Delivered from Evil: True Stories of Ordinary People Who Faced Monstrous Mass Killers and Survived (35 page)

Authors: Ron Franscell

Tags: #True Crime

Indeed, Michael told several people, including prayer-circle leader Ben Strong, “something big” was going to happen in the school lobby soon. But ever since he’d logged on to a website called “101 Ways to Annoy People” and began a deliberate campaign to nettle his classmates, his grandiose threats rang hollow. He even warned some to stay away from the prayer circle after Thanksgiving, but

most thought it was going to be another stink bomb. He mused in the cafeteria about taking over the school in an armed assault, and kids laughed. When he pulled a handgun on students in the band room the day before Thanksgiving, the kids chalked it up as just another of his infantile pranks. Nobody tattled because nobody took Michael Carneal seriously.

That first Monday after Thanksgiving, he stowed his secret, duct-taped bundle and his olive-drab backpack in the trunk of his sister’s Mazda before she drove him to school. He told her they were props for a skit he was performing in English class that day.

But they weren’t. Michael Carneal’s awkward kit contained two antique shotguns and two .22 rifles wrapped in an old blanket, all stolen from a neighbor’s gun cabinet. In his backpack were a .22 Ruger semiautomatic pistol he also filched from a neighbor’s garage, earplugs, three spare eleven-bullet clips, and more than a thousand rounds of stolen ammunition.

When he arrived at school with his considerable arsenal, Michael entered through a back door into the band room (where a band teacher asked what he was carrying and was satisfied by the same English-skit response), wandered up through the empty auditorium, through back hallways, past the main office, and into the crowded lobby, where the prayer circle was gathering. He walked past his goth friends and put the blanketed bundle on the floor beneath the school’s trophy case.

Somebody asked him what he was carrying and again, he said it was for a class play. Satisfied, the other student turned away, and nobody else talked to him. Michael was again alone in a roomful of people as he pulled out his gun.

Nobody noticed. It angered him that, yet again, nobody noticed.

You’ve got to do this for yourself

, said the voice in his head.

For yourself

.

He slung his backpack off his shoulder and set it on the floor. He unzipped it and reached in. He fumbled with his earplugs and dropped one.

Stupid kid

, he thought to himself.

Can’t even get the earplugs right

.

He racked a clip into his chrome pistol just as Ben Strong said his final “Amen.”

“PLEASE KILL ME”

When the prayers finished, Missy Jenkins felt better. She hugged her friend Kelly and headed toward her book bag. She had only taken a few steps when she heard a

pop

that sounded like a firecracker.

She pivoted toward the sound, her ears ringing. She saw Nicole Hadley fall limply to the tile floor with what appeared to be blood on her head.

She’s faking this

, Missy thought.

This is some kind of a joke

.

The two more random pops rang out, then a rapid-fire series of seven more. The only gunshots she’d ever heard were on TV, and these pops sounded nothing

like that. She was wondering who might pull such a frightening prank when her body suddenly went numb and she crumpled to the floor. To her, it felt as if she floated down. She never felt herself hit the floor, never felt any pain. She lay on the cold floor, unable to move, wondering what was happening.

Screaming students were running all around her. Mandy was crouched over her, making sure she was alive and covering Missy’s body with her own.

“What’s going on?” Missy asked her sister.

“There’s a gun,” she said. Her voice was panicky, her eyes wide.

“A gun? Who’s got a gun?”

“Michael.”

“Michael? Michael who?”

“Michael Carneal.”

It didn’t make sense to Missy. Nothing made sense. She didn’t know what was happening, didn’t know why she couldn’t feel her belly. She knew she must have been shot, but there was no telltale blood on her to mark a wound.

For twelve seconds, Michael fired in steady succession, until his clip had only one bullet left. He never reached for extra bullets, even though he had hundreds at his feet.

Kelly Hard had been hit in the shoulder. Nearby, Kayce Steger lay face-down and not moving. Jessica James, a senior in the band with Missy, had been shot beneath the shoulder and was wracked with violent convulsions as her life bled away.

