Delivered from Evil: True Stories of Ordinary People Who Faced Monstrous Mass Killers and Survived (38 page)

Authors: Ron Franscell

Tags: #True Crime

Steeped in Missy’s abiding faith, it is a remarkable summary of survival, not sorrow.

“I will never forget what Michael did to me. How can I?” she writes in her book. “I’m reminded of it every day when I can’t jump out of bed in the morning, reach the cabinets in our kitchen, or stand face to face with my husband. There will never be closure.

“But … I forgave him and my future was enlarged. It helped me discover a Missy Jenkins I never knew existed.”

THE WIND WAS IN THE SOUTHEAST,

although in the blackness of the night sea, it mattered little. Storm clouds hid the pale crescent moon and stars. A child, alone and adrift, couldn’t see her hand in front of her sunburned face. Now it was beginning to rain.

But as the drops hit the black water, it glowed.

She didn’t know the sea. She didn’t know about the tiny creatures that emit sudden, ephemeral flashes of light when disturbed by a swimmer’s hand, a boat’s oar, a zephyr, the slicing prow of a ship, or a drop of rain. She didn’t know their magical light had evolved over eons as a warning against danger and death from predators.

She only knew the surface of the sea all around her flimsy cork raft was suddenly luminous, as if the stars had disintegrated into blue-green dust and fallen into the opaque sea, like she, too, had fallen into the sea. It had happened so fast—the waking, the blood, the rising water, the gun, the sudden silence after the boat disappeared with a sigh beneath the swirling waves, taking her mother and brother with it.

It all felt like a dream.

Arthur Duperrault dreamed big.

He’d grown up in Green Bay, Wisconsin, a little port and paper city on the shores of Lake Michigan that epitomized Midwestern wholesomeness. And

Arthur epitomized Green Bay: Studious, sober, and decent, he was president of Green Bay West High School’s Class of 1939 and a champion debater.

After graduation, he enrolled at Lawrence College in Appleton, Wisconsin. But during his freshman year in 1940, when the Nazi blitzkrieg in Europe and Japanese aggressions in the Pacific threatened to draw America into war, the muscular, red-haired Arthur dropped out of college and enlisted in the Navy.

The Navy trained him as a medical corpsman and sent him to the Burma Road, a rugged mountain route used by Britain to supply the Chinese in their war against Japan. But it was on the transport to the Far East that Arthur fell in love with warm, tropical seas.

In almost two years with Allied troops in the jungles of Burma, Arthur won the admiration of his officers as he tended to men with jungle fevers and battle wounds, often in the harshest conditions. After the United States entered the war, the Navy shipped Arthur home to Washington, D.C., but it was too far from the action to suit the adventurous Midwesterner, so he volunteered to go back to China as a medic for another year.

In 1943, at the height of the war, he was assigned to the Pentagon. In Washington, he met the spirited, dark-haired Jean Brosh, a small-town Nebraska girl who worked as a secretary at the FBI headquarters. They married in late 1944, and when Arthur was honorably discharged in November 1945, they returned to Wisconsin to start a family and a new life.

For Arthur, that meant returning to college. He enrolled in Chicago’s Northern Illinois College of Optometry on the GI Bill, boarding at the school during the week and returning home on weekends for four years. For Jean, it meant raising their young son Brian and being patient.

As Arthur opened his optometry practice in Green Bay, Jean gave birth to a daughter, Terry Jo. As Arther’s practice grew, so did his family. Another daughter, Rene, was born in 1954. The Duperraults were living the idyllic postwar life, with all the professional honors, personal achievements, and profits that came with it.

Brian, the eldest, was his father’s shadow. He went everywhere Arthur went and did everything his father did. Like his father, he grew up short but athletic.

The middle daughter, Terry Jo, was a tomboy who preferred the rough and tumble life. She grew up tall and pretty, and by the time she was ten, she was already taller than her older brother. She often played alone in the woods, inventing her own adventures, scarring her knees, and, at least once, suffering a gash that her mother—always the farm girl—stitched up herself. Terry Jo even hated summer camp because the other girls were such … girls. She was always happy to accompany her beloved father to the lake, where he taught her to fish and swim. He was her one and only hero.

Rene, the youngest, was the dainty one. Petite and blonde, she refused to wear “boy clothes” like her sister and preferred dolls and tea parties to roughhousing.

“Doc” Duperrault, as he became known, was as innovative and adventurous in his practice as in his life. He became a respected leader among his peers, largely through his early embrace of contact lenses, decades before they became popular.

But Arthur was never satisfied with sitting back or procrastinating. He stayed unusually fit and involved. He became a state handball champion, a tireless volunteer at the local YMCA, and a passionate golfer. He also won national attention when he dug frantically in a collapsed trench for hours to rescue the family dog and in another heroic act, leaped fully clothed into the frigid water of Green Bay to rescue a child who was drowning.

MAIDEN VOYAGE

Arthur also became a skilled sailor, and he dreamed of a great shipboard adventure with his family in the tropics. Family weekends in Wisconsin were often spent on the water, but Arthur fantasized about living a year at sea, sailing port to port, educating their three children—Brian, now fourteen; Terry Jo, eleven; and Rene, seven—under sail in both academics and life, following the wind on a once-in-a-lifetime odyssey.

Nearing forty in 1960, he feared the ideal moment might soon pass. But even if his passion for a life at sea was doubtless, Arthur wasn’t certain whether his family shared his dream. So he planned a kind of “shakedown” cruise—one season at sea, maybe a year if it worked out. He hired an optometrist to run his practice, and in the fall of 1961, Arthur and Jean took their children out of school and headed to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where a 60-foot (18.3 meter) chartered ketch named the

Bluebelle

waited for them.

