Delivered from Evil: True Stories of Ordinary People Who Faced Monstrous Mass Killers and Survived (39 page)

Authors: Ron Franscell

Tags: #True Crime

He briefly attended the University of North Carolina in 1939, then transferred to Purdue, majoring in engineering. But like Arthur Duperrault, he saw war clouds gathering on the horizon in 1940, and rather than wait to be drafted as a grunt, Harvey enlisted in August 1941—four months before Pearl Harbor—as an air cadet in the U.S. Army Air Corps, which was the precursor of the Air Force.

“That’s where the glory is,” he told friends.

While training to fly, war broke out. Twenty-four-year-old Harvey—already an “old” man among the patriotic kids streaming into the service after the bombing of Pearl Harbor—was commissioned as a second lieutenant and assigned to fly B-24 bombers. At first, he flew sub-hunting missions along the eastern seaboard, in which he found no U-boats but played the role of the dashing aviator superbly: He met his second wife, a wealthy seventeen-year-old debutante, at a social function for officers and married her a few months later.

In the fall of 1942, Harvey was sent overseas, where he flew thirty bombing missions from England and Libya. He racked up an impressive file of commendations and an equally impressive number of crashes. But even as his crews and commanders increasingly saw him as accident-prone, his heroic looks and manner always carried him through any turbulence he might have created for himself.

How odd it was, the passersby said later,

that this extraordinarily fit young man

had made no effort to rescue his wife and mother

-in-law who were trapped below him, even

when other Samaritans tried.

While Harvey was bombing Nazis in Europe, his wife bore him a son, Julian Jr. Shortly after being sent back stateside in 1944, Harvey told his young wife that he wanted a divorce. She kept the child and he kept his freedom.

Even before the war had ended, Harvey became a test pilot, adopting a jaunty, unconventional uniform of “a special-cut Eisenhower jacket, pearl-pink chino trousers, and a yellow scarf”—an outfit nobody challenged because he was a war hero and he virtually oozed the gallant aura that endeared him to women and generals alike.

After the war, Harvey became a jet fighter pilot, which only enhanced his legend. Now thirty-one, he met and married another young socialite, twenty-one-year-old Joann Boylen. In 1948, they had a son, Lance, but Harvey knew he was too smart, too handsome, and too damn charming for one woman. He continued his affairs with abandon. And Joann was enraged by them.

ARTHUR AND JEAN DUPERRAULT OF GREEN BAY, WISCONSIN, DREAMED OF A RETIREMENT AT SEA IN THE TROPICS, SO IN OCTOBER 1961, THEY LOADED UP THEIR THREE CHILDREN FOR A “TRIAL RUN.”

Courtesy of Tere Fassbender

ALWAYS A TOMBOY, TERRY JO DUPPERRAULT ADORED HER ADVENTURESOME FATHER ARTHUR, AND SHARED HIS LOVE OF THE WATER.

Courtesy of Tere Fassbender

On a rainy night in April 1949, Harvey, Joann, and her mother were driving on a rain-slicked highway near Valparaiso, Florida. Their car skidded, crashed through a bridge guardrail, and plunged into a dark, deep bayou.

A few minutes after the wreck, passersby found Harvey looking down into the water from the old wooden bridge, unhurt and strangely unemotional. He explained in vivid detail how he had seen the accident unfolding, and, even as the car was tumbling through the air, he opened his driver’s side door and leaped to safety. How odd it was, the passersby said later, that this extraordinarily fit young man had made no effort to rescue his wife and mother-in-law who were trapped below him, even when other Samaritans tried.

A rescue diver and the highway patrolman who investigated the crash were equally suspicious. Harvey’s story just didn’t sound right to them, but they had little hard evidence to prove their belief that Harvey had staged the accident.

Joann’s father demanded a military investigation of the young flier’s story, but there was nothing to be done. Nobody looked further into the curious case, and no charges were ever filed. But a base doctor—not a psychiatrist—took a personal curiosity in Julian Harvey, and after a few informal visits, he concluded that the outwardly glib, charming, and suave Harvey was, in fact, a sociopath who was incapable of love, addicted to danger, a promiscuous liar, and a grandiose narcissist. His assessment was never a part of Harvey’s file.

So Julian Harvey collected his wife’s life insurance payout, and within a few weeks, he was living with another woman.

He collected women at an equally astonishing rate. In 1950, he married his fourth wife, a Texas businesswoman whom he divorced three years later. And in 1954, he married his fifth wife, a bright young woman he met in Washington, where he was again billeted as an Air Force staff officer.

Still fascinated with sailing, Harvey bought a 68-foot (21 meter) yacht called the

Torbatross

. One day, he set sail with friends on the Chesapeake Bay and rammed into the submerged wreckage of the famed battleship

Texas

, a Spanish War hulk that had been bombed by air ace Billy Mitchell in 1921 to flaunt American air power. Harvey and his crew escaped safely, but the

Torbatross

went down, and Harvey collected a $14,258 claim against the U.S. government. One of his passengers, however, found it strange that Harvey had deliberately circled the dangerous

Texas

wreck twice before ramming it directly.

Harvey’s Air Force career continued, apparently impervious to his behavior. He flew 114 combat missions in Korea, and over the course of nineteen heroic years, earned the Distinguished Flying Cross with cluster, an Air Medal with eight oak leaf clusters, and fifteen more decorations.

