Domes of Fire (27 page)

Authors: David Eddings

Then another man in black rode out from farther back in the trees. This one wore exaggeratedly dramatic

clothing. He had on a black, wide-brimmed hat and wore a black bag with ragged eye-holes over his head.

‘Has this all been some sort of joke?’ Tynian demanded. ‘Is that who I think it is?’

‘I’d guess that it’s the one in the robe who’s been in charge,’ Ulath said. ‘I doubt that Sabre could successfully herd goats.’

‘Savour thine empty victory, Anakha,’ the hooded figure called in a hollow, strangely metallic voice. ‘I did but test thee that I might discern thy strength – and thy weaknesses. Go thy ways now. I have learned what I needed to learn. I will trouble thee no further – for now. But mistake me not, oh man without destiny, we will meet anon, and in our next meeting shall I try thee more significantly.’ Then Sabre and his hooded companion wavered and vanished.

The wailing and groaning of the wounded enemies all around them suddenly broke off. Sparhawk looked around quickly. The strangely-armoured foot troops he and his friends had been fighting were all gone. Only the dead remained. Back along the road in either direction, Kring’s Peloi were reining in their horses in amazement. The troops they had engaged had vanished as well, and startled exclamations from back among the trees indicated that the Atans had also been bereft of enemies.

‘What’s going on here?’ Kalten exclaimed.

‘I’m not sure,’ Sparhawk replied, ‘but I

am

sure that I don’t like it very much.’ He swung down from his saddle and turned one of the fallen enemies over with his foot.

The body was little more than a dried husk, browned, withered and totally desiccated. It looked very much like the body of a man who had been dead for several centuries at least.

‘We’ve encountered it once before, your Grace,’ Tynian was explaining to Patriarch Emban. It was nearly morning, and they were gathered once again atop the rocky hill. ‘Last time it was antique Lamorks. I don’t know what kind of antiques these were.’ He looked at the two mummified corpses the Atans had brought up the hill.

‘This one is a Cynesgan,’ Ambassador Oscagne said, pointing at one of the dead men.

‘Looks almost like a Rendor, doesn’t he?’ Talen observed.

‘There would be certain similarities,’ Oscagne agreed. ‘Cynesga is a desert, much like Rendor, and there are only so many kinds of clothing suitable for such a climate.’

The dead man in question was garbed in a flowing, loose-fitting robe, and his head was covered with a sort of cloth binding that flowed down to protect the back of his neck.

‘They aren’t very good fighters,’ Kring told them. ‘They all sort of went to pieces when we charged them.’

‘What about the other one, your Excellency?’ Tynian asked. ‘These ones in armour were

very

good fighters.’

The Tamul Ambassador’s eyes grew troubled. ‘That one’s a figment of someone’s imagination,’ he declared.

‘I don’t really think so, your Excellency,’ Sir Bevier disagreed. ‘The men we encountered back in Eosia had been drawn from the past. They were fairly exotic, I’ll grant you, but they

had

been living men once. Everything we’ve seen here tells us that we’ve run into the same thing again. This fellow’s most definitely

not

an imaginary soldier. He

did

live once, and what he’s wearing was his customary garb.’

‘It’s impossible,’ Oscagne declared adamantly.

‘Just for the sake of speculation, Oscagne,’ Emban

said, ‘let’s shelve the word “impossible” for the time being. Who would you say he was if he

weren’t

impossible?’

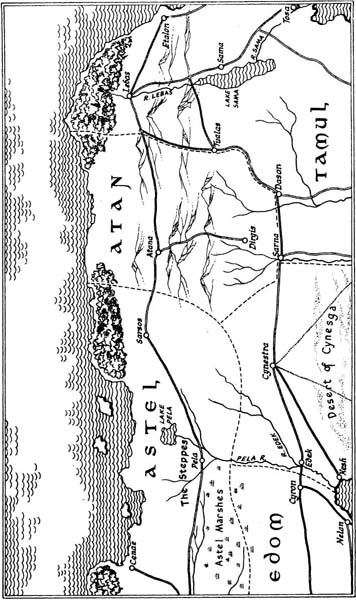

‘It’s a very old legend,’ Oscagne said, his face still troubled. ‘We’re told that once, a long, long time ago, there were people in Cynesga who pre-dated the current inhabitants. The legend calls them the Cyrgai. Modern Cynesgans are supposed to be their degenerate descendants.’

‘They look as if they come from two different parts of the world,’ Kalten noted.

