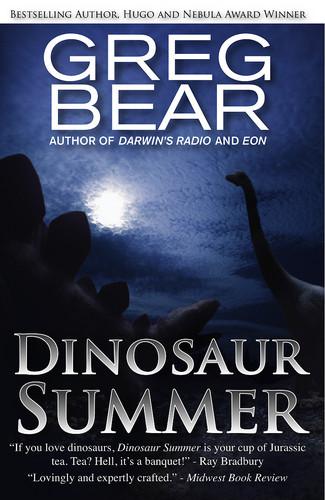

Dinosaur Summer

Authors: Greg Bear

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Science Fiction, #Adventure

For all who have brought dinosaurs back to life-- paleontologists, explorers, artists, moviemakers, animators, writers, and young minds everywhere.

--G. B.

The illustrations herein are dedicated with much admiration and respect to my mother and father, who allowed me to paint Tyrannosaurus Rex on my bedroom wall when I was nine years old.

And for Ray Strassburger, my fifth-grade teacher, who knew a seed when he saw one.

--T. D.

Acknowledgments

My special thanks go to Phil Currie, Michael Ryan, and the staff of the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta, Canada; to Karen Anderson, Kathleen Alcala, and Astrid Anderson Bear; and to my children, Erik and Alexandra, both of whom contributed animal ideas and listened to portions of the manuscript.

I owe a debt of gratitude as well to Ray Harryhausen, for partaking of this adventure; to Ron Borst and George E. Turner for information on Merian C. Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack; to Bill Warren; and to Dan Garrett, for enthusiastic footwork in Los Angeles.

I thank also the estate of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, for keeping his works alive and available.

I cannot begin to list all the other artists, paleontologists, authors, animators, etc.; instead, I reemphasize the dedication.

--G. B.

I would like to thank Charlie McGrady at CM Studio for supplying the wonderful dinosaur models used in the paintings for this book.

I would also like to thank William Stout for his warm support and inspiration, and for bringing dinos back to life in my imagination via his delicious art. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

--T. D.

BOOK

ONE

June 1947

Chapter One On the last day of school, after walking to the old brownstone building on 85th where they had an apartment, Peter's father told him that they would be going away for a few months. Peter gave him a squint that said,What, again?

The mailbox in the lobby was empty. Peter had been hoping for a letter from his mother. She had not written in a month.

They walked up the three flights of stairs in the hallway that always smelled of old shoes and mice--the polite word for rats--and his father said, "You think I'm going to take you to North Dakota or Mississippi or someplace, don't you?"

"It's happened," Peter said.

Anthony Belzoni gave his son a shocked look. "Would I do that to you--more than once?"

Sad that there had been no letter in the box and that school was over, Peter was in no mood for his father's banter, but he tried to sound upbeat. "We could go to Florida," he said hopefully. He loved Florida, especially the Everglades. His father had sold two articles toHoliday on travel for wealthy folks in the Everglades and resorts in the Keys, and they had lived well for several months after Anthony had been paid-- promptly, for once.

"Florida," Anthony said. "I'll keep it in mind." At the end of the dark hallway, a window let in sky-blue light that shone from the old, scuffed floors like moonglow on a faraway desert. The ceiling's patchy Lincrusta Walton tiles reminded Peter of a puzzle left unfinished by giants. "Did we stay here the whole year, instead of moving?"

"Yes," Peter said grudgingly. "Until now."

"So, what did you think of Challenger High?"

"Better than last year." In fact, it was the best school he had attended, another reason to want to stay.

"Do you know who Professor Challenger was?"

"Of course," Peter said. "He found living dinosaurs."

They reached the door and Peter took out his key and unlocked the deadbolt. Often enough, Peter came home alone, returning to an empty apartment. The door opened with a shuddering scrape. The apartment was warm and stuffy and quiet, like the inside of a pillow. Peter dumped his book bag on the swaybacked couch and opened a window to let in some air from the brick-lined shaft.

"I've been saving something to show you," Anthony said from the kitchen.

"What?" Peter asked without enthusiasm.

"First, I have a confession to make."

Peter narrowed his eyes. "What sort of confession?"

"I got a telegram from your mother. Last week. I didn't bother to tell you--"

"Why?" Peter asked. "It was addressed to me." Anthony returned to the front room and pulled the crumpled piece of paper from his shirt pocket. "She's worried about you. Summer's here. She thinks you're going to catch polio in all these crowds. She forbids you to swim in municipal pools."

