Do Penguins Have Knees? (23 page)

Read Do Penguins Have Knees? Online

Authors: David Feldman

The only problem with this technology is that it works best with monochrome images. The red and blue-green tints of the glasses add unwanted and unsubtle coloration to a color 3-D film.

The solution, Gibson is generous enough to admit, came from rival Polaroid, which developed, appropriately enough, a polarization method specifically for 3-D films. The Polaroid technology beams

the angle of polarization for one eye at right angles to that for the other eye, so that one image is transmitted while the other eye is blocked. This is the system used for the 3-D movies made in the 1950s.

Submitted by Don Borchert of Lomita, California

.

What

Use Is the Appendix to Us? What Use Are Our Tonsils to Us?

The fact that this Imponderable was first posed to us by a medical doctor indicates that the answer is far from obvious. We asked Dr. Liberato John DiDio this question, and he called the appendix the “tonsils of the intestines.” We wondered if this meant merely that the appendix is the organ in the stomach most likely to be extracted by a surgeon. What good are organs like tonsils and the appendix and gall bladder when we don’t seem to miss them at all once they’ve been extracted?

Actually, tonsils and the appendix do have much in common. They are both lymphoid organs that manufacture white blood cells. William P. Jollie, professor and chairman of the Department of Anatomy at the Medical College of Virginia at Virginia Commonwealth University, explains the potential importance of the appendix:

One type of white blood cell is the lymphocyte; it produces antibodies, proteins that distinguish between our own body proteins and foreign proteins, called antigens. Antibodies, produced by lymphocytes, deactivate antigens.

Lymphocytes come in two types: B-lymphocytes and T-lym-phocytes. T-lymphocytes originate in the thymus. There is some evidence to suggest that B-lymphocytes originate in the appendix, although there is also evidence that bone marrow serves this purpose.

If our appendix is so important in fighting infections, how can we sustain its loss? Luckily, other organs, such as the spleen, also manufacture sufficient white blood cells to take up the slack.

Some doctors, including Dr. DiDio, even suggest that the purpose of the appendix (and the tonsils) might be to serve as a lightning rod and actually attract infections. By doing so, the theory goes, infections are localized in one spot that isn’t critically important to the functioning of the body. This lightning-rod theory is supported, of course, by the sheer numbers of people who encounter problems with appendix and tonsils compared to surrounding organs.

Accounts vary on whether patients with extracted tonsils and/or appendix are any worse off than those lugging them around. It seems that medical opinion on whether it is proper to extract tonsils for mild cases of tonsillitis in children varies as much and as often as hemlines on women’s skirts. Patients in the throes of an appendicitis attack do not have the luxury of contemplation.

Submitted by Dr. Emil S. Dickstein of Youngstown, Ohio. Thanks also to Lily Whelan of Providence, Rhode Island, and George Hill of Brockville, Ontario

.

Where

Does the Moisture Go When Wisps of Clouds Disappear in Front of Your Eyes?

A few facts about clouds will give us the tools to answer this question:

1. A warm volume of air at saturation (i.e., 100 percent relative humidity), given the same barometric pressure, will hold more water vapor than a cold volume of air. For example, at 86 degrees Fahrenheit, seven times as much water vapor can be retained as at 32 degrees Fahrenheit.

2. Therefore, when a volume of air cools, its relative humidity increases until it reaches 100 percent relative humidity. This point is called the dew point temperature.

3. When air at dew point temperature is cooled even further, a visible cloud results (and ultimately, precipitation).

4. Therefore, the disappearance of a cloud is caused by the opposite of #3. Raymond E. Falconer, of the Atmospheric Sciences Research Center, explains:

As a volume of air moves downward from lower to higher barometric pressure, it becomes warmer and drier, with lower relative humidity. This causes the cloud to evaporate.

When we see clouds, the air has been rising and cooling with condensation of the invisible water vapor into visible cloud as the air reaches the temperature of the dew point. When a cloud encounters drier air, the cloud droplets evaporate into the drier air, which can hold more water vapor.

When air is forced up over a mountain, it is cooled, and in the process a cloud may form over the higher elevations. However, as the air descends on the lee side of the mountain, the air warms up and dries out, causing the cloud to dissipate. Such a cloud formation is called an orographic cloud.

Submitted by Rev. David Scott of Rochester, New York

.

Our correspondents reasoned, logically enough, that since both fresh and frozen orange juice are squeezed from oranges, and since the frozen juice must be concentrated, the extra processing involved would make the frozen style more expensive to produce and thus costlier at the retail level. But according to economists at the Florida Department of Citrus, it just ain’t so.

Although the prices of fresh fruit, chilled juice, and frozen concentrate are similar at the wholesale level (within two cents of the fresh fruit equivalent per pound), they depart radically at the retail level. In the period of 1987-1988, frozen concentrated orange juice cost 24.6 cents per fresh pound equivalent; chilled juice was 35 cents per fresh pound equivalent; and the fruit itself a comparatively hefty 58.5 cents per pound. Why the discrepancy?

