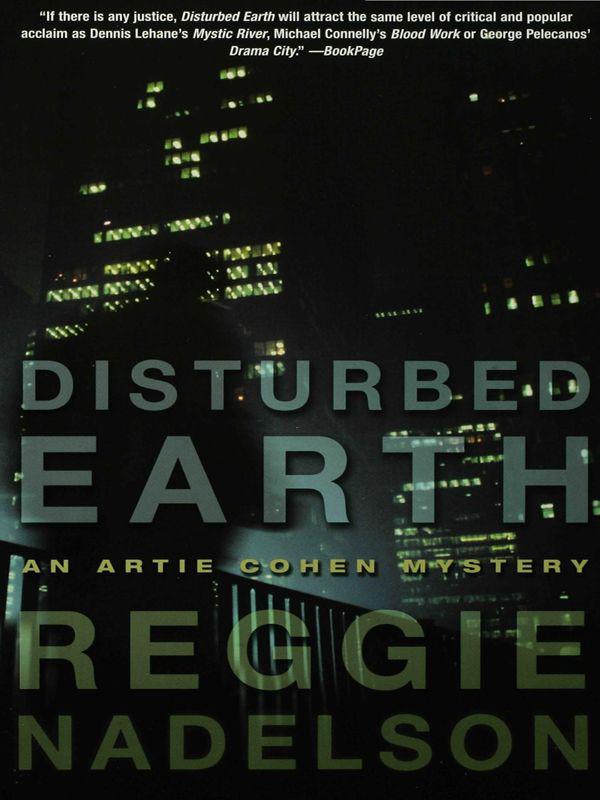

Disturbed Earth

Authors: Reggie Nadelson

Disturbed Earth

ALSO BY REGGIE NADELSON

Bloody London

Sex Dolls

Red Mercury Blues

Hot Poppies

Somebody Else

Comrade Rockstar

Disturbed Earth

Reggie Nadelson

Copyright © 2004 by Reggie Nadelson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Walker & Company, 104 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011.

All the characters and events portrayed in this work are fictitious.

Published in 2006 by Walker & Company

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Walker & Company are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Nadelson, Reggie.

Disturbed earth / Reggie Nadelson.

p. cm.

1. Cohen, Artie (Fictitious character)—Fiction. 2. Police—New York (State)—New York—Fiction. 3. New York (N.Y.)— Fiction. I. Title.

PS3564.A287DS72005

813'.54—dc22

2004065658

eISBN: 978-0-802-71855-6

First published in the United Kingdom in 2004 by William Heinemann

Published in the United States of America in 2005 by Walker & Company

This paperback edition published by Walker & Company in 2007

Visit Walker & Company's Web site at

www.walkerbooks.com

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

For Steven Zwerling and Rona Middleberg,

from Brooklyn

"Chapter One: He adored New York . . ."

Woody Allen,

Manhattan

If it hadn't been for the

The Queen of the Bay

being full, maybe it

would never have happened. As Billy watched the

Queen

slip out into

the water of Sheepshead Bay, he felt the faint breeze off the water, hot,

humid and salty, on his face, and listened to the voice of a fisherman

selling his catch, and the noise of customers bargaining, and the music

from a radio set down near the bucket offish. Billy could smell the

catch. Often he went home and his mother said he smelled offish, and

made him wash with soap and lemons. He shut his eyes tight and

stayed calm. This was important when things went wrong, like missing

the boat. He had learned it, at school, at home: you sealed yourself up

from the inside out and then they stopped bugging you and asking how

you felt and let you be, figuring you were OK.

He held tight to his half of the bag, feeling the rough canvas strap,

and the weight of the bag that he and Artie carried together. There was

bait in it they'd bought at the old bait and tackle shop overlooking the

inlet; there were sandwiches and sodas and the sweater his mother

made him bring though it was August and hot.

For weeks Billy had begged her to let him go out fishing at night.

He was almost twelve, he said. It would be OK. He made a list of

reasons he could and should go and he argued them so fiercely, she

finally said, OK, just this once, go on. It was because of the sheeps-head.

He had heard rumors that you could catch sheepshead best at

night. All summer he was crazy to see the fish that had given the place

its name and then disappeared decades ago, a fish, he had read, whose

mouth and teeth made it look like a sheep.

Up to now he had seen porgies, weakfish, blues, fluke, blacks, sea

bass, all the fish you could catch out here off the Brooklyn coast.

Sometimes he rode his bike from home to the docks and watched as men

cleaned fish from afresh catch. Sometimes they let him help.

He was interested in the boats, too, intent on learning their names.

