the fascist period illustrated what kind of man he really was: tried for four different murders he had been acquitted each time, although he was convicted of Mafia membership and spent five years in jail. He had also been charged, but not brought to trial, for 39 murders, six attempted murders, 36 robberies, 37 thefts and 63 extortions. Documents written by US agents at the time clearly show that officials knew who the Mafia leaders were – indeed Vizzini was probably the leader of the Mafia at the time – they therefore had no objection to giving political power to top

Mafiosi

.

A similar event occurred in the town of Mussomeli, just a few miles away. A new councillor, Giuseppe Genco Russo, had been acquitted of five murders in 1928, four in 1929 and three in 1930, together with three attempted murders; in 1931 he escaped conviction for being a member of a criminal organisation, and in 1932 once again was acquitted of three murders. However, he was convicted of conspiracy to commit a crime in 1932 and served three years of a sixyear sentence.

These appointments were being supervised by Colonel Charles Poletti, the senior allied adminstrator of Occupied Italy. An American businessman from an Italian background, he had been deputy governor of New York State before the war and was also a Freemason. Naturally, Poletti appointed specialised staff, such as his interpreter Vito Genovese, to help him. Apart from being fluent in two languages Genovese had a long criminal record, given the fact he was one of the main bosses of the US Mafia – indeed he had fled New York in 1936 to escape several charges of murder.

Whereas for the Allies reliance on the Mafia meant keeping Communists and Socialists at bay, for the Mafia it meant making large amounts of money. The economy of an area in which a war has just been fought is always in need of emergency supplies, and a huge quantity of Allied goods went missing. Some researchers have estimated that up to 60 per cent of goods unloaded in Naples during this period ended up on the black market.

So, for many Sicilians, the removal of Mussolini also meant the resurgence of the Mafia, which had found new fertile ground given both the poverty and difficulties people faced during and immediately after the war, and the tolerant attitude of the Allies. Although the reality of the Allies’ formal support for democracy was far murkier than it seemed, it nevertheless gave many poor Sicilians the space they needed to resume the battle for social justice that fascism had repressed twenty years earlier.

With the end of Mussolini’s repressive regime and the hardships of wartime, the deep frustration and impatience many people felt for radical change sometimes took on extreme forms, and produced equally uncompromising responses. In October 1944, when council workers went on strike in Palermo against abuses in the rationing system, troops began firing and throwing hand grenades into the crowd, killing 30 people and wounding 150. Between December 1944 and January 1945 there were a whole series of revolts in Sicilian towns, generally lasting only a day or two. One of the more violent, which raged for a week, took place in the far south-east, in the town of Ragusa, and broke out when call-up papers arrived. Young people didn’t want to join the army – some had already fought in Mussolini’s fascist army. The entire town rose up in armed rebellion, using their own weapons and what the German army had left behind. The fighting went on for several days and at least 37 were killed and 86 wounded.

By now the war was far away, the remnants of Mussolini’s regime and Nazi invaders were being fought in the north of Italy, and would finally be defeated in April 1945. The big issue throughout Sicily was now land reform. Half of all of Sicily’s agricultural land was owned by just 1 per cent of the population, huge swathes of land had often been left uncultivated – in the midst of masses of hungry and unemployed peasants. The new democratic government in Rome, made up of all the anti-fascist parties but closely monitored by the Allies, faced a choice: either try and repress this movement even further, or head it off by giving it limited powers and accepting some of its demands, while all the time promising ‘jam tomorrow’ as regards the big political and economic issues.

The government’s most important concession came on the central issue of land reform, when it passed a law that broke up the

latifondo

, the large private estates. Peasants could either work the land and for the first time keep much of the produce for themselves, or the land itself would be redistributed to local cooperatives – a key development as it encouraged peasants no longer just to think of their own family but in collective or class terms. Furthermore, most of these cooperatives were controlled by the Communist and Socialist parties. In many areas of the Sicilian countryside, for the first time in many decades, local people looked forward to a brighter future.

All of this was deeply worrying for the local establishment, as such reforms damaged their long-established interests. Feudalism – a system under which large landowners were legally entitled to have their own private armies and dispense ‘justice’ on their own terms – had officially been abolished in Sicily barely a hundred years before. The origins of the Mafia can be traced to the end of feudalism, with the first recorded mention of the word occurring in the 1860s. The first

Mafiosi

evolved from the people who enforced the landowners’ contract, or wishes, over these large tracts of land where the owner himself rarely – if ever – set foot. In an island where the new national state of Italy had very little presence, these first

Mafiosi

were armed rent collectors. But when peasants became radical and organised, and began making demands, in effect these early

Mafiosi

acted as the military wing of the owners of these big landed estates of the interior.

The proposed redistribution of land meant that large landowners were facing a huge loss in wealth and power. In reality, just one hectare in ten was actually handed over to peasants, given that local magistrates made the final decision and often rejected peasant requests on technicalities. Alternatively, the police intervened to discourage peasants and trade unionists deliberately. In one notorious incident in San Giuseppe Jato a police commander forbade the text of the land reform law from being displayed in trade union offices, claiming it would lead to disorder.

