Delivered from Evil: True Stories of Ordinary People Who Faced Monstrous Mass Killers and Survived (4 page)

Authors: Ron Franscell

Tags: #True Crime

HOWARD UNRUH WAS CAPTURED BY CAMDEN POLICE ONLY MINUTES AFTER HIS “WALK OF DEATH.” WHEN ONE ARRESTING COP ASKED HIM IF HE WAS “PSYCHO,” UNURH REPLIED, “I’M NO PSYCHO. I HAVE A GOOD MIND.”

Associated Press

The torn white curtains at the shattered window rustled and the long-limbed Unruh appeared to the police below.

“Okay,” he shouted. “I give up. I’m coming down.”

“Where’s that gun?” the cop hollered.

“It’s on my desk, up here in the room,” Unruh told him. “I’m coming down.”

Within seconds, a coughing Unruh appeared at the back door, his hands held high. While cops patted him down and cuffed him, angry onlookers cried out. “Lynch him!” they said. “Hang him now!”

But Unruh remained impassive. He surrendered as serenely as he had killed.

“What’s the matter with you?” one of the angry cops asked him. “You a psycho?”

Unruh looked at the cop, his burned, dark eyes empty.

“I’m no psycho,” he said. “I have a good mind.”

Amid the chaos of the siege, a little boy’s voice sounded out.

“Help us!” he cried from a second-floor window in the building next to Unruh’s apartment. “He’s killing everybody!”

Even as cops prepared to smoke out the killer barely twenty feet away, the child crawled out onto a first-floor roof.

It was Charles Cohen.

He’d emerged from his closet to find his mother’s bloody body on the floor, and his father’s corpse lay in the street just below him. A cop rushed up to the Cohens’ living quarters to pull Charles to safety, as Unruh hid in the apartment next door.

The cop scooped Charles up and took him to a waiting police car.

“You watch,” he said. “I’m going to be a hero, kid.”

From that moment, Charles Cohen never spoke about the tragedy on Cramer Hill again that morning. He wanted to forget. He wanted the world to forget.

But there came two moments when he could remain silent no longer.

The first time was when he told his new bride, on their wedding night, the dark secret he carried.

And the next time was when the world—which hadn’t forgotten, but hadn’t exactly remembered, either—appeared ready to forgive Howard Unruh.

COMING UNDONE

Even before all the bodies had been counted and collected, Howard Barton Unruh sat expressionless in a Camden detective’s office.

Less than ninety minutes before, he was murdering his neighbors in a brief but methodical “walk of death,” as the newspapers and radio broadcasts would soon call it. Now, here sat a tall, lean, detached young man in a white shirt and bow tie, his hands in his lap as if he were in church. He was cooperative and polite to the officers, even thanked them for doing their job. His pale face betrayed neither worry nor remorse. Behind his wire-rimmed glasses, he looked almost too fragile to be a mass murderer.

But he was a murderer, and he confessed it readily.

“I deserve everything I get,” he told them, “so I will tell you everything I did and tell you the truth.”

For more than two hours, detectives pieced together the puzzle of Howard Unruh, a man who’d never gotten a jaywalking ticket, much less shown homicidal tendencies.

Under questioning by District Attorney Mitchell Cohen (no relation to the druggist), Unruh described in scrupulous detail how he hated his neighbors, how they’d plotted against him, and how he’d been planning to kill them all for more than two years. He meticulously recounted how he gathered his ammunition, laid out his gun, left a note to be awakened at 8 o’clock sharp, ate his cereal and eggs, and then killed as many people as he could.

He unemotionally described the murders, one after the other. He narrated each death as if it were no more hideous than finding a dead sparrow on the sidewalk. He’d spilled more blood than any single killer in living memory, but to hear him tell the story, it was no more dramatic than a morning walk in the park.

None of it made any sense.

Howard Barton Unruh was born January 20, 1921, in Haddonfield, a Camden suburb. A younger brother was born four years later.

But their parents separated when Howard was ten. The boys went with their mother to Camden, where she worked for a soap factory, while their father lived and worked on a dredge in the Delaware River.

