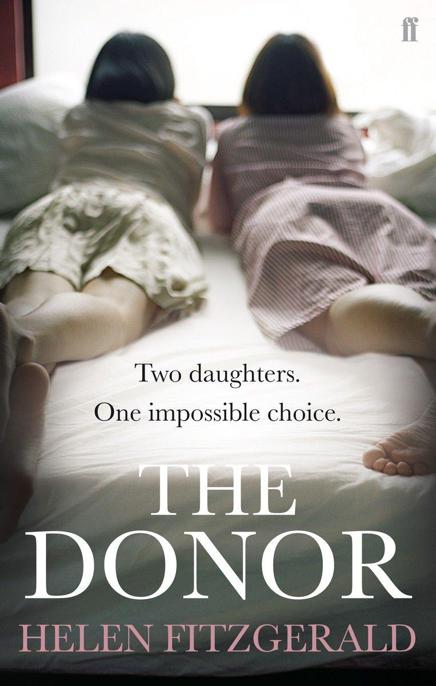

Donor, The

Authors: Helen FitzGerald

HELEN FITZGERALD

FOR MY SIBLINGS:

Mary-Rose, Patrick, Brian, Michael,

Peter, Catherine, Bernadette, Gabrielle, Anthony,

Elizabeth, Angela and Ria (sorry if I’ve forgotten anyone)

Title Page

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

About the Author

By the Same Author

Copyright

It was very good news. Someone had just died.

‘Get to the hospital as fast as you can,’ the doctor said and I asked the driver to get a move on … Oh God, hurry! I’d waited and waited for the call. I’d stared at my hospital-only phone for what seemed like

forever

, wondering what I’d feel like when it finally rang. I’d jumped every time I realised I’d forgotten to charge it, or that I’d left it on the hall table before heading out; every time another phone rang or a nearby siren blared.

I always knew my resurrection would mean

someone

else’s death. So how could I have prayed for it? How could I have stroked my special phone, begging it to ring:

Please, just ring, for me?

How could I have spent every moment waiting for someone to die, probably suddenly, probably horribly?

As the car approached the hospital, I told myself this death was not my fault; this gift not one I could refuse. I imagined the dead man being cut into, a bit of him being taken out, placed in one of those silver padded boxes and rushed away in someone’s hand, like a packed lunch of ham sandwiches.

My breath quickened. My hands trembled. It was happening. It was really happening.

Because someone was dead.

Well, not just

someone …

*

My father.

Sitting under the trickle of an electric shower, Will stopped scrubbing and closed his eyes. He’d clawed at his arms for so long that new blood had now joined the red he’d been trying to wash off. He muttered to himself through the spray … ‘I’ve

done

something. At last.’ He slid down and lay on the cold enamel of the empty bath. He smiled. He had saved his daughters. They could go to the hospital now and reclaim their lives.

All he had to do was wait. The blood was all gone now. He’d wait and while he was waiting he’d think about where it all started.

The Bothy.

Eighteen years ago.

*

There was a girl on stage singing her band’s latest

offering

, ‘Wolf Whistle’. Her voice was deep and unusual, the song an angry anthem which seemed to be aimed at all men. Her black dress was so short that her

panties

were visible. He had a drink in each hand because Si, his best mate, had bought in bulk to avoid queues, and Will couldn’t decide which one to start with. The beer on the right? Or the cider on the left? He liked both equally, but in different ways. He looked at the beer …

Pick me. I’m a bit bitter. I’ve got bite. You won’t forget me.

The girl on stage had blue eyes and black hair as large as her voice. She must have seen Will scrutinising her crotch because as soon as he looked up she touched it and winked at him. He was the kind of guy to get embarrassed when caught ogling crotches. He put his head down, gazed at his feet. Something halfway there was bigger than it had been.

Despite Si’s concerns, the crowd was small. Only about forty people. Will covered his own crotch with the glass of cider so none of them would notice. When he looked up at the stage, she winked at him again. She was older than Will – thirty-five or so – as bright and

other

as passion-fruit pulp. She sang a line directly at him –

Your whistle pet, is the closest you’ll get.

Her head was kind of hanging down a bit, her eyes Diana-esque, looking into his.

He hadn’t taken a sip of either drink. He lifted the cider and contemplated it.

Me! Me! I’m sweet. Easy. You won’t even notice me.

The song was over and before Will knew it he was putting his untouched drinks down on the bar because the girl was heading straight for him.

‘What’s your name?’ she said.

‘Will Marion,’ he answered.

‘You’re pretty. What do you do?’

‘It’s a long story.’

‘Then don’t tell me … Want to come backstage?’

‘Like a groupie?’ he asked.

‘Yes.’

