Delivered from Evil: True Stories of Ordinary People Who Faced Monstrous Mass Killers and Survived (7 page)

Authors: Ron Franscell

Tags: #True Crime

So Brent excused himself and led Barton to All-Tech’s main office, where Brent’s partner, Scott Manspeaker, and administrative assistant Kathy Van Camp were working. Barton closed the door behind them, the same quirky smile still on his face. Brent turned to face Barton, who was standing just a couple feet away, suddenly breathing hard. The smile faded and Barton fixed a vacant glare on Brent.

“What’s up?” Brent asked.

Barton’s voice was suddenly ominous.

“Today is gonna be visual.”

DARK SECRETS

All-Tech opened in 1997, a child of the blossoming Internet’s perfect marriage to the dot-com boom. Its business plan was simple: provide the training, workspace, and technology so that adventurous investors could buy and sell stocks online throughout the day, banking on big profits in the minutes—sometimes seconds—that they owned them. The advent of personal computers, high-speed phone lines, and the Internet had destroyed the conventional wisdom that investors should ride out swells and troughs in the market by holding securities for long periods. Now anyone sitting at a well-connected computer could instantly buy and sell thousands of dollars worth of securities with a single mouse click.

In less time than it would take Buckhead baristas to make a double-shot cappuccino, daring day traders could make themselves rich—or lose a fortune. Dot-com stocks commonly catapulted 500 percent in a single day. It was the Wild West on a new frontier, where frothy dreamers, gamblers, and quick-draw artists all sought their fortunes in a lawless landscape. All they needed was a fast computer and a sense of adventure. And day-trading firms like Brent Doonan’s All-Tech snagged a piece of the action by charging commissions on all transactions and fees for using their broadband connections and state-of-the-art computers.

For Brent, launching All-Tech had been a nerve-racking investment. The former All-American athlete and high school honor student from the Kansas heartland had a degree in finance from Indiana University and was working for a Big Six accounting firm in Chicago when his sister’s boyfriend, Scott Manspeaker, pitched the idea of opening a day-trading firm. Carefully weighing the risks and rewards, Brent wrestled with the idea for months. Barely out of college, he felt it all seemed bigger than him, but he eventually embraced the idea enough to take out a daunting quarter-million-dollar business loan and move to Atlanta, where he and Manspeaker felt they could make the most money.

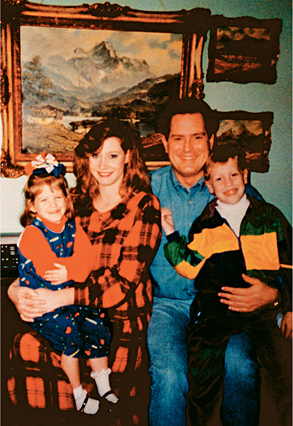

FOR ALL OUTWARD APPEARANCES, MARK BARTON WAS A DEVOTED FAMILY MAN, BUT AFTER HIS DEADLY 1999 RAMPAGE IN ATLANTA, A MUCH DARKER PORTRAIT OF A CONTROLLING, OBSESSIVE, AND ANGRY MAN EMERGED. HE’S SHOWN HERE WITH HIS WIFE LEIGH ANN, HIS DAUGHTER MYCHELLE, AND HIS SON MATTHEW.

Getty Images

Despite his youth, Brent was a driven competitor, mature beyond his years. He hated losing, and he’d do whatever it took to succeed. Very quickly, he was working seventy-hour weeks, and the money started to roll in.

Among Brent’s first and most enthusiastic customers was Mark O. Barton, a gregarious, fortysomething family man who lived in a manicured, middle-class neighborhood, went to church every Sunday, led his son’s Cub Scout troop, and appeared to skate through life with an imperturbable wit. Even at 6 feet, 4 inches and 250 pounds (2 meters and 113 kilograms), he appeared to be a gentle, if occasionally puckish, soul. A bright but socially invisible student, he held a college degree in chemistry and claimed to be working on a revolutionary new soap formula that would soon make him rich.