Howard grew up solitary, preferring always to be alone. He played with his train sets, read voraciously, and collected stamps. He never brought friends home, and he seldom made trouble.

Unruh’s pale face betrayed neither worry

nor remorse. Behind his wire-rimmed

glasses, he looked almost too fragile

to be a mass murderer.

In school, Unruh appeared to be studious, but he was an average student. He never had a girlfriend, never went to a dance, and avoided most social activities. Except church. He took to carrying a Bible with him everywhere, faithfully attending Sunday services and Monday Bible classes at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church.

After graduating from Woodrow Wilson High School in 1939, he worked as a pressroom helper at a publishing company, then briefly as a sheet-metal worker at the Philadelphia Navy Yard until he enlisted in the Army in 1942.

Unruh was stationed stateside until his self-propelled field artillery unit landed in Naples, Italy, in 1944. He served as a tank gunner in battles across Italy, France, Belgium, Austria, and Germany, winning two battle stars and sharpshooter ribbons, and taking meticulous notes about the Germans he killed along the way.

Every day, he wrote to his mother. Sometimes, his letters posed deep theological questions that troubled him; other times, they discussed military matters as if his mother had technical expertise.

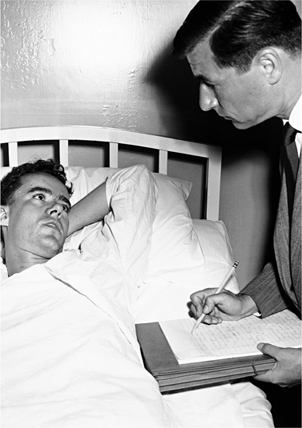

CAMDEN COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY MITCHELL COHEN, RIGHT, INTERROGATED CONFESSED GUNMAN HOWARD UNRUH FOR TWO HOURS AFTER THE SHOOTING UNTIL HE REALIZED UNRUH HAD BEEN SLIGHTLY WOUNDED IN THE BUTTOCKS. AFTER UNRUH WAS TREATED AT A LOCAL HOSPITAL, COHEN CONTINUED HIS QUESTIONING AT UNRUH’S BEDSIDE.

Associated Press

In November 1945, he was honorably discharged and came home to his mother’s flat in Camden. His family noticed a distinct difference in him, as if he had retreated into a shell. He rarely spoke about the war. He threw out his stamp collection and started to collect guns. He built a target range in his basement, stacking newspapers against the far wall to absorb the bullets he often reloaded himself. Neighbors often heard the

pop-pop-pop

of his cellar gunfire, but they thought young Unruh must have been hammering on a carpentry project.

His church fixed him up with a young woman and subtly encouraged them to marry. But after a while, Unruh broke it off, promising the girl it would be “a mistake” to marry him.

One day in 1947, Unruh spotted a German Luger in a shop window. When he inquired, the clerk told him he needed a permit from the Camden police before he could buy it. Dutifully, he got the permit a few days later and paid $37.50 for the gun—the same gun he used to kill his neighbors two years later.

Unruh took a few odd jobs after the war, but he never worked for very long. Hoping to study pharmacy at Temple University, Unruh used the GI Bill to pay for some college prep classes and even enrolled at Temple, where his nemesis and later victim Maurice Cohen had graduated, but he quit after three months. He sold some of his train sets for pocket money and never worked again.

Nothing about Howard Unruh’s first twenty-eight years screamed bloody murder. Sure, he was a little eccentric. Maybe a loner. Maybe a loony. But a cold-blooded killer? What made Howard Unruh come undone?

JUSTIFYING MURDER

While Unruh was being interrogated, detectives scoured his mother’s apartment for clues to his state of mind. They found more than they could have imagined.

They found his basement shooting gallery and bullet-making equipment easily enough. They also found his cache of war souvenirs, from bayonets and pistols to ashtrays made from artillery shells. They found the machete he planned to use to cut off the Cohens’ heads.

There were many books—some about gun collecting, others about sexual science.

In his bedroom, detectives discovered the notebook containing sketchy details of his dalliances.