Party boats, they called them in Brooklyn, and they went from seven in

the morning until three in the afternoon, or seven at night until three

in the morning, and though Artie had taken him on a morning boat

four times already that summer, this time they were going late. Billy

wanted to fish by moonlight. There was a picture of a fishing boat in

a book he had with the full moon making silver steps across the ocean;

it would be like that when they fished at night. When the

Queen

went

without them, he tried to stay calm, but he was having trouble, and a

kind of panicky feeling came up inside. Then he felt a tug on the

canvas bag.

He looked up at Artie, who said, come on, come on, let's run for it,

he said, gesturing at the boat in the next slip, and they ran and there

was just time and there was space on board. The boat was called

Just a Fluke,

and Artie explained it was a pun, a sort of joke, fluke being

both a common fish and a fluke also meaning a chance happening.

Like them being on this boat instead of the

Queen.

Afuke, Billy liked

the word.

A heavyset man with a smile Billy could see was fake, a smile just

plastered on his face that didn't mean anything, took their money. He

wore a battered old Brooklyn Dodgers baseball cap and told them it

was his boat, brand new, space for over a hundred people, but only half

full. His name was Stanley. Mr. Stanley, Billy thought. Mr. Stanley.

They fished all night, though you were only supposed to take two

fish and even thefuke had to be 17 inches, but the fat man in the

Dodgers cap let them keep extra, and they fished and ate salami

sandwiches and Billy thought nothing had ever tasted as good.

Around midnight, the storm boiled up out of nowhere. The

humidity rose even higher the way it sometimes did at night like steam

in a bathroom with the door closed. The sky got dark. The moon

disappeared. Out over the ocean lightning crackled up and zigzagged

across the sky like a zipper yanked open. Rain poured on them.

They laughed, him and Artie, laughed and laughed, soaked to the

skin. The boat returned early, and they got back to the pier still

laughing as rain came down in huge horizontal sheets, the wind

pushing it sideways.

Between them, each one with a hand on it and the other on his

fishing rod, the bag was heavy. It was full of empty soda cans and

sandwich bags and fish. They skidded over the wet planks of the dock,

and the bag fell. Fish spilled out. Artie tried to capture them, but they

slithered on the wet wood.

It's OK, Billy said, and pulled a net out of the bag, he always kept

a net, and tossed it over the fish and trapped them and laughed

gleefully. I've got them, he said. A man struggling with his own catch

saw them, and said to Artie, Is this your boy? Is this your son?

Artie said, no, he's my godson. Afterwards, when they were safe in

the car, Billy tugged his hand and said, very seriously, how come you

lied, and Artie said, What? You know you're my real father, he said,

and smiled. Come on, Artie, you know you're my real dad, and he

could see how happy Artie looked. Suddenly Billy knew he was in on

the game, too, pretending they were father and son.

Contents

A woman in a red fox coat walked down the boardwalk that was bleached white from snow and salt, a pair of large black poodles at the end of the leash in her hand. The wind whipped her backwards so the dogs seemed to pull her along as if on a sled. Above her the Parachute Drop, broken down, shut up, loomed against the winter sky, the Coney Island amusement park haunted by relics of its old dreams cape.

Inside Nathan's, as I passed, a trio of workers on the early shift, in their red Nathan's jackets, huddled together watching the cops outside. In the fluorescent light of the restaurant, I could see the faces of the three workers clearly; they had flat brown Indian faces, as if they'd come direct from some Andean village to the coast of America to serve up hot dogs dripping with yellow mustard. Like everyone in Brooklyn, they clung to their tribe; no matter how fragile or tiny it was, there was some kind of protection in it, or that's what I still thought that morning. One of them laughed suddenly. He flashed white teeth.

I'd been eating breakfast, key lime pie and coffee, in the city twenty minutes earlier when my phone rang and it was my boss, Sonny Lippert, at the other end.

"I need you."

"Tell me."

"It's a little girl," he said. "A child. They found some stuff a few hours ago."

Coney Island, he mumbled. You could see the old Parachute Drop from where they dumped it, you could see Nathan's, he said. Some slob probably eating hot dogs could have stopped it, but no one admitted seeing anything. They were all fucking blind, he yelled into the phone, they never see, they never tell, fucking monkeys, he added. They're piling on the sauerkraut and mustard and they don't fucking look out the window, you know, man? There's an empty stretch of ground out by the Key span Park where they play baseball now. Some jogger stumbled on it this morning. You with me? The stream of fury had poured into my ear, and I said, "OK, I'm coming, I'm there. OK?"

"Art?"

"Yeah, Sonny."

His voice cracked like, I was going to say cracked like a cold sore, but it didn't. It was never like that. In real life there were no metaphors; just dead people. His voice broke up; he was crying.

"I know she's dead. I can feel it."

"Feel what? Where's the body?"

But the line was bad and all I heard him say after that was, "Her shoes." Then the line broke.

