Delivered from Evil: True Stories of Ordinary People Who Faced Monstrous Mass Killers and Survived (28 page)

Authors: Ron Franscell

Tags: #True Crime

He was making one last effort to penetrate her when he suddenly looked up and listened intently. He had heard something he didn’t expect: a car in the driveway.

Dianne watched him as he leaped up, dressed, and grabbed her purse and cordless phone. Frustrated at being interrupted—at losing control of the situation—he stomped Dianne hard in the stomach and fled out the back just as her son Herman came in the front door.

Dianne was numb and barely conscious. She felt no pain, just relief.

She was alive.

Herman had come home for lunch to find a strange car parked in his spot in the driveway. He noticed a gold-colored Mitsubishi Mirage with front-end damage and a front license plate advertising a local dealer, Hampton Motors. It belonged to nobody he knew.

He went inside, and everything was quiet until he heard his mother’s distressed voice in the living room.

“Help!” she cried. “Get a knife!”

Dianne was splayed on the bloody rug, delirious, with her skirt pulled up around her waist. Her face was badly bruised and her eyes were swollen shut. Then Herman saw the back door swinging open and ran outside to see the gold Mirage speeding away down Highway 31, with a silvery cord hanging from a rear window. He ran back inside, got his keys, and peeled out of the driveway to chase the man who attacked his mother, but he quickly lost sight of him.

When he returned to the mobile home, he followed a trail of blood to find his mother, who had stumbled into the bedroom, called 911, and passed out.

When detectives arrived, they found Herman waiting for them in the driveway, furious. His fury was so intense he couldn’t describe what he’d seen.

Dianne was Life Flighted to Lafayette General, where doctors found she had a skull fracture; many cuts and bruises around her neck, face, and scalp; and other injuries to the back of her head. They were unable to collect any of the attacker’s DNA. Over the next five days in the hospital, while police scoured her home for clues, an investigator gently worked through the details with her and asked her to describe her assailant for a police sketch artist.

The next day, St. Martin’s Parish cops released a composite sketch of Dianne’s would-be rapist and a description of his gold Mitsubishi sedan.

What they didn’t know at the time was that they were releasing the first public portrait of a serial killer. It never crossed their minds that this crime in little Cecilia could be related to a recent series of killings in Baton Rouge.

And they didn’t know that Dianne Alexander was his first and only living victim. All the rest were dead. And there would be more.

THE WRONG PROFILE

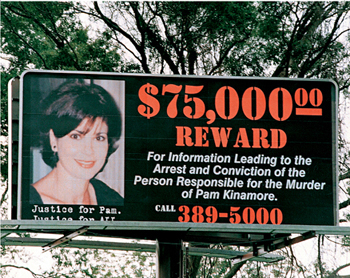

Three days later, on July 12, Pam Kinamore, a forty-four-year-old mother and antique-store owner, disappeared from her Baton Rouge home one evening. Her nude, rotting corpse was found four days later under a swampland bridge 30 miles (48 kilometers) west of Baton Rouge, nearly decapitated by three vicious slashes across her throat. She had been raped.

The body, exposed to humid Louisiana summer heat and various bayou predators, was unidentifiable except for a gold wedding band on its left ring finger. It was Pam Kinamore’s. But her husband noticed that the body was not wearing Pam’s favorite thin silver toe ring.

BATON ROUGE POLICE HOPED A 2002 BILLBOARD OFFERING A REWARD FOR INFORMATION WOULD HELP THEM FIND A SUSPECTED SERIAL KILLER TERRORIZING THE AREA, BUT THEIR INVESTIGATION WAS HAMPERED BY SEVERAL WRONG TURNS.

Getty Images

Police also found a strand of phone cord near the body and collected it as evidence.

The medical examiner determined Pam had been alive when her throat was cut because there was blood in her lungs.

Two witnesses reported seeing a white pickup truck driven by a white man with a naked, frightened, white female passenger matching Kinamore’s description on the night she disappeared. Other than the DNA collected from her body, that was all the local cops had to go on.

White man. White pickup truck.

Within two weeks, police announced that trace DNA evidence conclusively linked the murder of Kinamore, a one-time beauty queen, to the same man who had killed at least two other local women in the past year: Gina Wilson Green, a forty-one-year-old nursing supervisor found strangled in September 2001; and Charlotte Murray Pace, a twenty-two-year-old grad student whose throat was slashed in a townhouse near the Louisiana State University campus the previous May.

News of a serial killer among them stunned the citizens of Baton Rouge, and a flood of questions were only starting to be asked—but not answered very well.

Like Kinamore, the two earlier victims were attractive white women with chestnut hair, and there had been no forced entry into any of their homes. But that’s where the common characteristics ended.

Pace and Green both drove BMWs, but not Kinamore. Pace and Green both jogged on the same lakeside path near LSU, but not Kinamore. Pace and Green had lived a few doors from each other on the capital’s Stanford Avenue, but Kinamore didn’t live nearby. Green and Kinamore both loved antiques, but not Pace. Green and Kinamore were both older, petite women; Pace was tall and young.

WITHOUT REMORSE

Less than a month after Kinamore’s slaying, the Baton Rouge Multi-Agency Homicide Task Force was formed to find the serial killer, but it released precious little valuable information to the public, even though police agencies in the greater Baton Rouge area had more than sixty unsolved cases of missing or murdered women since 1985.

The task force lacked credibility almost from the start. The streets of the state capital were already alive with rumors, complicating the investigation. Scuttlebutt pegged the killer as a professor at LSU, a BMW salesman, or a cop. It said he played tapes of crying babies outside so women would open their doors. The police themselves fueled the hysteria by telling the frightened citizens of Baton Rouge the killer was a white man driving a white pickup.

