Delphi Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Illustrated) (712 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Illustrated) Online

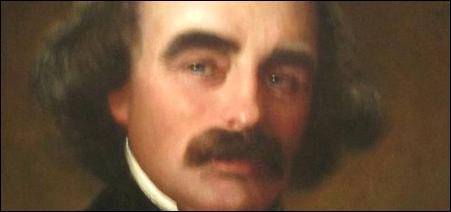

Authors: NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

Sentiment and humor do not lie so near the surface in Hawthorne as in Irving. He had a deep sense of the ridiculous, well shown in such sketches as “P's Correspondence” and “The Celestial Railroad”; or in the description of the absurd old chickens in the Pyncheon yard, shrunk by in-breeding to a weazened race, but retaining all their top-knotted pride of lineage. Hawthorne's humor was less genial than Irving's, and had a sharp satiric edge. There is no merriment in it. Do you remember that scene at the Villa Borghese, where Miriam and Donatello break into a dance and all the people who are wandering in the gardens join with them? The author meant this to be a burst of wild mænad gaiety. As such I do not recall a more dismal failure. It is cold at the heart of it. It has no mirth, but is like a dance without music: like a dance of deaf mutes that I witnessed once, pretending to keep time to the inaudible scrapings of a deaf and dumb fiddler.

Henry James says that Hawthorne's stories are the only good American historical fiction; and Woodberry says that his method here is the same as Scott's. The truth of this may be admitted up to a certain point. Our Puritan romancer had certainly steeped his imagination in the annals of colonial New England, as Scott had done in his border legends. He was familiar with the documents — especially with Mather's “Magnalia,” that great source book of New England poetry and romance. But it was not the history itself that interested him, the broad picture of an extinct society, the

tableau large de la vie

, which Scott delighted to paint; rather it was some adventure of the private soul. For example, Lowell had told him the tradition of the young hired man who was chopping wood at the backdoor of the Old Manse on the morning of the Concord fight; and who hurried to the battlefield in the neighboring lane, to find both armies gone and two British soldiers lying on the ground, one dead, the other wounded. As the wounded man raised himself on his knees and stared up at the lad, the latter, obeying a nervous impulse, struck him on the head with his axe and finished him. “The story,” says Hawthorne, “comes home to me like truth. Oftentimes, as an intellectual and moral exercise, I have sought to follow that poor youth through his subsequent career and observe how his soul was tortured by the blood-stain.... This one circumstance has borne more fruit for me than all that history tells us of the fight.” How different is this bit of pathology from the public feeling of Emerson's lines:

Spirit that made those heroes dare

To die and leave their children free,

Bid Time and Nature gently spare

The shaft we raise to them and thee.

s

Frank Preston Stearns (1846-1917), the son of abolitionist George Luther Stearns, was a writer from Massachusetts during the 19th century. In addition to collaborating in ambitious abolitionist projects, such as the

American Anti-Slavery Society, he is credited with several seminal works exploring the lives and careers of important American public figures and authors, including this detailed study of Hawthorne’s life, first published in 1906.

To Emilia Maciel Stearns

“In the elder days of art

Builders wrought with greatest care

Each minute and unseen part, —

For the gods see everywhere.”

—

Longfellow

“Oh, happy dreams of such a soul have I,

And softly to myself of him I sing,

Whose seraph pride all pride doth overwing;

Who stoops to greatness, matches low with high,

And as in grand equalities of sky,

Stands level with the beggar and the king.” —

Wasson

CONTENTS

SALEM AND THE HATHORNES: 1630-1800

BOYHOOD OF HAWTHORNE: 1804-1821

PEGASUS AT THE CART: 1839-1841

HAWTHORNE AS A SOCIALIST: 1841-1842

CONCORD AND THE OLD MANSE: 1842-1845

“MOSSES PROM AN OLD MANSE”: 1845

FROM CONCORD TO LENOX: 1845-1849

THE LIVERPOOL CONSULATE: 1852-1854

HAWTHORNE IN ENGLAND: 1854-1858

The simple events of Nathaniel Hawthorne's life have long been before the public. From 1835 onward they may easily be traced in the various Note-books, which have been edited from his diary, and previous to that time we are indebted for them chiefly to the recollections of his two faithful friends, Horatio Bridge and Elizabeth Peabody. These were first systematised and published by George P. Lathrop in 1872, but a more complete and authoritative biography was issued by Julian Hawthorne twelve years later, in which, however, the writer has modestly refrained from expressing an opinion as to the quality of his father's genius, or from attempting any critical examination of his father's literary work. It is in order to supply in some measure this deficiency, that the present volume has been written. At the same time, I trust to have given credit where it was due to my predecessors, in the good work of making known the true character of so rare a genius and so exceptional a personality.

The publication of Horatio Bridge's memoirs and of Elizabeth Manning's account of the boyhood of Hawthorne have placed before the world much that is new and valuable concerning the earlier portion of Hawthorne's life, of which previous biographers could not very well reap the advantage. I have made thorough researches in regard to Hawthorne's American ancestry, but have been able to find no ground for the statements of Conway and Lathrop, that William Hathorne, their first ancestor on this side of the ocean, was directly connected with the Quaker persecution. Some other mistakes, like Hawthorne's supposed connection with the duel between Cilley and Graves, have also been corrected.

F. P. S.