Don't Break the Bank: A Student's Guide to Managing Money (12 page)

Read Don't Break the Bank: A Student's Guide to Managing Money Online

Authors: Peterson's

Tags: #Azizex666

Source:

TheMint.org

Where Does This Money Go?

Congratulations, you are now a taxpayer! Most of the deductions from your paycheck are taxes that go to the government (either federal, state, or local) to fund various programs and services. These include everything from large national programs, like Homeland Security, to local services like pothole repairs.

Depending on how much you earn, you may be able to get some or all of your tax payments back in the form of a refund when you file your taxes at the end of the year. Your parents can help you with this.

Tip:

You should always review your pay stub carefully as soon as you get it. Make sure you are paid for the correct number of hours you worked, and watch for any other mistakes. Should you spot any errors, notify your employer right away.

When you first start working at a job, you will probably fill out a lot of paperwork. One form you’ll no doubt complete is the IRS W-4 form. This is an important form and one that many people find confusing. The W-4 helps your employer figure out how much money to withhold from your paycheck for federal taxes.

On the W-4, you list the number of

withholding allowances

you want to claim. This is an IRS term that basically means how much money you want to go to the IRS towards your taxes. The more allowances you claim, the less money is withheld for taxes. If you claim zero allowances, your employer will hold the maximum amount from your check.

Why is this so important? If your employer doesn’t withhold enough money from your paycheck to cover what you owe in taxes, you will end up owing the government money at the end of the year. On the other hand, if too much is withheld, you will get a tax refund. Most people think that’s a good thing—but it really means that you’ve been letting the government use some of your money all year, interest-free.

The IRS has a withholding allowance calculator on its Web site to help you determine what figure to enter on this line. But here is some basic advice from Bruce D. Kowal, CPA, of

www.KowalTaxClinic.com

. “Using 2010 tax rates, a 16-year-old student can earn up to $11,100 with no federal income tax liability. This is because of the Making Work Pay credit. However, this individual still has to pay social security taxes, which are automatically withheld—no choice here. So, if the student is earning less than $12,000, he or she can fill out the W-4 as Single and Zero allowances.”

Here is what the W-4 form looks like:

Source: IRS

The Most Common Payroll Deductions

[Source: Roger A. Smith, CPP;

www.payrollprof.com

]

Federal Income Tax

Federal Income Tax is a tax that employers are required to withhold from their employees’ pay. It is detailed in the Internal Revenue Code and regulations issued by the Department of Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service. Money collected is used to fund many national programs, such as defense, law enforcement, and general running of the county. The amount withheld is applied to an employee’s annual tax liability itemized on the yearly tax return.

State/Local Income Tax

Similarly, states and many local taxing authorities also require employers to withhold income tax from their employees. These dollars are used to fund state and local programs, such as road maintenance, local law enforcement, and other state and local expenses.

Social Security Tax

Social Security Tax, also called

FICA

, is used to pay out federally provided retirement benefits to citizens who are at least 62 years old. It is also used to pay out benefits to disabled citizens who are unable to work. Social Security Tax is applied to the first $106,000 earned in 2011.

Medicare tax

Medicare Tax is used to pay out federally provided health-care benefits for the citizens over age 65.

Insurance Deductions

Currently, many employers offer employees the option to enroll themselves and their family members in a group health plan and/or group life insurance plans. These plans can be funded entirely by the employer (very rare), entirely by the employee, or by both the employer and employee. Depending on how the plan is constructed, employee dollars used to pay their portion of the health plan can be pretax contributions. Pretax contributions are dollars that are NOT added into the employee’s taxable earnings used to calculate taxes. In the previous example of John Q. Employee, the insurance deduction was a non-pretax (or post-tax) contribution.

Retirement Saving Plan Deductions

Many employers also give employees the option to participate in various types of retirement savings plans. Like the insurance plans mentioned above, these plans can be funded entirely by the employer (e.g., pension plans), entirely by the employee, or by both the employer and employee. Depending upon how these plans are constructed, the employees’ dollars used to pay their portion of the contribution can be pretax contributions (e.g., 401K plan deduction). However, employee pretax contributions are used when calculating Social Security Medicare Taxes and, if you happen to live in Pennsylvania, state tax as well.

Flex Spending Deduction

As one of the many tax breaks given to U.S. citizens, employers can allow their employees to establish tax-free savings accounts. These are called Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs), and there are two types: One type can be used to pay for medical expenses not covered by insurance, like co-payments for doctor’s visit, prescription eyeglasses, or the rental of medical equipment, and the other type is used to pay for dependent care.