Pride played a role, too. When criminologist Robert Keppel, an investigator credited with catching Ted Bundy and Gary Ridgway, the Green River killer, offered to help the Baton Rouge task force, it declined.

Women swarmed to self-defense classes and started carrying guns. Every white guy in a white pickup got suspicious looks from passing motorists and pedestrians.

Task force members wanted to bet on statistics. They put their faith in the tendencies of serial killers to use the same methods, stalk identical kinds of victims, and avoid crossing racial borders.

So the task force also dismissed other possibly related cases brought to them by other cops. The January stabbing of white, brunette Geralyn DeSoto was ignored because she had not been raped, her wounds were not as vicious, and the murder happened in West Baton Rouge, a decidedly different jurisdiction. Besides, her husband was the prime suspect in that crime.

Nobody had yet studied the DNA of human tissue found beneath Geralyn’s fingernails, or they would have known that she, too, was killed by the same man.

FBI profiler Mary Ellen O’Toole built a portrait of the killer. She said he was likely between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-five. He was big and strong,

weighing up to 175 pounds (97 kilograms). His shoe size was between 10 and 11. He earned an average wage or less—money was tight—and he probably didn’t deal with the public in his job.

He blended into the community and was seen as harmless. When he lost control of a situation, he regressed to primitive anger. And he blamed other people when he lost control.

He hadn’t expected Pam Kinamore’s body to be found, O’Toole surmised, so he might have gone back to the crime scene to see where he screwed up.

When Dianne Alexander’s composite sketch

was shared with Baton rouge cops, they

dismissed it because her would-be rapist was

black and drove a Mitsubishi. Their killer

was a white man driving a white pickup.

Going deeper into his psychology, O’Toole said the killer stalked his victims, who were likely to be attractive women of a higher social class. He might even have chatted with them before his attacks. He wanted to be appealing, but he was too unsophisticated to truly relate to them.

He likely gave odd, unexpected gifts to the women in his life, possibly even “trophies” he’d taken from victims. He didn’t handle rejection well but was cool under pressure. Because he chose high-risk targets at high-risk times of day, he liked the excitement of the attack. Despite his planning, he was impulsive. In relationships, he was hot-tempered and irritable. He was, like most serial killers, without remorse or empathy. Worse, the killer was learning from his mistakes and evolving. And as time wore on, he was likely to become increasingly paranoid.

She didn’t say whether he was white or black. But whether the police had watched too many TV crime shows or their suspicions had been influenced by witnesses who swore they saw a white man in a white truck, they were focused only on white men. For them, it was a safe bet because fewer than one in six American serial killers is black.

MOUNTING HYSTERIA

But profiles don’t catch killers. Cops do. And in this case, Baton Rouge authorities were making a series of crucial errors, dismissing leads, and looking the wrong way. More than 1,500 white men were swabbed for DNA samples. The task force bought a billboard on the interstate with a sketch of the suspected killer—a white man. Cops announced what kinds of shoes the killer wore at two murder scenes, causing some veteran investigators to worry he would destroy the evidence.

IN 2003, EAST FELICIANA PARISH DEPUTIES REMOVED CONCRETE FROM IN FRONT OF A HOME WHERE DERRICK TODD LEE ONCE STAYED WITH A GIRLFRIEND IN JACKSON, LOUISIANA. THEY UNSUCCESSFULLY SEARCHED FOR THE BODY OF RANDI MEBRUER, 28, OF ZACHARY, WHO DISAPPEARED IN 1998. THE BODY HAS NEVER BEEN FOUND.

Associated Press

Worse, police began to realize they might have more than one serial killer prowling Baton Rouge at the same time, a frightening if statistically unlikely possibility.

Mounting public hysteria was confusing matters even more. More than 27,000 tips flooded in from the public and swamped the task force. Many leads were simply ignored, even when they came from other police agencies. When Dianne Alexander’s composite sketch was shared with Baton Rouge cops, they dismissed it because her

would-be rapist was black and drove a Mitsubishi. Their killer was a white man driving a white pickup. Moreover, Dianne was black—although very fair—and their killer favored white women.

On September 4, a woman called the task force to tell them that she knew the killer, a man named Derrick Todd Lee, her convicted stalker. But when investigators went to Lee’s house and saw he was a slightly pudgy black man and didn’t drive a white work truck, they dismissed him as a suspect.

Enter Detective David McDavid, a small-town cop from Zachary, 15 miles (24 kilometers) north of Baton Rouge. In 1992, he had worked on the disappearance and murder of Connie Warner, a forty-one-year-old mother abducted from her Zachary home with no signs of forced entry. Her badly decomposed body was found in a Baton Rouge ditch more than a week later.

A year later, he caught the case of two necking teenagers who were slashed by a machete-wielding Peeping Tom in a cemetery. The attacker ran away when a cop drove up to roust the kids. One of the victims later identified a local troublemaker well known to Zachary cops: Derrick Todd Lee, a petty burglar, stalker, and peeper with a long rap sheet.

Then in 1998, Detective McDavid pulled another missing-persons case. Twenty-eight-year-old single mom Randi Mebruer had disappeared from her Zachary home. A pool of blood congealed on the floor as her three-year-old son wandered in the front yard, but her body was never found. McDavid quickly noticed that Mebruer lived just around the corner from the house where Connie Warner had disappeared six years before—and in a neighborhood where Derrick Todd Lee was suspected of peeping for the past year or so.