Principal Bill Bond rushed out into the chaos and took cover with Ben Strong behind a pillar near the shooter. But before they could jump him, Michael dropped his gun and slumped in tears. Bond and Strong rushed in.

“What are you shooting people for?” Strong yelled at the whimpering little boy who had just shot into a crowd of forty teenagers.

“Shooting people,” Michael heard himself say.

“What for?” Ben asked, coming closer.

Michael was in shock. “I don’t know.”

Principal Bond grabbed the gun and trundled Michael into a nearby office.

“Kill me,” Michael cried as he was hustled away. “Please kill me.”

Missy’s algebra teacher, Diane Beckman, knelt by her side, trying to keep her awake. All she could do was pray.

“Am I going to die?” Missy asked her.

“No, you’re not going to die,” she said. “You’re going to be fine.”

“But I’m paralyzed. I can’t feel anything.”

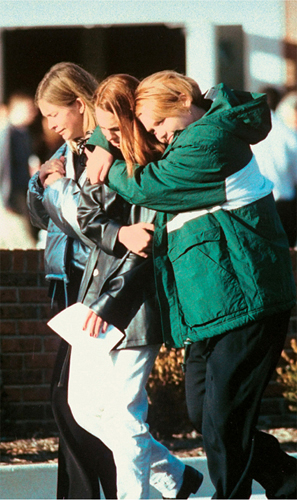

THE GRIEVING BEGAN IMMEDIATELY AFTER FRESHMAN MICHAEL CARNEAL KILLED THREE GIRLS—NICOLE HADLEY, JESSICA JAMES, AND KACEY STEGER—AND WOUNDED FIVE OTHERS DURING HIS SHOOTING SPREE AT HEATH HIGH SCHOOL’S MORNING PRAYER MEETING IN WEST PADUCAH, KENTUCKY, IN 1997.

Getty Images

“No, you’re not paralyzed. You’re just in shock,” she insisted. “You’re not paralyzed.”

“But I know I am because I can’t feel my legs or my stomach,” Missy said. Suddenly, Missy felt like vomiting, and Beckman helped her turn to one side to throw up without choking herself.

Before the ambulances arrived, Missy lapsed into a dream: She was walking and laughing with a stranger when a bicyclist aimed right at her. She jumped out of harm’s way, then resumed her walk. Then she was awake again, staring at the ceiling of Heath High School. That’s all she remembered about the dream, but while she had feared dying before, she was inexplicably at peace now.

Paramedics, delayed by morning rush hour in the city and the two-lane back roads, finally arrived and quickly focused on the three girls most seriously injured—Nicole Hadley, Kayce Steger, and Jessica James. In a few moments, they gingerly slid Missy onto a backboard and wheeled her to a waiting ambulance for the 12-mile (19-kilometer) journey toward the hospital and the rest of her life.

Michael Carneal, an awkward misfit who only wanted to be liked, had fired ten bullets into a crowd of fellow students, none more than 50 feet (15 meters) from him. Three were dead or dying, and five were wounded.

And in less time that it takes to say “Amen,” Missy Jenkins’s life was changed forever.

WAKING UP FROM A NIGHTMARE

As Missy was wheeled into the emergency room, many of the doctors and nurses were weeping. They, too, had children at Heath High School, and they didn’t know who would be wheeled next through the ER doors.

Doctors began to work on Missy, hooking her up to a chest tube and IVs. They asked her to move her legs, and although it felt to her like she was, she wasn’t. Using a needle, they prodded her body to find out where she could feel and where she couldn’t.

They also found the entrance wound, a small hole in her upper left chest, just below her collarbone, but they would need X-rays to know more.

Missy’s distraught family began to arrive at the hospital, and the doctor allowed them to visit her for just a few minutes before she went to radiology. She read the sadness and fear in their faces. Some cried.

Ironically, Missy comforted

them

. She had tried to make herself cry but couldn’t. She was at a strange peace with what had happened to her less than an hour before. She told them they shouldn’t cry because she was alive.