Health Savings Account Deduction

Health savings accounts (HSAs) are a relatively new thing. They are a way for you to establish a fund to pay for medical expenses. The money you put into your HSA is tax-exempt, meaning it is taken out of your paycheck before taxes, so you don’t pay taxes on that income. You can only participate in an HSA if you have a high-deductible insurance plan and no other health coverage. The money you put into an HSA can accumulate and “roll over” from year to year.

Charity Deduction

As a service to the employee and the community, many employers allow their employees to contribute directly to one or more charitable organizations.

Part III

Banking 101

When you think about banks, you probably imagine a very simple process: you put your money into the bank and/or you take it out. The banking process is a lot more complicated than that, though. There are different types of banking institutions, but they do have some things in common, such as the use of interest and the need to follow federal rules and banking regulations. It’s important to understand the basics of banking so that you can be a smart consumer, compare services, and watch out for fees.

In addition, you do lots of things online, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that you can do your banking, pay your bills, and conduct other financial transactions via your computer. Online banking and bill paying is easy and convenient, but there are important issues (such as security concerns) that you need to know about—and we’ll give you the essential info you need.

Chapter 5

Making Cents Out of Banking

You’ve probably heard stories about how people in the old days used to keep their money in their mattress. Well, people realized that’s not really a good idea for a bunch of reasons (burglaries, fire, bed bugs, you name it). So now most people keep their money in a bank. Banks also offer other services that can make your life easier, such as providing a debit card, giving loans, and helping you save for a goal or emergency fund.

How Banks Work

When you give a bank some of your money to hold on to (called a

deposit

), the bank keeps your money safe, and it also gives you a little extra for your trouble. This is called

interest.

The bank then uses the money from deposits to give loans to other people. In this case, the bank

charges

interest. So it’s basically like a constant revolving door: the bank takes money in, while at the same time it is lending money out.

Now this is Interesting: Understanding Interest Rates

Interest

is what you earn by keeping your money in a bank. It is basically the fee the bank pays you for letting it keep (and use) your money. Interest works on a percentage basis. So, say, if the bank offers 4% interest, it will pay you 4% of whatever your balance is. So, if you deposit $100, you will earn 4 cents in interest after a certain period of time.

A bank is a business. In fact, it invests your money so that it can make more money of its own. In return, the bank pays you interest for the use of your cash, which is not much right now. The bank earns income by collecting money from businesses and people who want to keep their money in the bank. The bank lends this money to others and charges them interest for their loans.

~

Ornella Grosz, Financial Literacy Advocate and Author of

“Moneylicious: A Financial Clue for Generation Y”

The interest rate a bank offers varies depending on the economy. You can always ask an employee at your bank what the current interest rate is.

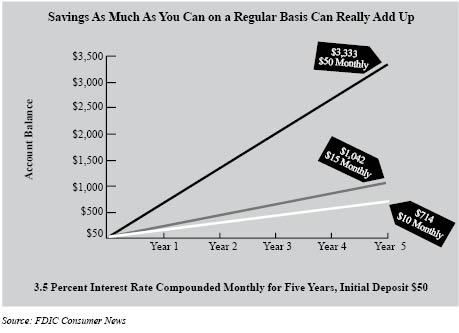

You might be amazed at how quickly your money can grow thanks to interest. This is partly due to a sort of magical thing called “compound interest.” Here’s what that means: At the end of the first month, your account earns interest based on what you started out with (your initial deposit). You will then have a new balance—your deposit plus the added interest. Now, the next month, you will earn interest on that current amount. In other words, you will earn interest on your interest. (Got that?) For example, if you have a dollar and you get 4 cents interest, the bank will use $1.04 as the starting amount next time when calculating your interest.

For a hands-on look at how interest compounds, check out the Compounding Calculator at TheMint.org, developed by the Northwestern Mutual Foundation with the National Council on Economic Education (NCEE). TheMint.org is endorsed by the American Library Association. Visit: http://themint.org/kids/compounding-calculator.html.

72 Reasons to Love Banking

“It’s never too early to start saving. There is this thing called compound interest that will work wonders if you let it. Let’s say you put aside just $166 each month for eight years starting at the age of 19, for a total of $16,000. If you let it grow in an investment fund that averages a 12% interest rate, you’ll have $2,288,966 when you graduate. $16,000 turned into $2,288,966! I know $166 a month is a lot for a college student, but even if you can’t save that, $50 is better than nothing.