‘Cyrga, the city of the Cyrgai, was supposed to lie in the central highlands of Cynesga,’ Oscagne told him. ‘It’s higher than the surrounding desert, and the legend says there was a large, spring-fed lake there. The stories say that the climate there was markedly different from that of the desert. The Cyrgai wouldn’t have needed protection from the sun the way their bastard offspring would have. I’d imagine that there were indications of rank and status involved as well. Given the nature of the Cyrgai, they’d have definitely wanted to keep their inferiors from wearing the Cyrgai costume.’

‘They lived at the same time then?’ Tynian asked.

‘The legends are a little vague on that score, Sir Tynian. Evidently there

was

a period when the Cyrgai and the Cynesgans co-existed. The Cyrgai would certainly have been dominant, though.’ He made a face. ‘Why am I talking this way about a myth?’ he said plaintively.

‘This is a fairly substantial myth, Oscagne,’ Emban said, nudging the mummified Cyrgai with his foot. ‘I gather that these fellows had something of a reputation?’

‘Oh, yes,’ Oscagne said with distaste. ‘They had a hideous culture – all cruelty and militarism. They held themselves aloof from other peoples in order to avoid what they called contamination. They were said to be

obsessively concerned with racial purity, and they were militantly opposed to any new ideas.’

‘That’s a futile sort of obsession,’ Tynian noted. ‘Any time you engage in trade, you’re going to encounter new ideas.’

‘The legends tell us they understood that, Sir Knight. Trade was forbidden.’

‘No commerce at all?’ Kalten asked incredulously.

Oscagne shook his head. ‘They were supposed to be totally self-sufficient. They even went so far as to forbid the possession of gold or silver in their society.’

‘Monstrous!’ Stragen exclaimed. ‘They had no money at all?’

‘Iron bars, we’re told – heavy ones, I guess. It tended to discourage trade. They lived only for war. All the men were in the army, and all the women spent their time having babies. When they grew too old to either fight or bear children, they were expected to kill themselves. The legends say that they were the finest soldiers the world has ever known.’

‘The legends are exaggerated, Oscagne,’ Engessa told him. ‘I killed five of them myself. They spent a great deal of time flexing their muscles and posing with their weapons when they should have been paying attention to business.’

‘The ancients were very formal, Atan Engessa,’ Oscagne murmured.

‘Who was the fellow in the robe?’ Kalten asked. ‘The one who seemed to be trying to pass himself off as a Seeker?’

‘I’d guess that he holds a position somewhat akin to Gerrich in Lamorkand and to Sabre in Western Astel,’ Sparhawk surmised. ‘I was a little surprised to see Sabre here,’ he added. He had to step rather carefully here. Both he and Emban were sworn to secrecy on the matter of Sabre’s real identity.

‘Professional courtesy, no doubt,’ Stragen murmured. ‘The fact that he was here sort of confirms our guess that all these assorted upheavals and disturbances are tied together. There’s somebody in back of all this – somebody we haven’t seen or even heard of yet. We’re going to have to catch one of these intermediaries of his and wring some information out of him sooner or later.’ The blond thief looked around. ‘What now?’ he asked.

‘How long did you say it would be until the Atans arrive from Sarsos, Engessa?’ Sparhawk asked the towering Atan.

‘They should arrive sometime the day after tomorrow, Sparhawk-Knight.’ The Atan glanced toward the east. ‘Tomorrow, that is,’ he corrected, ‘since it’s already starting to get light.’

‘We’ll care for our wounded and wait for them then,’ Sparhawk decided. ‘I like lots of friendly faces around me in times like this.’

‘One question, Sparhawk-Knight,’ Engessa said. ‘Who is Anakha?’

‘That’s Sparhawk,’ Ulath told him. ‘The Styrics call him that. It means “without destiny”.’

‘All men have a destiny, Ulath-Knight.’

‘Not Sparhawk, apparently, and you have no idea how nervous that makes the Gods.’

As Engessa had calculated, the Sarsos garrison arrived about noon the following day, and the hugely increased escort of the Queen of Elenia marched easterly. Two days later, they crested a hill and gazed down at a marble city situated in a broad green field backed by a dark forest stretching to the horizon.

Sparhawk had been sensing a familiar presence since early that morning, and he had ridden on ahead eagerly.

Sephrenia was sitting on her white palfrey beside the road. She was a small, beautiful woman with black hair,

snowy skin and deep blue eyes. She wore a white robe of a somewhat finer weave than the homespun she had normally worn in Eosia.

‘Hello, little mother,’ he smiled, saying it as if they had been apart for no more than a week. ‘You’ve been well, I trust?’ He removed his helmet.

