Dorset Murders (22 page)

This latter theory was somewhat strengthened by the reported sighting of an attractive young woman, dressed in a white hooded coat, near the kennels at around the time of the shooting. Nobody could provide any logical explanation why a woman should have been walking alone on the isolated country lane so early in the morning.

Could robbery have been a motive for someone to shoot Welham? He had 10

s

in his wallet when his body was found and there were nine pounds locked in a drawer in the office. However, his employer, Frampton, believed that Welham should have had at least £10 on his person. A horse rider came forward to say that, on the morning of the murder, while riding near the kennels, he had been approached by a middle-aged man who, after asking the time, had become aggressive and demanded to be given some money. Later in the day, an attempt was made to snatch money from the till of a public house at nearby Wimborne. The would-be raider, again described as a middle-aged man, had fled empty handed after being confronted by the pub landlady.

The inquest into Welham's death was reconvened and adjourned on 10 and 23 October, yet the police seemed no nearer to finding the identity of his killer. Whoever had committed the murder had managed to choose a window of approximately ten minutes while Deamen was out searching for the missing spaniel, leaving the victim alone in his office. The killer had somehow managed to avoid disturbing the forty or so dogs on the premises since no unusual barking had been heard. He â or she â had removed the victim's shotgun from its place in the cupboard near the desk and loaded it, apparently without Welham noticing. Then, having fired the gun, the killer staged a suicide by placing the weapon under Welham's body.

Welham was known to be extremely careful with firearms and it was unthinkable that he would have kept a loaded gun in his office unless he was intending to use it. Harold Hathaway had cleaned the gun only hours before the murder and replaced it unloaded in the cupboard. Welham had no known enemies and did not appear to be in the frame of mind to commit suicide.

Eventually, on 27 October and with no new evidence, the coroner's jury returned a verdict of âwilful murder by person or persons unknown' and the coroner formally closed the inquest, making a final appeal to the public via the press. âI have felt that someone, somewhere â I don't say among the witnesses â knows something but has said nothing. If there be any such person, be it witness or one who has never given any opinion, they are standing in a very precarious position if they do not make known what they know'.

With no further leads to follow, the officers returned to Scotland Yard and life carried on as normal in the hamlet of Tarrant Keynston. It was an especially busy time for young Fred Deamen. On 30 October, he appeared before magistrates at Wimborne, charged with the theft of a camera from Ethelbert Frampton and a pair of gloves from the Coverdale Kennels.

Deamen denied both charges, maintaining that he had bought the camera from a man he had met on his way home from work and that the gloves had been discarded by their owner and left lying around at the kennels dirty and covered in mildew. He had taken them in the belief that they were no longer wanted. In the event, both charges against him were dismissed but, just a day or two later, Deamen had an accident while riding his motorcycle and was rushed to hospital semi-conscious.

It was while Deamen was recovering from his injuries in hospital that the investigations into the murder of his boss took an unexpected turn, bringing police rushing back to Dorset from Scotland Yard.

After first consulting with Ethelbert Frampton, Tom Hathaway approached the local police saying that he wished to amend his statement made after the discovery of the body. In an interview with Chief Inspector Hambrook, Hathaway now revealed that, on entering Welham's office, he had noticed a hazel stick and a piece of string lying near the body. Thinking to spare Welham's family the ordeal of discovering that he had committed suicide, he had surreptitiously slipped the 2ft 9in length of string into his pocket and removed the hazel stick to which it was attached to a corner of the office.

Hathaway had assumed that a verdict of accidental death would be returned at the inquest. Now, with a verdict of murder, he was afraid that someone might be arrested for a crime that hadn't actually been committed. Although he undoubtedly meant well, Hathaway's actions had muddied the waters of the investigation and may have allowed Welham's killer to walk free.

Hathaway's revelations prompted a new round of experiments with Welham's gun, this time making use of the piece of string found at the scene, which Hathaway had kept and handed over to the police. However, rather than proving that Welham had committed suicide, the string finally and conclusively confirmed that his death had been murder, since it was far too short to have been used to fire the weapon given the distance from which it had been discharged. Even PC Head, who until this point had been unshakeable in his belief that Welham had committed suicide, was forced to concede that he had been wrong. All that the string and hazel stick showed was that the killer had been even more inventive in his or her attempts to make the killing look like suicide, indicating that the murder had been premeditated rather than the result of a sudden impulse in the heat of passion.

The murder of Edward Welham remains unsolved to this day.

âI DID IT DELIBERATELY AND I'D DO IT AGAIN'

â

D

o you know that you have a lovely face?' asked the young woman. The recipient of this compliment was astounded.

âGreat Scott! Have I?' he exclaimed. âI'm going home right now to have a look at it. I never thought it worth looking at yet.'