The

Bluebelle

, a sleek, two-masted sailboat, was a former racing yacht, and its lines recalled an elegant past. A 60-foot (18.3 meter) tall mainmast and 45-foot (13.7 meter) tall mizzen mast towered over the graceful, snow-white hull. The boat’s white wooden dinghy and black rubber life raft were stowed to the port side of the cabin; an oval cork life float—essentially a white, canvas-covered life ring with rope netting—was lashed starboard.

With a 13-foot (3.9 meter) main cabin that contained two sleeping areas, a kitchenette, and a head, plus an aft sleeping berth, the

Bluebelle

would be perfect for the five Duperraults and their hired skipper.

In early November, Arthur chartered the

Bluebelle

for the Duperraults’ first cruise, a week’s journey to the Bahamas and back. It was to be the first test of the family’s seaworthiness, the first hint of whether life on the water for long periods would be smooth sailing—or a shipwreck. Either way, Arthur would know quickly within a few days at sea.

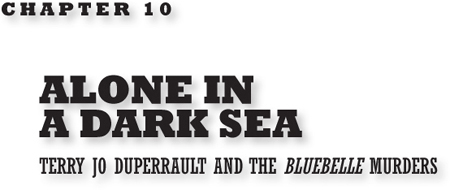

JOHN GALANAKIS, A SEAMAN ABOARD THE GREEK FREIGHTER CAPTAIN THEO, SNAPPED THIS PHOTO OF 11-YEAR-OLD TERRY JO DUPERRAULT ON HER LONELY CORK RAFT JUST MOMENTS BEFORE HIS SHIPMATES PLUCKED HER FROM THE SEA.

John Galanakis

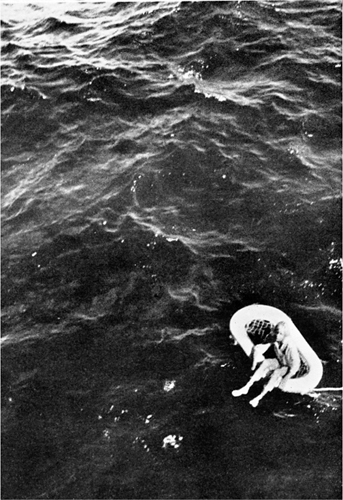

THE DUPERRAULT CHILDREN, FROM LEFT, BRIAN, RENE, AND TERRY JO, KEPT UP WITH THEIR SCHOOL LESSONS BY STUDYING UNDER THEIR MOTHER’S WATCHFUL EYE AT A FLORIDA CAMPGROUND WHILE THEIR FATHER SHOPPED FOR BOATS AND ARRANGED THEIR MAIDEN VOYAGE ABOARD THE

BLUEBELLE

.

Courtesy of Tere Fassbender

On November 8, 1961, the

Bluebelle

was ready to sail. Early that balmy Wednesday morning, the Duperraults arrived at Bahia Mar Marina in Fort Lauderdale with food, clothing, and all the provisions they would need for the week. The children played on deck while everything was made ready.

The

Bluebelle

’s owner, a swimming-pool contractor named Harold Pegg, met them at the slip with a load of ice and introduced them to their captain and his “crew,” who happened to be the skipper’s wife.

The captain was a strapping man, muscular, tanned, and movie-star handsome. His wavy hair gave him a hero’s air. He didn’t make small talk, and when he spoke, he spoke in a dignified, proper way—except for a slight stammer and a bit of a lazy eye. His blonde wife, who was very pretty, slender, and more expressive, would be his first mate and cook. She said her name was Dene, and she, too, was originally from Wisconsin, a former airline stewardess who had married the captain only three months before. This voyage was to be a kind of honeymoon for them, too.

So the time had come for Arthur Duperrault and his family. While Brian helped throw off the lines that tethered them to land, the skipper powered up the

Bluebelle

’s 115-horsepower Chrysler engine, and they motored toward open water. Soon, they were under sail into an 18-knot southeasterly wind, slicing through the warm waves toward their first stop: Bimini.

If Arthur had any lingering doubts about his children’s sea legs, they were dashed as he watched Terry Jo and Brian scramble out on the bowsprit like old shellbacks to feel the sea-spray in the face and to watch the razor-sharp bow carve through the chop. They were laughing and happy. It’s how he had always pictured it. His fantasy mariner’s life was under way.

But in his dreams, Arthur had never imagined someone else at the helm. And this captain, a man named Julian Harvey, was plotting a nightmare course.

CHARMING DEVIL

By all outward appearances, Julian Harvey led a charmed life.

Born in New York City in 1917, he was five when his parents divorced. While his mother became a chorus girl at Shubert’s Winter Garden, a Midtown Manhattan theater where some of the biggest names on Broadway played, Julian and his younger sister were raised by a wealthy aunt and uncle on Long Island.

Young Julian—he hated his name because he thought it was unmanly—grew up extraordinarily handsome, funny, and bright. He dressed impeccably, was outgoing, and became a graceful gymnast. Athletic and popular with the girls, he led a privileged childhood, even as a teenager during the Depression.

In high school, he fell in love with boats. He built several boats of his own and sailed them in Long Island Sound.

He also fell in love with women, with more complicated results. A brief high school marriage had been made necessary by such romantic abandon—the first of many in Julian Harvey’s future.

After graduation in 1937, Harvey worked for a time as a door-to-door salesman, but cold-calling often set off a nervous stammer and caused his lazy eye to roll uncontrollably, so he quit. For about a year, he modeled for New York’s prestigious John Robert Powers Agency, where his portfolio noted his “magnificent build.”