Delivered from Evil: True Stories of Ordinary People Who Faced Monstrous Mass Killers and Survived (26 page)

Authors: Ron Franscell

Tags: #True Crime

AFTER FIRING AT WILL FOR MORE THAN NINETY MINUTES, TEXAS TOWER SNIPER CHARLES WHITMAN WAS KILLED BY TWO AUSTIN COPS ON THE TOWER’S OBSERVATION DECK.

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

He commenced shooting anyone he could see. He had a 360-degree field of fire, and he proved lethal.

For the next ninety-six minutes, Whitman killed with uncanny precision. He hit some victims up to 500 yards (457 meters) away, and zeroed in on frantic, running bodies with deadly accuracy. He dropped them all: first, the pregnant freshman and her boyfriend, who tried to shield her …then the young math professor …Peace Corps volunteer Thomas Ashton, who was simply walking toward the sound of gunshots …the student running away …the cop who peeked out from his hiding place …the Ph.D. candidate with six kids …the new high-school graduate and his girlfriend who dreamed of being a dancer …the city electrical repairman who just wanted to help somebody …the seventeen-year-old girl who attended the same school where Kathy taught …the electrical engineering student who’d take another thirty-five years to die from his wounds …

With one hundred fifty bullets, Whitman hit almost fifty people.

All the while, a CBS television crew was filming inside the free-fire zone, and news photographers were risking their lives to snap images for the next day’s paper. Citizens all over the city—including Whitman himself—had dialed their transistor radios to listen to the live coverage.

Minutes after the first shot, Austin police scrambled to the scene, where one of them had already been killed. A police sniper was sent aloft in an airplane, but Whitman drove them away with his gunfire. As word spread on the radio, dozens of angry citizens arrived with deer rifles and returned fire at the Tower.

As police slowly moved across the killing ground toward the Tower, they helped the wounded as best they could, even as Whitman continued to fire at the ambulances trying to save them.

A handful of policemen finally got to the Tower. Once inside, Officers Ramiro Martinez and Houston McCoy—with the help of a civilian deputized on the scene—crept to the observation deck but found the door wedged shut. When McCoy finally breached the door, they both snuck toward the sound of Whitman’s shots, even as bullets from the ground ricocheted off the walls around them.

McCoy caught Whitman’s eye for a split second, then blasted him in the face with a shotgun. Charlie’s head flipped back and his body spasmed as McCoy hit him with another blast in the left side of his head. At the same moment, Martinez emptied six shots from his service revolver into Whitman.

He was dead, but McCoy and Martinez ran to his twitching body and each fired a last shot at point-blank range into him. As Whitman’s blood drained into a rain gutter near his shattered head, McCoy grabbed a green towel from Whitman’s footlocker and waved it to the people on the ground.

The siege was over. At 1:24 p.m., Charles Whitman was dead.

PUTTING THE PIECES TOGETHER

Whitman was likely already dead when Cap and the others hiding in the jewelry store—and most people on the ground—escaped into an alley and scrambled over a wooden fence into the arms of paramedics on the other side. In the alley, Cap saw ordinary people aiming their rifles toward the Tower, and a few more pieces of this bloody puzzle fell into place.

Several injured people were already in the ambulance, including the driver himself, who was critically wounded. Driver Morris Hohmann was responding to the victims on West Twenty-Third Street when one of Whitman’s bullets pierced his leg artery. His partner used his belt as a tourniquet and took him to Brackenridge Hospital with the other victims.

At Brackenridge, the dead and wounded were piling up in the city’s only full-service emergency room. Chaos reigned in the hospital’s hallways, where cops, reporters, and relatives rushed around among the dead and dying. Meanwhile, hundreds of local citizens lined up at Brackenridge and the local blood center to donate.

In the ER, somebody told Cap what had happened: A madman in the Tower had been shooting innocent people, and many were dead.

When a doctor finally saw Cap, he found serious shrapnel wounds in his upper left arm, the front of his left leg, his back, and his left hand—all caused by Whitman’s soft-tipped bullets splattering against his friend Dave’s wrist bones and the walls and sidewalks of Guadalupe. He had also been hit directly in the soft flesh of his upper right arm; the bullet furrowed 6 inches (15.2 centimeters) across the meat of his triceps. None of the injuries were life-threatening, but all had come close to something much more serious.

Brackenridge soon transferred Cap to the University Health Center, where he spent a week recuperating from his wounds, some of which suppurated for months. There, he was told that Thomas Ashton, his Peace Corps buddy, had been killed. And he began to contemplate how close he had come to death.

Outside of his hospital window the Tower loomed. This edifice, seemingly within an arm’s reach, had come to symbolize so many things to so many people, including Charles Whitman. Now it became a symbol of something else to Cap Ehlke: the nearness of death.

“As I lay in the clean, white bed at the clinic, I could look out the window and see that lofty tower,” he wrote later. “At night it was lit up. Piercing into the dark sky, it gave me an eerie feeling, as stark as death itself. It made me think about the ultimate meaning of things.”

After he was released, Cap joined up with another Peace Corps group that had been sent to Mexico to practice teaching before shipping out to the Middle East. He was assigned to a high school in Mexico City for a few weeks, but he felt out of sync with the group. His wounds weren’t healing properly, and he was still obsessed with his brush with death. Or with God.

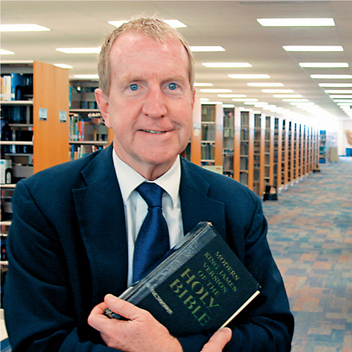

NOW A PROFESSOR OF RELIGION, WRITING, AND LITERATURE AT WISCONSIN’S CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY, CAP EHLKE FINALLY FULFILLED HIS DREAM OF SEEING THE WORLD BEFORE COMING HOME TO MILWAUKEE, WHERE HE GREW UP, TO BECOME A LUTHERAN MINISTER.