âI'm not joking', insisted the woman. âYou have almost the kindest face I ever saw.'

Little did either the man or the woman know that these flattering words would eventually lead to a marriage, extra-marital affairs, scandal and, ultimately, murder.

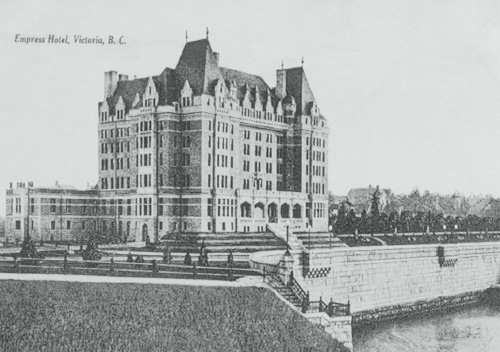

The young woman was Alma Victoria Pakenham, a Canadian concert pianist; the man was Francis Mawson Rattenbury, an elderly British architect working in Canada. The couple first met in 1922 after a piano recital given by Alma at a hotel in British Columbia. Relaxing in the hotel lounge with a friend after her performance, Alma heard the rousing strains of âFor He's a Jolly Good Fellow' coming from another part of the hotel and casually remarked that the singers seemed really sincere in their sentiments. Curiosity drew her to investigate the celebrations more closely and she soon discovered that the object of the adulation was Rattenbury, famed for his innovative design of the Canadian parliament buildings, the Law Courts in Vancouver and the Empress Hotel in Victoria. Alma was impressed by his good looks and self-confidence and, when the two were eventually introduced, Rattenbury found himself equally smitten by the vivacious and mercurial Alma.

The Empress Hotel, 1909

.

Although then only twenty-nine years old, Alma had already led a full and interesting life. Aged nineteen, she had married for the first time to a man from Ulster, with whom she had moved to England. Tragically, he had died during the First World War in the Battle of the Somme and, as soon as Alma heard of his death, she joined a Scottish ambulance unit, working behind enemy lines in France. Such was her bravery that she was awarded the Croix de Guerre Medal, with Star and Palm.

When the war ended, she married again, this time to a captain, and the couple moved to America. The marriage broke up after the birth of a son, Christopher, and Alma and her child moved back to Canada to live with her aunt in Victoria.

Now, it seemed, she had another suitor. Having made a point of attending one of her piano recitals, Rattenbury met Alma again by chance shortly afterwards at a dance and, by the end of the evening the couple had fallen in love.

They met at a time when things were not going well for Francis Rattenbury. The fifty-five-year-old man was feeling his age. He had lost interest in his work, complained of several physical afflictions, and was, to the concern of his friends, beginning to look old and unwell. He and his wife of more than twenty years were drifting apart and he was depressed and lethargic. Attracting the attentions of Alma, a woman thirty years his junior, must have acted as a real tonic.

By 1925, Rattenbury's wife had left him, citing her husband's affair with Alma as grounds for divorce. Alma, too, had arranged a divorce from her estranged husband and she and Rattenbury married and moved into his house at Oak Bay with Christopher, who was then three years old. However, their May to December marriage was not well received in Canadian society and eventually Francis moved his wife and stepson back to England where they could make a fresh start.

Manor Road, Bournemouth, 1906

.

The family settled into the Villa Madeira on Manor Road, Bournemouth, from where Alma embraced a new career as a songwriter, writing under the pseudonym âLozanne'. She was quite successful in her new venture and several of her compositions were recorded and played on BBC radio.

In due course, Alma gave birth to the couple's son, John, and subsequently fell ill with tuberculosis. In the meantime, Francis once again began to feel his advancing years. Alma was quite extravagant and, having now retired, Francis worried about money. He was also finding it somewhat of a strain being married to a much younger woman. He and Alma had not shared a bed since John's birth six years previously, and it was almost certain that the still young and highly sexed Alma had taken lovers to compensate for her husband's deficiencies in the bedroom.

By 1935, Rattenbury had fallen into another of his frequent bouts of depression and, on Sunday 24 March, Alma found herself struggling to think of ways to lift his near-suicidal mood. It was a lovely day and Bournemouth was bathed in warm spring sunshine, so she impulsively decided to erect an awning in the garden so that he could sit outside. However, she was unable to find a mallet with which to hammer the pegs into the ground. Stoner, the couple's chauffeur/handyman, mentioned that his grandparents owned one and Alma sent him off to borrow it. While waiting for his return, as a diversion for Francis, she arranged a trip to a nearby kennels to see a litter of puppies that her dog had just borne, but any elevation in her husband's state of mind was all too brief and by tea time that afternoon, he was back to being morose and feeling hopelessly depressed. Over tea, he insisted on reading aloud passages from a book,

Stay of Execution

by Eliot Crawshay-Williams.