Barton traded with zeal. Where other day traders were cautious, Barton was aggressive. In 1998 and 1999, as the stock market was piling up unprecedented gains, his buddies called him “the Rocket” because his high-rolling successes launched him into wild celebrations. Wagering up to a quarter million dollars per session, Barton once scored a $106,000 profit in a single day.

The affable Barton seemed to always be smiling, even on his inevitable bad days. Brent grew to like him and enjoyed having him around. The usually sunny Barton was good for business.

But Barton’s smile hid dark secrets.

GETTING AWAY WITH MURDER

Barton had been a bright public school student, especially in chemistry and math, but he was also a misfit. He had no friends in school, much less girlfriends. He rebelled against his disciplinarian father by elaborately planning petty crimes and ingenious getaways, increasingly convinced he was a criminal mastermind, a natural schemer who was smarter than the average thug—until he got caught burglarizing a local drugstore at age fourteen.

Fascinated by chemistry, Barton began to experiment with homemade drugs. One frightening overdose landed him in the hospital, and a counselor said he withdrew further. He began to fear demons coming through the floor and had other delusions, so he was treated with antipsychotic drugs. At one point, Barton completely lost his ability to read, shaved his head, and plunged briefly into a strange religious fanaticism that isolated him even more.

Though he was a National Merit Scholarship semifinalist, Barton drifted after high school. Dropping out of Clemson University after only a semester, he eventually enrolled at the University of South Carolina, where he majored in chemistry—and began making and selling methamphetamine. He was arrested again for another drugstore break-in, but given probation.

After graduating in 1979, he married a college classmate, Debra Spivey, and took a series of dead-end jobs until he was hired as a chemist at a small Texarkana, Texas, chemical dealer. He eventually became the company’s operations manager, but in 1990 when his behavior became intolerably erratic and malicious, he was fired.

A week after the firing, someone broke into the company’s office and stole confidential formulas and financial data before completely disabling the office computers. After Barton was arrested and charged with the crime, he cut a deal with his former employer that let him go free if he returned the stolen material and left Texas forever. He was never prosecuted. His first ingenious getaway.

Barton fled to Georgia with his wife, Debra, and their toddler son, Matthew. He got a job as a chemical salesman. But soon after his daughter Mychelle was born in 1991, his marriage was in trouble. His affair with a young receptionist named Leigh Ann Lang had started three days after he met her. They flirted openly at work and were inseparable at after-hours parties with their colleagues.

The quarrels began. Debra accused her husband of infidelity and he denied it—even as he was secretly buying a $600,000 life insurance policy on his wife. More ominously, in June 1993, Barton told some of his mistress’s friends that he loved her more than he’d ever loved anyone, and that by October he’d be able to marry Leigh Ann. Was a divorce from Debra imminent?

On Labor Day weekend in 1993, Debra and her mother left Mark home with the kids and rented a small trailer at an Alabama campground. On Sunday, police found their viciously hacked corpses in the trailer, both virtually unrecognizable. The killer had literally split Debra’s skull in half with a small ax and battered her face with almost twenty more blows, splattering blood, flesh, and brains on the walls and curtains. Her mother had also been bludgeoned about ten times. Some cash was missing, but the sheer brutality suggested to cops this wasn’t a simple robbery gone bad.

There was more: Before fleeing, the enraged killer vomited on the floor and in the toilet, a sign that the intruder was ultimately sickened by what he’d done—more evidence that he was known to his victims.

One witness told police he’d seen a man fitting Barton’s description at the campground, and investigators later found traces of blood in Barton’s car and

splashed on his kitchen wall and sink, as if someone had washed blood from his hands. Barton refused to take a polygraph test about his whereabouts that night, and even before his dead wife was buried, he told relatives he intended to marry his mistress Leigh Ann, who was still married at the time.

But forensics failed to find any conclusive link between the stains and the murder, and a series of other errors doomed the investigation from the start. Yes, cops found blood on the ignition switch and a seat belt of Barton’s Ford Taurus. Barton couldn’t explain how it got there; instead, he brazenly challenged investigators: “If there is a ton of blood in my car, why aren’t you arresting me? Why am I not in handcuffs?”

Ultimately, no one would ever be charged, and the suspicious insurance company reluctantly settled Barton’s insurance claim for $450,000—insisting that $150,000 be set aside in trust funds for the children.