‘Tolerable, Sparhawk.’ Her voice was rich and had that familiar lilt.

‘Will you permit me to greet you?’ he asked in that formal manner all Pandions used when meeting her after a separation.

‘Of course, dear one.’

Sparhawk dismounted, took her wrists and turned her hands over. Then he kissed her palms in the ritual Styric greeting. ‘And will you bless me, little mother?’ he asked.

She fondly placed her hands on his temples and spoke her benediction in Styric. ‘Help me down, Sparhawk,’ she commanded.

He reached out and put his hands about her almost child-like waist. Then he lifted her easily from her saddle. Before he could set her down, however, she put her arms about his neck and kissed him full on the lips, something she had almost never done before. ‘I’ve missed you, my dear one,’ she breathed. ‘You cannot believe how I’ve missed you.’

The carriage came around a bend in the road and approached the spot where Sparhawk and Sephrenia waited. Ehlana was talking animatedly to Oscagne and Emban, but she broke off suddenly, her eyes wide. ‘

Sephrenia?

’ she gasped. ‘

It is! It’s Sephrenia!

’ Royal dignity went out the window as she scrambled down from the carriage.

‘Brace yourself,’ Sparhawk cautioned with a gentle smile.

Ehlana ran to them, threw her arms around Sephrenia’s neck and kissed her, weeping for joy.

The queen’s tears were not the only ones shed that afternoon. Even the hard-bitten Church Knights were misty-eyed for the most part. Kalten went even further and wept openly as he knelt to receive Sephrenia’s blessing.

‘The Styric woman has a special significance, Sparhawk-Knight?’ Engessa asked curiously.

‘A very special significance, Atan Engessa,’ Sparhawk replied, watching his friends clustered around the small woman. ‘She touches our hearts in a profound way. We’d probably take the world apart if she asked us to.’

‘That’s a very great authority, Sparhawk-Knight.’ Engessa said it with some approval. Engessa respected authority.

‘It is indeed, my friend,’ Sparhawk agreed, ‘and that’s only the least of her gifts. She’s wise and beautiful, and I’m at least partially convinced that she could stop the tides if she really wanted to.’

‘She is quite small, though,’ Engessa noted.

‘Not really. In our eyes she’s at least a hundred feet tall – maybe even two hundred.’

‘The Styrics are a strange people with strange powers, but I had not heard of this ability to alter their size before.’ Engessa was a profoundly literal man, and hyperbole was beyond his grasp. ‘Two hundred, you say?’

‘At least, Atan.’

Sephrenia was completely caught up in the outpouring of affection, and so Sparhawk was able to observe her rather closely. She had changed. She seemed more open, for one thing. No Styric could ever completely lower his defences among Elenes. Thousands of years of prejudice and oppression had taught them to be wary – even of those Elenes they loved the most. Sephrenia’s defensive shell, a shell she had kept in place around her for so long that she had probably not even known it was there, was gone now. The doors were all open.

There was something more, however. Her face had been luminous before, but now it was radiant. A kind of regretful longing had always seemed to hover in her eyes, and it was gone now. For the first time in all the years Sparhawk had known her, Sephrenia seemed complete and totally happy.

‘Will this go on for long, Sparhawk-Knight?’ Engessa asked politely. ‘Sarsos is close at hand, but…’ He left the suggestion hanging.

‘I’ll talk with them, Atan. I

might

be able to persuade them that they can continue this later.’ Sparhawk walked toward the excited group near the carriage. ‘Atan Engessa just made an interesting suggestion,’ he said to them. ‘It’s a novel idea, of course, but he pointed out that we could probably do all of this inside the walls of Sarsos – since it’s so close anyway.’

‘I see

that

hasn’t changed,’ Sephrenia observed to Ehlana. ‘Does he still make these clumsy attempts at humour every chance he gets?’

‘I’ve been working on that, little mother,’ Ehlana smiled.

‘The question I was really asking was whether or not you ladies would like to ride on into the city, or would you like to have us set up camp for the night.’

‘Spoil-sport,’ Ehlana accused.

‘We really should go on down,’ Sephrenia told them. ‘Vanion’s waiting, and you know how cross he gets when people aren’t punctual.’

‘Vanion?’ Emban exclaimed. ‘I thought he’d be dead by now.’

‘Hardly. He’s quite vigorous, actually.

Very

vigorous at times. He’d have come with me to meet you, but he sprained his ankle yesterday. He’s being terribly brave about it, but it hurts him more than he’s willing to admit.’

Stragen stepped up and effortlessly lifted her up into the carriage. ‘What should we expect in Sarsos, dear sister?’ he asked her in his flawless Styric.