There had been talk of a bad polio season in the newspapers and at school for months. Everyone was worried about putting their children together with other children.

Peter had hoped his mother might have sent a message inviting him to come to Chicago for a visit. "Oh," he said.

"She's practically ordering me to get you out of town. It's not a bad idea."

"Oh," Peter said, numb.

"And then, there's the prodigy," Anthony said, stepping back into the kitchen. He assumed a thick and generally faithful Bela Lugosi accent. "A sign looming over us both, like a . . . like a--"

"Forewarning," Peter said pessimistically.

"An auspice," Anthony countered cheerfully, switching to a kindly but menacing Boris Karloff lisp. He rattled the cans, one or two of which would probably be dinner. "Like a red sky at night."Red sky at night, sailor's delight.

"Aportent, " Peter said. Peter delighted in words, though he had a difficult time putting them together into narratives. His father, on the other hand, preferred living facts, yet could spin a yarn--or write a compelling piece of journalism--as easily as he breathed.

More cans rattled, then he heard Anthony dig into the bag of onions. That meant the canned goods were not up to expectations. Dinner would be fried onions and macaroni, not Peter's favorite. He missed good cooking.

"Why does it have to be a portent?" Anthony asked, standing in the kitchen doorway and tossing an onion in one hand.

"A foreboding," Peter continued. "An omen." He realized he sounded angry.

The slightest breath of warm wind ruffled the curtains at the window.

"Really." Anthony let the onion lie where it fell in his palm, balanced by his long, agile fingers.

Peter did not want to cry. He was fifteen and he had sworn that nothing would ever make him cry once he had reached twelve, but he had broken that vow several times since in private.

"You're angry because she didn't ask you to come to Chicago, and because there's no letter for you," Anthony said.

Peter turned away. "Show me your prodigy," he said.

"Your mother never did write letters, even when I was in Sicily."

"Just show me," Peter said too loudly.

Anthony looked down at the onion and pulled back a dry brown shred. Black dust sifted to the worn, faded carpet. "This one's rotten," he said. "You know about pizza? I ate my first pizza in Sicily. There's a restaurant called Nunzio's about six blocks from here where they serve them." "We don't have anymoney, " Peter said.

"Which shall it be first, the prodigy, or a pizza at Nunzio's?"

Peter realized his father was not kidding. Some other kids at school--the ones whose parents had money, whose fathers had regular jobs and could afford to take their families out to eat; fathers who still had wives, and kids who still had mothers living with them--had mentioned eating pizzas. "The omen," Peter said, staring out the window at the brick wall, waiting until his father wasn't looking to wipe his eyes. "Then pizza."

His father put a hand on his shoulder and Peter remembered how light Anthony's step was, like a cat. His father was tall and lean and had a long nose and walked silently, just like a cat.

"Come with me," Anthony said. They went past the kitchen, down a hall that led to a small bedroom behind the kitchen and the cramped white-tiled bathroom. The sound of groaning pipes followed them.

Peter slept on the couch in the living room and Anthony had a single bed in the small bedroom. This was not a bad apartment, Peter knew. It was certainly better than the one they had lived in last year in Chicago. That had been a real dump. But the brownstone building was old and dark and in warm weather the hallways smelled, and sometimes men peed in the lobby at night. Peter would have loved to live in the country, where, if people peed on the grass or on a tree, it didn't smell for days.

They entered the bedroom. A bright polished steel camera lay disassembled on a blue oilcloth on the narrow unmade bed. Clothes hung on the back of the tiny desk chair like the shed skin of a ghost. Books had been stacked in random piles under the window and against the wall. Two battered cardboard boxes in the one corner carried polished slabs of rock with beautiful patterns. The heavy rocks had burst the seams.

Some months ago, in the worst of his anger and boredom, after drinking half a bottle of Scotch, Anthony had carved a rude poem with his pocketknife in the plaster wall above the dresser. He had later covered it with a framed Monet print. Anthony was often an angry man; it was one of the reasons Peter's mother had left him. Leftthem.

Anthony tapped the wooden door above the bedstead. In the building's better days, the door had once concealed a dumbwaiter--a small elevator between floors. It had been painted over so many times that it had been glued shut. Peter had once tried opening it when his father was out, and could not.

Now, Anthony tapped it with his graceful hands and spread his fingers wide like a magician. "Voil� he said. The small door opened with a staccato racket that vibrated the wall and tilted a picture of his father's Army buddies.