A week later, Leigh Ann moved in with Barton and his kids.

Barton’s behavior went quickly from

weird to worse. He killed his eight-year-old

daughter’s kitten, then took her to

search for her “lost” pet.

And within a few weeks of the murder, Debra and her mother were finally buried after a small, private funeral. During the services, Barton sat in the last pew, expressionless. When the ceremony ended, he hurried out the doors ahead of the other mourners, skipping the burial. Outside, Leigh Ann was waiting in her Mustang convertible, the stereo blaring.

Barton jumped in and they sped away in a cloud of Georgia suspicion. His second ingenious getaway.

Barton and Leigh Ann left their jobs together a year after the murder and married in 1995, but it wasn’t a peaceful union. They often bickered, and Leigh Ann would usually move out for a few days before they would reunite and begin the whole sordid cycle again.

In 1994, Barton’s three-year-old daughter, Mychelle, told her babysitter that her father had sexually molested her. No charges were ever filed, but Barton was ordered to undergo mental evaluations in which a court-appointed psychologist described him as “certainly capable” of murder.

From there, the Bartons’ miserable cycle of dysfunction only continued to spiral out of control. Leigh Ann would move out, then move back in. Barton ordered his wife not to answer the phone when he wasn’t home and exerted strict control over everything she did. She grew distant and cold, sometimes taking the children away from him for days. His get-rich-quick day-trading was burning through Debra’s insurance money at a startling rate. Barton

sometimes won big, but he’d usually lose it all within a few days. When the insurance money was gone, he sold the family furniture in yard sales to feed his habit. But to the outside world, he continued to behave as if the losses made no difference at all.

In October 1998, Leigh Ann left, supposedly for good. He became obsessed with his computer. One of his online profiles listed his hobbies as guns and day-trading, and his favorite quote was Dirty Harry’s taunting, “Go ahead, make my day.” Barton’s behavior went quickly from weird to worse. He killed his eight-year-old daughter’s kitten, then took her to search for her “lost” pet. Meanwhile, his obsession with day-trading grew more desperate.

Like so many times before, Leigh Ann relented. Only twenty-seven, she allowed Barton, now forty-four, to move into her two-bedroom apartment in the Atlanta suburb of Stockbridge because she missed the children.

But it was already too late. Mark Barton had lost control. He visited a minister and told him about his night terrors, his addiction to day-trading, and his fear that he’d inherited “mental imbalances” from his authoritarian father. His fragile hold on reality was being overwhelmed by his demons.

Over the next few desperate months, Barton would lose more money he didn’t have. In early June, when All-Tech cut him off for an unpaid $30,000 shortfall in his account, he simply walked across the street to Momentum Securities, another day-trading outfit, and plunked down a fresh $87,500 to start trading again. When he lost it, he borrowed another $100,000 from Momentum. Within a few weeks, he owed Momentum more than $120,000 and was so deep in the red that his trading was halted on July 27, 1999.

His escape route had been blocked. Too many people were standing between Mark Barton and one last ingenious escape. Brent Doonan was one of them.

“I REALLY WISH I HADN’T KILLED HER”

That night, after a Cub Scout den meeting, Barton and Leigh Ann fought again about money.

So he killed her.

Sometime in the wee hours, he bludgeoned her to death with a hammer as she slept. He wrapped her bloody corpse in a blanket and stuffed it behind some boxes in the bedroom closet so the children wouldn’t see her. He placed a note on her body: “I give you my wife, Leigh Ann Barton, my honey, my precious love. Please take care of her. I will love her forever.”

The next night, he also bashed in the heads of his son, Matthew, age eleven, and daughter, Mychelle, age eight, as they slept in the next room. To make sure they died, he placed them facedown in a bathtub full of water. Then he dried them off, wrapped their little bodies in comforters and laid them side by side in a bed, a stuffed teddy bear on Mychelle’s body and a Game Boy on Matthew’s.

Also on each was a handwritten note expressing love for “my son, my buddy, my life” and “my daughter, my sweetheart.” With only their still faces showing from the blankets, they appeared to be sleeping.