Will was twenty-nine years old. He’d only had sex with two women: Jennifer Gleeson – who’d asked him to please stop poking at her pubic bone and go get some biology lessons, and Rebecca McDonald, who’d chucked him three months before the gig. They’d been together seven years. He wasn’t expecting it. ‘You’re a stoner,’ she said. ‘You do nothing and I’ve come to hate the very sight of you.’

This woman, Cynthia, would eventually be his third. Sober as a bastard, Will found himself sitting on a very high and wobbly wooden stool in a grotty backstage dressing room, listening as she sang the song again, just for him. She lit a joint when she’d finished (the song wasn’t better the second time), drew on it for over three seconds, then asked him if he wanted to kiss her or would he rather she kissed him.

Will was a good man. As a kid he never bullied

anyone

, or cheated in tests, or ran away from home or told his father he was a stuck-up arsehole. Later in life, he never got into trouble with the police or broke a woman’s heart. So he was good, see, but he wasn’t decisive.

‘Does it make a difference?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ she answered.

‘Then you decide,’ Will suggested.

‘You kiss me.’

So he did.

An indecisive man needs a decisive woman.

Cynthia told Will to work hard, because if he worked hard, he was sure to be the next Steven Spielberg. He did for a while, and she brought him strong tea and smiled as he scribbled notes for a screenplay in his office.

Cynthia told Will to follow her guidance. If he did, he would be a champion lover in no time at all. Many hours were spent in bed in the first year or so. Cynthia said Will was a very quick learner. Will said Cynthia’s skin drove him wild with desire.

She told him to take care of her, to cook for her, to massage her back. If he did, she would be the content and normal person she had never managed to be. The meals were regular and delicious, the massages calming and loving.

A while later, she told him to take the job with his father’s holiday letting business. Perhaps hard work wasn’t enough. His writing and directing projects had come to nothing.

She told him she wasn’t hungry so much any more, that regular meals just represented

more

rules, and that perhaps he was using too much baby oil during the massages.

She told him she’d take care of the contraception …

And that the twins should be named Georgie and Kay.

Cynthia told Will to keep an eye on the kids while she went out to the shops.

*

Will was thirty-three when Cynthia went out to the shops. It was a Saturday morning. Georgie, three years old by then, was screaming because she wanted to go with her mum and get a lollipop. Kay was asleep,

oblivious

as usual to the tantrums of her sister. When Kay woke up, they waited by the window to wave when Cynthia walked towards the front door.

If she had walked towards the front door she’d have seen a picture-postcard happy family. Loving partner: smiling. Feisty three-year-old: banging glass. Gorgeous three-year-old: chuckling.

But she didn’t. At 1 p.m. Will phoned her mobile (which she’d left in the house). By 2 p.m. he’d pushed the double buggy to Cynthia’s friend’s house; she lived two streets down and liked the odd snort.

‘Ah, she didn’t come back?’ Janet said. ‘Ah.’

Janet was bohemian, which meant her flat was a pigsty, her hair was all over the place and her expressive

butternut

squash-sized breasts were dangerously

unharnessed

. With her toddler gnawing at the bottom of her T-shirt dress, Janet told him what she knew.

Cynthia was sick and tired of him.

Cynthia never asked to be a mother.

She was trapped.

Using again.

She wanted to be famous!

She’d emptied what there was in the accounts.

Bagged Will’s expensive filming equipment.

And taken off with Heath.

*

Ah, Heath. He and Cynthia were like brother and

sister

– same foster parents as disenfranchised teens, same angry band as young adults, same love of drugs and free expression.

Will first met him about a year after he and Cynthia got together. Fresh out of jail, he arrived on the

doorstep

, drunk and with a bleeding cut on his

cheekbone

. He hugged Cynthia and said, ‘Well, if it isn’t Mrs Marion! It’s been too long.’ He patted Will’s back hard enough to dislodge food, and said, ‘So you’re Mr Cynthia? How ’bout we all have a beer, eh?’

The three of them sat around the kitchen table while Heath described his latest adventure – his celebratory first night of freedom – which involved a baseball bat and five other men. Will laughed nervously. He’d never known anyone so scary in all of his life. If he ran out of beer, would Heath smash his head in with a baseball bat? Was the baseball bat in the large black bin liner he had with him?

‘He’s my brother, really,’ Cynthia told Will

afterwards

. ‘My only family. I know he’s different, from a different world, but can you try to get on, for my sake, please?’

Will tried. When Heath rang the doorbell at three in the morning a month later, huffing from a scuffle, wanting the sofa and the television and a bit of a chat with his best friend in the world, he smiled and said he might get a bit of shut-eye and leave them to it.

When he and Cynthia started the band again,

heading

out all weekend to wow crowds of around fifteen, he smiled and said he was glad she was doing

something

she loved.

He tried to get on with him, but he only ever

managed

to fear him. Heath was a thug. He was volatile. He was dangerous.

And now, his wife had taken off with him.