But he’d also crashed three airplanes and built a reputation for having an unusual number of in-flight mishaps. His renowned unluckiness was credited with an inordinate number of dead-stick landings, midair flameouts, and engine trouble—some of which got him out of dangerous dogfights and flak-filled bombing runs. But never did anyone suspect that the dashing, dauntless Harvey could possibly be shirking his duty. He was just unlucky, that’s all.

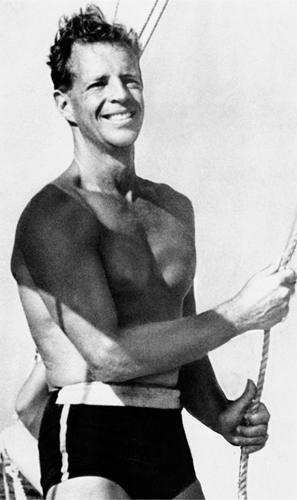

CAPTAIN JULIAN HARVEY, THE DASHING SKIPPER OF THE CHARTERED KETCH BLUEBELLE, WAS A WAR HERO AND FORMER MODEL WHOSE CHARM HAD GOTTEN HIM OUT OF MANY TIGHT SQUEEZES.

Courtesy of Associated Press

Major Julian Harvey retired in 1958 with a medical discharge, but because he had served briefly as a temporary lieutenant colonel, he kept the superior title.

Around that same time, his fifth wife filed for divorce, claiming Harvey’s infidelities and secret anger were intolerable. Escaping the messy business of another split, he sailed his new 80-foot (24 meter) luxury yawl, the

Valiant

, to Havana—but 10 miles (16 kilometers) off the Cuban coast, the

Valiant

caught fire and sank. Harvey and a crewman both escaped unhurt, but again, he collected a $40,000 insurance settlement.

“Julian told the Coast Guard a beautiful story,” one of Harvey’s sailing friends said years later. “He was a real expert at storytelling because he had had so much experience talking himself out of trouble. He told me he set the fire himself because he was in a financial jam and needed the insurance money.”

For the next few years, Harvey drifted through South Florida’s sometimes shady sailing underworld, where gun running, drug smuggling, and insurance scams were common. When investigators went calling, Harvey’s name often came up. Increasingly, his good looks and charisma were no longer enough to float him above suspicion.

In 1960, in Miami, he spied a shapely woman sunning herself on the beach and boldly introduced himself. She was Mary Dene Jordan Smith, an attractive blond TWA stewardess and aspiring writer. Harvey led her to think he was rich, but he was, in fact, flat broke. They married in late July 1961, but their relationship was stormy from the beginning, and their arguments were usually about money. One such fight erupted after Dene had promised to send $25 a month to her ailing father back home in Wisconsin, just to help him pay his medical bills, but Harvey refused to let her.

That fall, Harold Pegg hired Harvey and Dene to crew his ketch, the

Bluebelle

, where they could live and earn $300 a month by taking on Pegg’s paying customers. The first charter would be the Duperraults, a nice little Wisconsin family who paid $515 to sail for an idyllic week in the Bahamas.

But they had enough money that on September 8, Harvey was able to take out a $20,000 double-indemnity life insurance policy on his sixth wife, Mary Dene.

After all, a man with his prodigious record of accidents couldn’t be too careful.

LITTLE GIRL ALONE

Terry Jo Duperrault was in heaven.

For five days, the

Bluebelle

traversed endless, open tropical seas. Her father traded off with Harvey at the helm while the children played on deck. Rene played with her dolls and Brian fished while their mother read books and absorbed the pure sunlight.

They could swim in the mesmerizingly clear blue water around the boat or row the dinghy ashore to explore beaches and jungles. They swam, snorkeled, and fished for lobster. Every night, they anchored off serene island beaches from Great Isaac Cay to Gorda Cay, away from people and light and the cares they left behind.

Terry Jo, an eleven-year-old girl who’d never known a dark day in her life, couldn’t believe life could be so carefree. The turquoise water, the striped fish, the lonely beaches piled with perfect conch shells, the azure sky, and the billowing clouds—she absorbed it all and never wanted to give it back. She even wrote a letter home to her school classmates that said she never wanted to come back.

She was becoming a young woman, too. Her breasts were just beginning to develop, and she felt awkward in her new swimsuit, especially around the handsome Harvey, who seemed to watch her more than the rest. They’d spoken very little, except when they met, and she thought he was nice enough, although his odd eye bothered her.

Her mother, who dabbled in art, fell in love with the colors of the islands, and she imagined coming back. So did Arthur, who told a Bahamian bureaucrat that he intended to build a winter home on Great Abaco Island someday.

On Sunday, they spent their last day at Sandy Point. Arthur met a seventeen- year-old fisherman named Jimmy Wells on the beach and invited him to dinner aboard the

Bluebelle

, where Dene had prepared chicken cacciatore and salad in the galley. The meal was pleasant enough, and everyone was happy.

Afterward, Jimmy left the boat, and as the sun set, Harvey headed for open water, toward home 200 miles (322 kilometers) away. Arthur and Harvey planned to anchor for a few hours in the lee of Great Stirrup Cay, get three or four hours of sleep, then push on to Great Isaac, where they’d again anchor in the lee for a little more sleep, then reach Fort Lauderdale Tuesday night or Wednesday morning.

The Duperraults and the Harveys sat in the

Bluebelle

’s cockpit past dark, reliving the adventure and enjoying the night air. Around 9 p.m., Terry Jo, always the first to bed, went to her main cabin bunk beside the stairs from the deck above, while everyone else stayed up talking. She fell asleep in her clothes, an embroidered white cotton blouse and pink corduroy pedal pushers.