Nevertheless, the peasants’ newfound organisation and confidence were so high that they often simply marched onto land and occupied it anyway, regardless of whether it was fully legal or not. With trumpets blaring, hundreds and sometimes thousands formed up into a procession with their horses and tools to take the land. Often children were at the front of the march, and the local church had an organised presence too; so as well as the red flags of Communists and Socialists sometimes there were white flags with crosses. Behind the children came the women, then the town band, then peasants on horses or mules, or on foot. Behind them the artisans (cobblers, basket-weavers, barbers) and students. Schools were often shut down for the day of the occupation: whole towns would turn out, in what became a festival with two high points – crossing the boundary into the estate, and planting the crops that would be harvested in the months to come.

Meanwhile, the big landowners and their Mafia henchmen were not the kind of people to take this sort of thing lying down. In Sicily it was one thing to pass a law and quite another to apply it. As one

Mafioso

once told a peasant: ‘The law! You’ve stuffed your heads full of this law. Round here, we’re the law, we’ve always been the law.’ The first victim of the Mafia’s campaign to intimidate left-wing peasants – and stop them legally occupying large tracts of land – was Andrea Raia, who was murdered near Palermo in August 1944. The following month the leader of Sicilian Communists, Girolamo Li Causi, went to give a speech in Villalba, the hometown of the Mafia’s leader, Don Calogero Vizzini. First Vizzini’s brother, the parish priest, tried to drown out Li Causi by ringing the church bells. Li Causi continued, and when he started talking about the land and the links between

Mafiosi

and big landowners Vizzini cried out: ‘It’s not true.’ This was the signal for a coordinated attack on the meeting: Vizzini’s nephew and town mayor threw a hand grenade, while other

Mafiosi

started shooting. Fourteen Communists and Socialists were wounded, including Li Causi. The next significant murder followed in June 1945, the victim was a trade unionist; another was gunned down in September, a man who had been fighting to gain control over one of the Mafia’s prime assets – freshwater wells, a vital resource in such a dry climate.

In December the secretary of a local Communist Party branch was murdered. Given that nearly all of these crimes went unpunished, either due to the authorities colluding with the Mafia or eyewitnesses not wanting to testify, the Mafia naturally grew in confidence and raised its sights the following year. So in May 1946 it was the turn of the Socialist mayor of Favara, who had been elected two months earlier with a huge majority. The following month the Socialist mayor of another nearby town, Naro, was also killed by a shotgun blast as he rode through the countryside.

Aware that the murder of individuals and mayors had not been enough, the Mafia now moved on to attack whole groups; after all, land occupations were carried out by large numbers of peasants. So in September, when a group of peasants were holding an evening meeting to discuss how to organise the occupation of Prince San Vincenzo’s estate, local

Mafiosi

who had traditionally guarded the prince’s estate threw a bomb into the room, killing two men and wounding 13.

In April 1947, four days before the crucial vote for the new Sicilian regional parliament, at Piana degli Albanesi, the house of a local Communist councillor was attacked with two hand grenades. In the town at the other end of the Portella della Ginestra pass, San Giuseppe Jato, ‘Death to Communists’ was painted on the front doors of many people taking part in the election campaign.

Throughout Sicily the traditional ruling class was grappling with what democracy meant after twenty years of fascism. On 25 February and 30 March 1947 waves and waves of peasants descended on the Sicilian capital, demanding land reform. Palermo had never before seen such numbers of peasants, who arrived by train, bus or even on horseback in their tens of thousands.

The key hurdle for all players was the first democratic election for the Sicilian regional parliament, due to be held on 20 April. After the onslaught they had carried out in the countryside, landowners,

Mafiosi

, magistrates and the police must have thought the peasants had stopped revolting. A new party called the Christian Democrats, supported by the Church, seemed sure to win. But the result sent shock waves around the entire country: the joint Socialist–Communist ticket won 29 seats, and the Christian Democrats just 19. In reality, because the Christian Democrats were a new party – having been formed just five years earlier – powerful forces such as the Vatican, the White House and Italian industrialists had still been wary about throwing their weight fully behind them.

Much of the local establishment were prepared to back a movement for the independence of Sicily, committed ‘to end the exploitation of Sicily by the mainland’. It was financed by big landowners, who hoped that poor people would be attracted to it out of a sense of Sicilian nationalism, thus isolating them from the class-based appeal of socialism and communism. The leaders of this movement for autonomy held at least one meeting with Mafia leader Don Calogero Vizzini, which also included an Italian general. A report was written up by the US consul in Palermo, Alfred Nester, showing once again the US government’s intimate knowledge of the Mafia. Nester’s letter, classified ‘secret’ and sent to the secretary of state in Washington, began thus: ‘I have the honor to report that on November 18, 1944 General Giuseppe Castellano, together with Mafia leaders including Calogero Vizzini conferred with Virgilio Nasi, head of the well-known Nasi family in Trapani and asked him to take over the leadership of a Mafia-backed movement for Sicilian autonomy.’

Over the next few years big landowners increasingly turned to Salvatore Giuliano’s bandit gang. Giuliano’s criminal career had begun with him going on the run in 1943 aged just 20, after he had murdered a policeman who caught him with a black-market consignment of wheat. In the lawless climate of those years, the notion of living up in the mountains as part of a gang of bandits was tempting to significant numbers of desperate peasants. Giuliano’s gang quickly showed itself to be the most ruthless and successful, killing dozens of policemen during repeated attempts to capture him; it has been estimated his gang was responsible for an incredible 430 murders. He was an efficient killer, who ended up in a game far bigger than himself, manipulated by landowners and shady members of the police and secret services. As his deputy Gaspare Pisciotta said at a trial a few years later: ‘We are a single body – bandits, police and Mafia – like the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.’