How could she? Wouldn’t it be like incest, if they were brother and sister really? Wouldn’t she be scared all the time? Worried all the time? If Cynthia wanted to be with this guy, this brute, then who on earth was she? Certainly not the woman he cooked for and massaged, not the one whose soft skin made him wild with desire.

Will’s parents and Si had tried to warn him.

‘Are you sure about this?’ his mum had asked when they moved in together.

‘She’s too … different,’ his dad had said.

‘She’s a junkie nutjob,’ Si had said. ‘What the fuck do you think you’re doin’, man?’

They were all spot on. Cynthia belonged with Heath. Why he ever thought they’d work out in the long term, he’d never know. If he’d been more decisive he’d have said no to her stupid ideas – boring job, premature parenthood. If he was more decisive, he’d have realised that his attraction to her was based on awe and sex. She was like a weird bright outfit bought on holiday. She should never have been worn back home.

But he loved her. She was the artist he wanted to be. She sang in pubs with Heath and her mates, whereas Will – since completing a degree in Visual Arts – had directed nothing except the most basic of dinners. When they met Will was unemployed and living with his parents. The three film projects he’d started at uni had been in development hell ever since. He’d had good ideas, grand plans, but he rarely made it beyond the list-of-things-to-do stage. If he did ever actually write a treatment or a screenplay – and someone else offered an opinion (a writer, a producer, a financier) – he doubted himself, allowed the original idea to change and change, taking on board everyone’s concerns, moving it, ruining it, going round and round in circles.

He was beginning to realise that his entire life was one long, tortuous development hell. Going nowhere. All he really did was watch movies, drink wine, listen to music, and eat crisps like a seventeen-year-old.

During their time together he had done everything to keep Cynthia around him, as if her very presence would inject him with something interesting, because God knows there was nothing interesting about him.

He understood why she went for him to begin with. He was young and allegedly good looking, and he promised he’d make her rich and famous. His initial step would be to produce an amazing music video. In their first year together he made several attempts at shooting and cutting the video, but he never quite finished it. Alcohol-inspired ideas, which he scribbled on scraps of paper as he sat on the sofa bed in his office at night, never quite materialised on film the next day. The Cynthia project ended up in messy piles in his office along with most of the others he’d ever started, until one day, she decided to do it herself. She set up the camera and sang to it. She went out and about with her band-member mates. She edited it at night using his expensive software. She filmed Will, too, to check things were working, she said.

* * *

She didn’t even leave a note.

‘Back soon,’ she’d said, grabbing her patchwork baba bag and skipping out the door. He was sure she was skipping.

Si came around that night. He still lived in Edinburgh, an hour’s drive from Will’s Glasgow house. They’d lost touch for a couple of years while Will changed nappies and tried to please Cynthia. ‘What a bitch!’ Si said. ‘What a fucking bitch.’ He gave Will too much beer, advised him to track her down and kill her and left to go home and sleep for eight hours. Unlike Will, who only managed about two hours’ shut-eye in total because Georgie kept waking up and asking, ‘Where’s Mummy?’

Bloody good question.

*

Why didn’t Will try and find her? Why didn’t he pull out all the stops, get off his backside and beg her to come back? He knew why now. He might even have known then but he dulled the truth with wine and soppy music. The reason was this: Will Marion was a useless lazy idiot fuckwit. He always had been. His father was right. When Will got his report cards each year, his father would say, ‘Is there anything you’re good at, boy?’ When Will’s girlfriends chucked him they both said something like, ‘You’re going nowhere, Will.’ When Will’s film projects evaporated, Si said, ‘What do you expect, mate? You didn’t even try.’

Why didn’t he? Why didn’t he study hard at school, work harder at relationships, work harder at work? The easy answer was that he couldn’t be arsed. The hard answer was that he couldn’t be arsed because he was certain he would fail.

So instead of failing to find her and failing to

persuade

her to come back, Will made excuses. Practical ones like babysitting. His parents wouldn’t help him if he asked them, would they? They were glad to see the back of her. No point asking them to take the kids for a few days while he retraced her steps. They were the kind of grandparents who liked to tell their friends how superior their grandchildren were but had

bugger

all to do with them. They’d babysat once by the time Cynthia left, and only for about an hour. So there was no point, was there? And he didn’t ask Si because he made both kids cry just by entering the room. He didn’t ask Janet, or pay someone, convincing himself that it was the

Why

that stopped him looking for her.

What good would it have done to find her? She had another lover. She was using heroin. And deep inside, helped by the wine Will drank after the kids went to bed, he understood her reasons and admired her for it. She was better than him. She had to leave.

Confirmation of this arrived in the post two weeks after she left. It was a videotape from Cynthia. She’d scribbled on top: ‘I had no choice’. Will made Georgie cry by ripping

Pingu

from the video player, inserting his wife’s tape, and pressing play.