The X-rays revealed a more sobering truth. A single bullet had entered Missy’s chest, punctured her left lung, and crashed into the T4 vertebra, splattering shards of lead and bone into her spinal cord before it exited just between

her shoulder blades. While the spinal cord itself was not hit by the bullet, the fragments had paralyzed Missy below the chest and doctors believed that trying to remove them would only do more damage.

She had a long rehabilitative road ahead, they said, but she would probably never walk again.

Missy didn’t understand all the medical talk, but she heard what she needed to hear. She couldn’t fathom being confined to a wheelchair for the rest of her life, which had hardly begun. She wondered whether the paralysis might go away sometime.

She also learned that Mandy had narrowly missed serious wounding—or worse. At the hospital, somebody noticed an angry red scrape across Mandy’s neck where a bullet had grazed her. Suddenly, the twin sisters realized that they had both escaped death in miracles measured by millimeters.

That night, before her family left the hospital at the end of a horrifying day, Missy asked to speak privately with her mother.

Missy told her that she had forgiven Michael Carneal, who had paralyzed her for life just hours before.

It stunned her mother, but she understood the strength of Missy’s faith, if not her willingness to forgive her would-be killer so quickly. Later, Missy’s mother shared her decision with the rest of the family who, in their own time, came to agree with her.

“It was like I was in a dream … and I woke up,” Michael Carneal told a teacher while he sat in the principal’s conference room waiting for police to arrive.

“I looked at him and he just had this glazed look in his eyes,” Principal Bond said later. “When I got the gun, I told him to go to the office and sit down. He didn’t react any more than if I had caught him smoking in the boys’ room.”

When asked by investigators why he shot

his fellow classmates, Michael’s first

response was that he was tired of being

teased and bullied, but he admitted that none

of his vaguely described tormenters was in

the lobby that day.

Less than two hours after the rampage, Michael was sitting in the police station. When asked by investigators why he shot his fellow classmates, Michael’s first response was that he was tired of being teased and bullied, but he admitted that none of his vaguely described tormenters was in the lobby that day.

“Was you mad at somebody?” McCracken County Sheriff’s Detective Carl Baker asked him.

“Not anybody in particular.”

“Wasn’t mad at your mom and dad?”

Michael shook his head. “Uh-uh.”

“Mad at the teachers?”

“Not really.”

“You mad at the principal?”

“Uh-uh,” Michael said. “I guess I just got mad ’cause everybody kept making fun of me.”

The kids at school called him “freak” and “nerd” and “crack baby,” he said as he began to cry.

He described in some detail how he had broken into a neighbor’s garage on Thanksgiving to steal guns and ammo from a locked cabinet. He had stashed them in an Army duffel bag one night and carried them home, where he crawled through his bedroom window and hid them in his closet. Shortly before the shooting, he said, he took some of the guns to a friend’s house for safekeeping. The rest he wrapped in a blanket, secured them with duct tape, and shoved them under his bed.

When police searched his room, they found more than two dozen empty cartridge boxes, a typewritten note titled “The Secret” on his nightstand, the handwritten lyrics to a song called “Paralyzed Monkey,” and “Mist-Erie,” a short story Michael had written about atomic bomb testing.

Detective Baker walked Michael through the actual shooting—or what little he remembered.

“I was just sitting there and I reached in my backpack and pulled out a handgun,” Michael recounted calmly.

“What kind of handgun was it?” Baker asked.

Michael would describe himself as being in

a transfixed hypnotic state while he was

firing the pistol, shooting more at movement

and shadows than at specific people.

“It was a .22 Ruger, and I put in a clip and turned off the safety and cocked it and then just started firing.”

“Who all was standing in that group, do you know?”

“Uh-uh.”

“Did you know any of the kids in that group?”

“I knew Ben.”

Oddly, Michael didn’t mention his dear friend Nicole Hadley, whom he had shot in the forehead and who was, at that very moment, on life support.

Or Kayce Steger, the girl he had asked on a date and who was already dead. Or Missy Jenkins, his friend from marching band, now paralyzed. Or any of the other students whom he had lived and gone to school with all his life in his small town.