Ehlana gave him a startled look. ‘You’ve been hiding things from me, Milord Stragen. I didn’t know you spoke Styric.’

‘I always meant to mention it to you, your Majesty, but it kept slipping my mind.’

‘I think you’d better be prepared for some surprises, Stragen,’ Sephrenia told him. ‘All of you should.’

‘What sort of surprises?’ Stragen asked. ‘Remember that I’m a thief, Sephrenia, and surprises are very bad for thieves. Our veins tend to come untied when we’re startled.’

‘I think you’d all better discard your preconceptions about Styrics,’ Sephrenia advised. ‘We aren’t obliged to be simple and rustic here in Sarsos, so you’ll find an

altogether different kind of Styric in those streets.’ She seated herself in the carriage and held out her arms to Danae. The little princess climbed up into her lap and kissed her. It seemed very innocuous and perfectly natural, but Sparhawk was privately surprised that they were not surrounded by a halo of blazing light.

Then Sephrenia looked at Emban. ‘Oh, dear,’ she said. ‘I hadn’t really counted on your being here, your Grace. How firmly fixed are your prejudices?’

‘I like

you

, Sephrenia,’ the little fat man replied. ‘I resent the Styrics’ stubborn refusal to accept the true faith, but I’m not really a howling bigot.’

‘Are you open to a suggestion, my friend?’ Oscagne asked.

‘I’ll listen.’

‘I’d recommend that you look upon your visit to Sarsos as a holiday, and put your theology on a shelf someplace. Look all you want, but let the things you don’t like pass without comment. The empire would really appreciate your co-operation in this, Emban. Please don’t stir up the Styrics. They’re a very prickly people with capabilities we don’t entirely understand. Let’s not precipitate avoidable explosions.’

Emban opened his mouth as if to retort, but then his eyes grew troubled, and he apparently decided against it.

Sparhawk conferred briefly with Oscagne and Sephrenia and decided that the bulk of the Church Knights should set up camp with the Peloi outside the city. It was a precaution designed to avert incidents. Engessa sent his Atans to their garrison just north of the city wall, and the party surrounding Ehlana’s carriage entered through an unguarded gate.

‘What’s the trouble, Khalad?’ Sephrenia asked Sparhawk’s squire. The young man was looking around, frowning.

‘It’s really none of my business, Lady Sephrenia,’ he said, ‘but are marble buildings really a good idea this far north? Aren’t they awfully cold in the winter time?’

‘He’s so much like his father,’ she smiled. ‘I think you’ve exposed one of our vanities, Khalad. Actually, the buildings are made of brick. The marble’s just a sheathing to make our city impressive.’

‘Even brick isn’t too good at keeping out the cold, Lady Sephrenia.’

‘It is when you make double walls and fill the space between those walls with a foot of plaster.’

‘That would take a lot of time and effort.’

‘You’d be amazed at the amount of time and effort people will waste for the sake of vanity, Khalad, and we can always cheat a little, if we have to. Our Gods are fond of marble buildings, and we like to make them feel at home.’

‘Wood’s still more practical,’ he said stubbornly.

‘I’m sure it is, Khalad, but it’s so commonplace. We like to be different.’

‘It’s different, all right.’

Sarsos even smelled different. A faint miasma hung over every Elene city in the world, an unpleasant blend of sooty smoke, rotting garbage and the effluvium from poorly-constructed and infrequently drained cesspools. Sarsos, on the other hand, smelled of trees and roses. It was summer, and there were small parks and rose bushes everywhere. Ehlana’s expression grew speculative. With a peculiar flash of insight, Sparhawk foresaw a vast programme of public works looming on the horizon for the capital of Elenia.

The architecture and layout of the city was subtle and highly sophisticated. The streets were broad and, except where the inhabitants had decided otherwise for aesthetic reasons, they were straight. The buildings were all sheathed in marble, and they were fronted by graceful

white pillars. This was most definitely

not

an Elene city.

The citizens looked strangely un-Styric. Their kinsmen to the west all wore robes of lumpy white homespun. The garb was so universal as to be a kind of identifying badge. The Styrics of Sarsos, however, wore silks and linens. White still appeared to be the preferred colour, but there were other hues as well, blue and green and yellow, and not a few garments were a brilliant scarlet. Styric women in the west were very seldom seen, but they were much more in evidence here. They also wore colourful clothing and flowers in their hair.