Behind lay an empty shaft. The elevator was either in the basement or had vanished long ago. There were no ropes to pull to bring it up.

"Maybe it's not a dumbwaiter at all. Maybe it was a laundry chute," Anthony said. Peter was not impressed.

"What's in there that's so great?" Peter asked.

"Have you been dreaming of large animals?" Anthony asked with a funny catch in his voice. "No," Peter said.

"I have. Sleeping right here, in this bed, I've dreamed of very large animals with scaly skin and huge teeth and the biggest smiles."

Peter wondered what else his father had dreamed about, on those nights he came home and drank himself to sleep. He sniffed. "Why should I dream about them, just because you do?"

"Peter, my lad, loosen up. This is a real marvel." Anthony reached to the back of the shaft and pulled on a board. The board came away with a small squeak, revealing smooth dark stone beyond. Anthony put the board aside. He lifted a flashlight off the shelf beside the bed, bumped its end against the palm of his hand, and switched it on. "Where we're going this summer means I'll make enough money for us to live comfortably for at least a year."

"What about Mom?" Peter asked.

"Her, too," Anthony said a little stiffly. "Look." He handed Peter the flashlight and Peter shined it into the shaft, playing the beam over the dark slab of stone. A ghostly plume of cool air descended the shaft. Outside, the building was covered with soot, dark gray or almost black; here, the stone looked freshly cut, a rich dusty chocolate like the color of a high-priced lawyer's suit.Like the lawyer Mother hired.

The light caught a black shape pressed flat in the stone, a long irregular wedge with something sticking up out of it.

Peter's eyes widened. "It's ajaw, " he said. He got up onto the bed, knees sinking into the feather pillow, not bothering to remove his shoes. Anthony did not care about the shoes. Leaning into the shaft so that he could see all the way down, three floors, and all the way up, five more floors, Peter touched the dark thing embedded in the brownstone. "It's got teeth . . . like shark teeth."

"It's not a shark," Anthony said. "There are lots of fossils in brownstone. Brownstone is a kind of sandstone." Before the war, his father had worked as an apprentice coal and oil geologist in Pennsylvania. "Connecticut, late Triassic. A long time ago, animals died and washed down rivers until they settled into the sand and mud. They became fossils. I've heard of a bridge made of brownstone blocks that contains most of a dinosaur."

"Adinosaur? " Peter asked in disbelief.

"An old one. Not like the ones you see in circuses. Or rather, used to see."

"Wow," Peter said, and meant it, all his bad mood fled. "What kind is this?"

"I'm not sure," Anthony said. "Maybe a small meat-eater. Look at the serrations on that tooth. Like a steak knife."

"Whoever left it there, when they built this place, wascrazy, " Peter said.

"You know," Anthony said, "I've wondered about that. Fossils must have fetched a pretty penny when this building was made. But a stone mason, someone cutting and fitting all these blocks of stone, he sees this and shows it to the foreman, and the foreman tells the owner, and the owner, maybe he's superstitious . . . he thinks this building needs a guardian, something to protect it. He thinks maybe it's a dragon in the rock. So he says, `Everything's numbered and I don't want to have you cut a new piece. Put it up and leave it there.' And everybody shrugs and they set the block in place and leave it. The owner, he remembers where the block is, makes a note on the blueprints. He comes back after the building is done, finds the room, looks into the dumbwaiter shaft, pulls out this board . . . And there it is." Anthony smiled with great satisfaction. "I found it one night last week when I was bored. I couldn't sleep for all the dreams. I dug with my penknife at the paint around the door. Maybe I thought I'd crawl up into some pretty lady's bedroom. When I looked inside, I saw where a board in the back had been pulled loose. I tugged on it . . . voil�The board has been loose all this time."

"It's great," Peter said thoughtfully. "A building full of fossils."

"Maybe. We don't know there are any others."

"A whole riverbed full of skeletons," Peter said, his mind racing. "Maybe there was a flood and they all piled up, and there are dozens of them all around here, inside the stones."

"That would be fun," Anthony agreed.

Then Peter remembered. "So how is this an omen?"

Anthony sat on the edge of the bed. "The day after I found this, I got two letters, one from the Muir Society and another fromNational Geographic. You remember I sent my photos to Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor. He's the editor. He liked them, and he knows the director of the Muir Society. Conservationists."