In the immortal words of real estate brokers across the world, the answer is: location, location, location. Chilled juice (and the fresh fruit itself, for that matter) would cost less than frozen if it didn’t need to be shipped long distances. But it does. The conclusion, as Catherine A. Clay, information specialist at the Florida Department of Citrus, elucidates, is clearly that the costs at the retail level are due to distribution rather than processing costs.

One 90-pound box of oranges will make about 45 pounds of juice. Concentrating that juice by removing the water will reduce the weight by at least two-thirds, so the amount of frozen concentrate in one box would be about 15 pounds.

So you can ship three times as much frozen concentrated juice in one truck than you can chilled juice, and twice as much chilled juice as fresh oranges. In the space in which one 90-pound box of oranges is shipped, you could ship six times as much frozen concentrated orange juice.

In addition, fresh fruit can begin to decay or be damaged during transit to the retailer. So while the retailer may have paid for the entire truckload, he may have to discard decayed or damaged fruit. Yet his cost for that load remains the same regardless of how much actual fruit he sells.

Frozen concentrated juice does not spoil, so there is no loss. The higher price for fresh fruit would compensate the retail buyer for the cost of the lost fruit.

Clay didn’t add that many juice distributors who use strictly Florida oranges for their chilled juice use cheaper, non-American orange juice for their concentrated product. Why don’t they use the cheaper oranges for their chilled juices? Location. Location. Location. It would be too expensive to ship the heavier, naturally water-laden fruits thousands of miles.

Submitted by Eugene Hokanson of Bellevue, Washington. Thanks also to Herbert Kraut of Forest Hills, New York

.

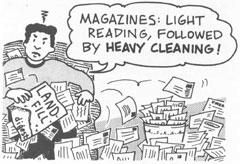

Fewer things are more annoying to us than receiving a magazine we put our soft-earned bucks down to subscribe to, and being rewarded for our loyalty by being showered with cards entreating us to subscribe to the very magazine we’ve just shelled out for.

Why is it necessary to have to clean a magazine of foreign matter before you read the darn thing? Because the cards work. Publishers know that readers hate them; but the response rate to a card, particularly one that allows a free-postage response, attracts more subscribers than a discreet ad in the body of the magazine.

Those pesky little inserts that fall out are called “blow-in cards” in the magazine biz. We thought “blow-out” cards might be a more descriptive moniker until we learned the derivation of the term from Bob Nichter, of the Fulfillment Management Association.

Originally, blow-in cards were literally blown into the magazine by a fan on the printer assembly line. Now, blow-ins are placed mechanically by an insertion machine after the magazine is bound. Nothing special is needed to keep the cards inside the magazine; they are placed close enough to the binding so that they won’t fall out unless the pages are riffled.

Why do many periodicals place two or more blow-in cards in one magazine? It’s not an accident. Most magazines find that two blow-in cards attract a greater subscription rate than one. Any more, and reader ire starts to overshadow the slight financial gains.

Submitted by Curtis Kelly of Chicago, Illinois

.

Anyone who has ever seen a child fidgeting, desperately struggling to keep a thermometer under the tongue, has probably wondered why this practice started. Why do physicians want to take our temperature in the most inconvenient places?

No, there is nothing intrinsically important about the temperature under the tongue or, for that matter, in your rectum. The goal is to determine the “core temperature,” the temperature of the interior of the body.

The rectum and tongue are the most accessible areas of the body that are at core temperature. Occasionally the armpit will be used, but the armpit is more exposed to the ambient air, and tends to give colder readings. Of course, drinking a hot beverage, as many schoolchildren have learned, is effective in shooting one’s temperature up. But barring tricks, the area under the tongue, full of blood vessels, is almost as accurate as the rectal area, and a lot more pleasant place to use.

So what are the advantages of putting the thermometer

under

the tongue as opposed to over it? Let us count the ways:

1.

Accuracy

. Placing the thermometer under the tongue insulates the area from outside influence, such as air and food. As Dr. E. Wilson Griffin III told

Imponderables

, “Moving air would evaporate moisture in the mouth and on the thermometer and falsely lower the temperature. It is important to have the thermometer under the tongue rather than just banging around loose inside the mouth, because a mercury thermometer responds most accurately to the temperature of liquids or solids in direct contact with it….”

2.

Speed

. The soft tissues and blood vessels of the tongue are ideal resting spots for a thermometer. Dr. Frank Davidoff, of the American College of Physicians, points out that compared to the skin of the armpit, which is thick, horny, and nonvascular, the “soft, unprotected tissues under the tongue wrap tightly around the thermometer, improving the speed and completeness of heat transfer.”

3.

Comfort

. Although you may not believe it, keeping the thermometer above the tongue would not be as comfortable. The hard thermometer, instead of being embraced by the soft tissue below the tongue, would inevitably scrape against the much harder tissues of the hard palate (the roof of your mouth). Something would have to give—and it wouldn’t be the thermometer.