More than anything, however, there was a marked difference in attitude. The Styrics of the west were timid, sometimes as fearful as deer. They were meek – a meekness designed to soften Elene aggressiveness, but that very attitude quite often inflamed the Elenes all the more. The Styrics of Sarsos, on the other hand, were definitely not meek. They did not keep their eyes lowered or speak in soft, hesitant voices. They were assertive. They argued on street corners. They laughed out loud. They walked along the broad avenues of their city with their heads held high as if they were actually proud to be Styric. The one thing that bespoke the difference more than anything else, however, was the fact that the children played in the parks without any signs of fear.

Emban’s face had grown rigid, and his nostrils were pinched-in with anger. Sparhawk knew exactly why the Patriarch of Ucera was showing so much resentment. Candour compelled him to privately admit that he shared it. All Elenes believed that Styrics were an inferior race, and despite their indoctrination, the Church Knights still shared that belief at the deepest level of their minds. Sparhawk felt the thoughts rising in him unbidden. How dare these puffed-up, loud-

mouthed Styrics have a more beautiful city

than any the

Elenes could construct? How dare they be prosperous? How dare they be happy? How dare they strut through these streets behaving for all the world as if they were every bit as good as Elenes?

Then he saw Danae looking at him sadly, and he pulled his thoughts and unspoken resentments up short. He took hold of those unattractive emotions firmly and looked at them. He didn’t like what he saw very much. So long as Styrics were meek and submissive and lived in misery in rude hovels, he was more than willing to leap to their defence, but when they brazenly looked him squarely in the eye with unbowed heads and challenging expressions, he found himself wanting to teach them lessons.

‘Difficult, isn’t it, Sparhawk?’ Stragen said wryly. ‘My bastardy has always made me feel a certain kinship with the downtrodden and despised. I found the towering humility of our Styric brethren so inspiring that I even went out of my way to learn their language. I’ll admit that the people here set my teeth on edge, though. They all seem so disgustingly self-satisfied.’

‘Stragen, sometimes you’re so civilised you make me sick.’

‘My, aren’t

we

touchy today?’

‘Sorry. I just found something in myself that I don’t like. It’s making me grouchy.’

Stragen sighed. ‘We should probably never look into our own hearts, Sparhawk. I don’t think anybody likes everything he finds there.’

Sparhawk was not the only one having trouble with the City of Sarsos and its inhabitants. Sir Bevier’s face reflected the fact that he was feeling an even greater resentment than the others. His expression was shocked, even outraged.

‘Heard a story once,’ Sir Ulath said to him in that

disarmingly reminiscent fashion that always signalled louder than words that Ulath was about to make a point. That was one of Sir Ulath’s characteristics. He almost never spoke

unless

he was trying to make a point. ‘It seems that there was a Deiran, an Arcian and a Thalesian. It was a long time ago, and they were all speaking in their native dialects. Anyway, they got to arguing about which of their modes of speech was God’s own. They finally agreed to go to Chyrellos and ask the Archprelate to put the question directly to God himself.’

‘And?’ Bevier asked him.

‘Well, sir, everybody knows that God always answers the Archprelate’s questions, so the word finally came back and settled their argument once and for all.’

‘Well?’

‘Well what?’

‘What

is

God’s native dialect?’

‘Why, Thalesian, of course. Everybody knows that, Bevier.’ Ulath was the kind of man who could say that with a perfectly straight face. ‘It only stands to reason, though. God was a Genidian Knight before he decided to take the universe in hand. I’ll bet you didn’t know that, did you?’

Bevier stared at him for a moment, and then began to laugh a bit sheepishly.

Ulath looked at Sparhawk, and one of his eyelids closed in a slow, deliberate wink. Once again Sparhawk felt obliged to reassess his Thalesian friend.

Sephrenia had a house here in Sarsos, and that was another surprise. There had always been a kind of pos-sessionless transience about her. The house was quite large, and it was set apart in a kind of park where tall old trees shaded gently-sloping lawns and gardens and sparkling fountains. Like all the other buildings in Sarsos, Sephrenia’s house was constructed of marble, and it looked very familiar.

‘You cheated, little mother,’ Kalten accused her as he helped her down from the carriage.

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘You imitated the temple of Aphrael on the island we all saw in that dream. Even the colonnade along the front is the same.’

‘I suppose you’re right, dear one, but it’s sort of expected here. All the members of the Council of Styricum boast about their own Gods. It’s expected. Our Gods would feel slighted if we didn’t.’

‘You’re a member of the council here?’ He sounded a bit surprised.

‘Of course. I

am

the high priestess of Aphrael, after all.’

‘It seems a little odd to find somebody from Eosia on the ruling council of a city in Daresia.’