All the time, while I drove from Manhattan out to Brooklyn, what lay just ahead, what Lippert had found out at Coney Island, was in my mind. I knew it was a child; I figured the kid was dead. Abused. Mutilated. It was everywhere, this thing with kids, the porn rings, the child abuse; babies were used, too, and you thought, who does this kind of thing? I thought of the killer in Boston who dug an underground tunnel and kept little girls in a row of cages. His sex slaves, he said. Some of them he kept for years. They clawed at the bars while they had energy, then, broken, just sat and waited for him.

You never got used to it, you got drunk, you got ulcers, you smoked yourself into a fog, you went crazy from stuff you saw. Any cop who gets used to it should quit.

I parked the car just beyond Nathan's and climbed up on the boardwalk and looked at the beach that stretched for miles along the Brooklyn coast. Beyond it was the ocean, the color of steel, and out on the horizon was a ship that looked like a toy. Wind blew off the water.

I walked a couple of hundred yards. Away from the ocean and the beach, on the other side of the boardwalk, was a stretch of waste ground; a couple of blue and whites, their lights flashing, were parked nearby. I ran down the steps from the boardwalk. The half-frozen ground was littered with junk, soda cans, used condoms, cigarette butts, syringes—the detritus of a Friday night. As I got closer I could see there was a hole in the ground, like an empty grave, cordoned off by yellow tape. Dead weeds were scattered on the mounds of earth beside it. While I watched, a black body bag was loaded onto a waiting EMS truck.

Near the hole in the ground stood two cops, like gravediggers, one male, one female, holding shovels, seeming to wait for an order. Move on. Dig some other place. Keep at it. But no one said it. It was like a play, no one moving, people looking down with the expressions frozen on their faces. Somewhere a siren wailed.

Suddenly, Sonny Lippert materialized from behind the EMS van.

"Art? Artie?"

As soon as he saw me, he started in my direction at about a hundred miles a minute, a human cannonball, compact, fast on his feet, pulling his little camel's hair coat close to him. Fast and tightly wrapped, Sonny was a small man.

"It's a serial," he said. "I knew it would happen, sooner or fucking later, I so goddamn knew."

"Who is she?"

He shook his head.

"I don't know. No one's claimed her. No one's reported a child missing anywhere in the area. What kind of people don't know their kid is missing, man?"

Lippert was probably sixty; he looked ten years younger. He used "man" every second word; when I first knew him, he thought of himself as a fifties hipster; he gave it up a while back, the clothes, the walk, except for the verbal tic. It made him sound weirdly young, now that "man" and "cool" fell out of the mouths of every wannabe hipster kid in every bar on the Lower East Side and Williamsburg.

"How old is she?" I said.

"They don't know."

"So make a guess."

Sonny said, "Ever since I started running this unit, I feel like I stepped in a sewer that has no bottom, just dropped down and all there is, is shit."

Lippert was at the head of a special unit that prosecuted cases involving kids: kidnapping, pedophiles, kiddie porn, priests—the country was littered with lousy priests. The whole miserable business had exploded in the last few years.

Kids were big business; they were cheap. You could get a kid for less than an adult, and it was global. And not just in Asia or some remote part of Africa where they stole children to be used as soldiers or slaves. In Eastern Europe you could buy a kid for sex for less than you could rent a car. You went to Teplice and other border towns—in the Czech Republic, not India, not Africa, in Europe—and people stood at the side of the highway and handed their own children down to men in cars. Little kids. Their own parents luring them with candy. Take the candy, darling, go with the nice man. I'd been there. I'd seen it.

In California last summer, two little girls were killed so brutally they never told the public the details. Couldn't. I heard from some friends there. I didn't think about it if I could help it. There had been so many kids abducted the last couple of years, so many high profile cases. Thousands of kids just disappeared. Tens of thousands. You saw the flyers on lampposts, you saw the milk cartons. Like dust scattering; like garbage; like insects. Just gone. Where did they go?

Lippert took on as much as he could and it was a lousy job. He had to keep everyone happy, the families, the local precincts, the local kidnap detectives, and some from homicide squads and the people at Police Plaza who also worked on child cases. He had been a cop and a federal prosecutor; he was a born politician and I didn't completely trust him, but I owed him and I'd made my peace with it.

He got me my first job as a cop after I graduated the academy. Said he talent spotted me, that's what he said when we were out together and a little bit drunk. I spoke a few languages; he said it was handy to have someone around who knew Russian, Hebrew, a little French, a little Arabic. Since his divorce he sometimes invited me to eat with him, at Peter Luger in Brooklyn because he loved the steak and hash browns, or at Rao's in Harlem; I went because he was the only person I knew who could get a table at Rao's, and because he liked me.