Some of the men were listed only by first names, some simply as “a man.” Some names were followed by the words “a car.” Beside each name was a date, and sometimes there were several names on the same date. He’d make such notations every night for weeks at a time.

And beside Unruh’s bed, they found his Bible, lying open to chapter twenty-four of St. Matthew, the chapter in which Christ predicts the destruction of the temple and all the catastrophes to come. “The lord of that servant shall come in a day when he looketh not for him, and in an hour that he is not aware of,” it said. “And shall cut him asunder, and appoint him his portion with the hypocrites: there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

The interrogation of Howard Unruh might have continued longer if DA Cohen hadn’t seen blood puddling under Unruh’s chair. When they examined him, they found he’d been shot in the buttocks with a small-caliber bullet. He was rushed to the hospital, the same hospital where his victims had been taken, but doctors determined that removing the small bullet would do more damage than the bullet itself had done. For the rest of his life, he carried the slug in his butt.

Within sixteen hours of his arrest, Unruh was taken to the New Jersey State Hospital at Trenton to be further evaluated. Through weeks of interviews, psychiatrists noted that Unruh “rarely spoke spontaneously” and was “at all times entirely free from anxiety or guilt.” He spoke in a monotone “with a marked degree of emotional flattening.” He never showed any emotion, even when the most delicate subjects were discussed—until asked about his attack on his mother, when he appeared to be guilty and fearful.

Some findings were surprising, if not lurid. Unruh had an unnaturally close relationship with his mother, though there was no evidence that it was sexual. He’d made sexual advances toward his brother as a youngster, but they were rebuffed. He started having sex with men during the service and continued after the war, and he struggled mightily with guilt over his behavior.

More to the point of his killings, there was little evidence that the insults Unruh imagined had ever really happened or, if they did, were as meaningful as he made them out to be. Maybe his neighbors

were

talking about him, but psychiatrists believed many of the insults Unruh “heard” were in his imagination. Either way, he was unable to laugh off a practical joke or a friendly jab and walk away; his paranoia simply wouldn’t let him.

And although his family disagreed, several psychiatrists found no link between Unruh’s war experiences and his ultimate unraveling. Unruh wasn’t psychologically right before the war, they said, and while combat certainly didn’t help, his slow decay was set in motion long before he ever fired a shot in anger.

A month after the shootings, the hospital’s staff declared Unruh to be suffering from a case of paranoid and catatonic schizophrenia that was slowly getting worse. In short, Howard Barton Unruh was insane, even if he understood his actions were wrong, and he would only get worse as time passed.

“He knew what he was doing,” the psychiatrists concluded, “but seemed to be operating from an automatic compulsion to continue shooting and killing until his ammunition was exhausted….

“His narcissism is such that at all times he has felt justified in the killings of the particular people whose murders he plotted from the beginning. [He] has always acknowledged that it was wrongful and has usually stated that he should die in the electric chair. He has shown himself totally unable to identify emotionally with the victims of his crime or to sense in any way the reactions directed against him by the survivors.”

Howard Unruh would never stand trial on thirteen counts of murder. He would never face the electric chair. He wouldn’t even face his accusers in a court of law.

Instead, DA Cohen announced that Unruh would be committed to the New Jersey State Hospital at Trenton where “he and the community will be protected from injury or danger should there be a recurrence of his homicidal impulses.”

For some, that wasn’t enough. A judge ordered Howard’s estranged father, Samuel, to pay the state of New Jersey $15 a month for his son’s care at the asylum.

And just in case Howard Unruh should ever be “cured,” the indictments against him would stand for decades.

A SUITCASE OF MEMORIES

While the world fascinated itself with the enigmatic and diseased mind of Howard Unruh, it overlooked young Charles Cohen.

Death had rubbed a callus on the heart of postwar America. A million Americans were killed or wounded in the war. Everyone else was simply lucky.

Thus it was with Charles. He’d lost his entire family to a madman’s fury, but because he suffered no physical wounds, he was “lucky.” So the wise men of science gathered ’round the maniac and sent the lucky little boy home.