Ron Franscell

The shooting had jolted him back into a spiritual focus. He still wanted adventure, but maybe it wasn’t as far as Iran or all the other places he never knew. Maybe it was closer than all that.

He picked up the phone and called the seminary. The new semester had already begun, he was told, but they took him anyway.

The next summer, he went to Iran to visit some of his old Peace Corps friends, including Dave Mattson, whose hand had been reattached by surgeons. He explored Europe that summer, too, before traveling to Jerusalem six weeks after the Six-Day War between Israel and Egypt. The air was electric in those days, and it thrilled him.

Later, he attended the Hebrew University of Israel before finishing at seminary. He was sent to a small church in Little Chute, Wisconsin, and made a family. He was, at last, the minister his father expected him to be.

In time, he returned to Milwaukee as an editor for a Lutheran publishing house, where he worked for fifteen years. Cap eventually collected four master’s degrees and a doctorate, and he took a teaching position at Concordia University, a Lutheran college on the shores of Lake Michigan in Mequon, a northern suburb of Milwaukee.

For many years, he kept the bloodied pants he wore that day in Austin, but they have disappeared. So have some of the memories he thought he’d never forget. Somewhere there’s a box full of clippings and mementos from those dark days, but he has lost track of them. Reading other people’s memories might somehow taint his own.

“I just have never looked at my survival as some kind of great accomplishment,” he says now. “It was just something I was involved in. In some ways, it seemed kind of morbid to want to revisit it.”

He feels no animosity toward Charles Whitman, partly because he never saw it as a personal attack.

“What he did was terrible, and he went over the edge,” Cap says. “It was like being hit by lighting, being touched by some force outside of me. I happen to have been shot by him, but my relationship to Charles Whitman is no different than someone’s who wasn’t even there.

“If anything, it made me aware of how we are always close to death. An inch or two either way can make all the difference.”

WORKMEN USE WIRE BRUSHES TO REMOVE BLOOD STAINS FROM THE CONCRETE SIDEWALK IN FRONT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS TOWER IN AUSTIN, THE DAY AFTER CHARLES WHITMAN’S ASSAULT.

Associated Press

THE ENIGMA IN THE TOWER

In ninety-six horrifying minutes, Charles Whitman had killed fourteen people and wounded thirty-one. The discovery of his wife’s and mother’s corpses brought the day’s grim toll to sixteen.

A long line of American mass murderers preceded Charlie Whitman, and a longer line came after, but the Texas Tower massacre became an archetype for wholesale slaughter possibly because of the iconic Tower itself. Or possibly because it would be twenty-two years before another crazed shooter—James Huberty, at the San Ysidro McDonald’s in 1984—would exceed Whitman’s grisly body count (see

chapter 3

).

In the days after the orgiastic slaughter in Austin, an autopsy showed that Whitman had a malignant, walnut-sized tumor deep in his brain, just as he had feared. But doctors concluded that it was unlikely to have caused his rampage, even though they believed it might have killed him within a year.

Some scoff at the suggestion that a tumor, drug abuse, insomnia, or anything but raw evil caused Whitman’s rampage.

“Charlie Whitman knew precisely and completely what he was doing when he ascended the University of Texas Tower and shot nearly fifty people,” wrote Gary Lavergne, whose meticulously detailed book,

A Sniper in the Tower

, stands as the definitive account of the crime. “He could not have done what he did without controlled, thoughtful, serial decision-making in a correct order to accomplish a goal. Nothing he did remotely appears undisciplined or random … [He] was a cold and calculating murderer. Those who say they can’t believe he would commit such a monstrous crime are only admitting that they didn’t really know him.”

Charlie Whitman died as he had lived, an enigma.

Ironically, he was buried beside his beloved mother—his first victim—in a Catholic cemetery in Florida. A priest blessed Charlie’s gray, flag-draped casket as it was lowered into hallowed ground, saying he had obviously been mentally ill and was therefore not responsible for the sin of murder.

Kathy Leissner Whitman, only twenty-three when her husband stabbed her to death, was buried in Rosenberg, Texas, not far from the little town where she grew up.

As so often has happened after gun crimes, a groundswell of anti-gun hysteria erupted after the Tower massacre. But it was stillborn: Charlie Whitman was a military-trained marksman who possessed legal weapons that he legally purchased. He had no previous criminal record and knew more about firearms than most gun owners do. As many pointed out at the time, he could have taught the gun-ownership courses that any state might have mandated.

For many, it wasn’t what Whitman knew or what he couldn’t control that caused his crimes. He was in complete control of his actions and understood their profound consequences.

“Charles Whitman knew that what he was doing was evil,” Lavergne concluded in

A Sniper in the Tower

. “[He] became a killer because he did not respect or admire himself. He knew that in many ways he was what he despised in others.

“He wanted to die in a big way …he died while engaging in the only activity in which he truly excelled: shooting.”

For two years after the mass murder, the Tower’s observation deck was closed. After it reopened in 1968, a series of suicide leaps forced it to close again in 1974. Finally, after several safety improvements, it reopened in 1999.

Nine years after the killings, when Hollywood proposed a TV movie about the massacre, starring a post-Disney Kurt Russell as Whitman, the University of Texas refused to allow filming at the Tower, saying it would be an affront to the still-raw emotions in Austin.

The Deadly Tower

was eventually filmed at the state capital building in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and aired in late 1975 to lukewarm reviews. The movie itself is five minutes shorter than Whitman’s real-time shooting spree.