A beefy detective, a local who looked like he ate steroids with his Wheaties, glanced at me and I knew he was pissed off that Lippert was here and had called me out from the city. They were territorial in this part of Brooklyn, and I already had a reputation for interfering in cases involving Russians in Brighton Beach, a mile or so west along the coast. Lippert ignored him and pulled me towards the boardwalk, then leaned against the railing and for a second pressed his hand against his temple as if he had a migraine that nothing could fix.

"Christ," he said, and the horror he seemed to feel transmitted itself like disease; it wrapped itself around me and I hoped Lippert didn't ask me to look at the body.

Don't ask, I thought. Please don't ask. I can't do it. This got to me in a way few things did, this thing with kids. I thought about Billy Farone, my cousin's boy.

"I want you to look," Sonny said. "I want you to see."

Like a tugboat at my side, he ferried me to the van. He signaled to the EMS guy to remove the black rubber bag and place it on the ground. I waited, listening to the bang of the door, the snap of the latex gloves as the EMS guy pulled them on, the zipper. For me the sound of death wasn't a gun or the hot howl of fire at a crematorium or the thud of a coffin lowered into the earth; it was the sound of the zipper on a body bag.

"Look." He tossed me a pair of latex gloves and I put them on and bent over the clothes.

Inside the bag was a pair of green sneakers. So soaked in blood were the All Star high tops that only a scrap of green canvas showed. There was a kid's T-shirt that had been white and was smeared with blood. I picked it up by its edge and saw there were cuts across the front and back, as if it had been sliced from the kid's body with a razor. There were faded jeans. A blue baseball jacket, Yankees logo, also bloody. Saturated with blood, the blue of both garments looked dark, almost black. The left sleeve of the jacket was ripped.

"That's all?"

"It's enough," he said.

"What about the body?"

"There's no body, man," he said. "Habeas corpus. Not. You understand me?"

"What do you mean there's no body?"

He got agitated and kept repeating there was no body and it didn't matter.

"Calm down," I said. I had only seen Lippert like this a few times, but it happened. He got overloaded, he felt personally involved, he lost it.

"You don't even know she's dead," I said. "You don't even know who she is. You don't even know it's a girl. You're getting crazy, and about what?"

"Fuck you, man," he said. "Don't patronize me with that 'calm down' shit." He pushed me away from the others, pushed me with the flat of his hand against my chest. "I know is how I know I know. Twice before already this kind of thing happened, once about five years back when they found a kid's clothes first and then the body on Long Island, then around eighteen months ago, twenty, yeah, it was the summer before last, July maybe, I got a call, middle of the night, there were clothes, you understand me, there were kids' clothes and they were drenched in blood, just like this, in a hole in the ground out by Rockaway," he said and gestured towards the beach as it stretched west. "Then we found the body, a piece at a time. They had cut off her feet. They took off her sneakers and then her feet, and the feet floated up in the canal over by Sheepshead Bay. Somebody went fishing off a party boat and caught one. Enough? OK? You want more?" He stopped and caught his breath. "She was eight, and some piece of shit cut off her feet. Other parts. You want me to draw you a picture? It was, what, a couple miles from here? We found her eventually. I remember, there were sneakers then, the same kind of sneakers. Green high tops."

"I don't remember."

"You were in Bosnia or some other fucking place. Working private," he said and I knew he blamed me for leaving the job. When Lippert felt vindictive, he made it a moral thing; you worked just for money, you were a lousy human being. You had failed.

"You ever see parents ID their child, Art? You want to do that? You want to say to the mother, is this your kid with her feet missing? Her hands? Her face?"

The blood vessels in his face constricted; he turned a strange dark red, the color of pastrami.

"I knew it wasn't over. I knew he'd surface. They always do. They can't stop and I said, don't let it go cold, not this one, but they did and nobody worked cold cases over 9/11. The son of a bitch has started up again. I knew he was a serial."

"Or it's a copycat."

"The other cases have been out of the papers for too long for a copycat. Both cases. The one on Long Island, the one I worked out in Rockaway. But I know it's the same fucking bastard, and I'm going to get him fried this time. Fried and fried. If they let me stick the needle in myself, I'll do it and then I'll celebrate."

"Sonny?"

"Yeah?"

"Never mind."

"You were going to ask if they cut off her feet before or after?"

I didn't answer.

He said, "I don't know. I don't know when they did it." I could feel his breath.

"When they called me with this earlier," he said gesturing to the scene, "I figured we'd hear a little girl was missing, you know? Give me a cigarette, Art, OK?"

I fumbled in my jacket pocket and got a squashed pack of Marlboros and handed it to him. Sonny, who doesn't smoke, stuck one in his mouth and I lit it for him. The wind from the ocean blew out the match and I lit another one.

"I can't stand the smell," he said.

All I could smell was the fresh bright air and a faint taste of salt.