Dorset Murders (9 page)

Stressing that the charge against Emma Pitt was a capital charge, Collins implored the jury to think carefully before reaching their decision and to give her the benefit of any doubt that existed in their minds. They should remember that the life of a young girl was in their hands. Throughout Collins's address Emma Pitt sobbed piteously, her gaze fixed steadfastly on the jurors, as it had been throughout the trial.

After the defence counsel's speech, Mr Justice Lush then summed up the case for the jury. The crux of the matter, he told them, was whether or not the child had ever been an inhabitant of this world. If it had had a separate existence and its life had been extinguished as a result of an act by its mother, then the jury should find the accused guilty of wilful murder. Otherwise there was not the slightest doubt that Emma Pitt was guilty of the lesser offence of concealment of birth

The jury retired for only ten minutes before returning with a verdict of âNot Guilty' of murder, but âGuilty' of concealing the birth of a baby. Mr Justice Lush then addressed Emma, telling her that in his opinion this was one of the worst cases of concealment that had come before him. Her conduct during the day on which she was in labour, coupled with her constant denials of her situation to Mrs Parsons, proved conclusively what was her intention, at least with regard to concealment of the birth. For that reason he proposed to give her the maximum sentence allowed him by the law. Emma Pitt, whose face had visibly brightened at the jury's verdict of âNot Guilty', once again burst into noisy sobs as she was sentenced to two years imprisonment with hard labour. She was escorted from the dock to be taken to prison, moaning and crying hysterically.

âI TRIED TO SETTLE ONE LAST LEAVE AND I HAVE SUCCEEDED THIS TIME'

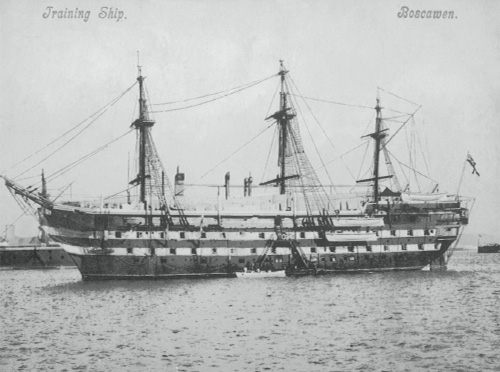

T

he naval training ship HMS

Boscawen

first arrived in Portland in 1862, replacing HMS

Britannia,

which then moved from Portland to Dartmouth to become the forerunner of the Royal Naval College. The original

Boscawen

was replaced in 1873 by HMS

Trafalgar,

which subsequently adopted the name

Boscawen

and remained in Portland until 1906, when she was sold.

Life on a naval training ship in the nineteenth century was not easy for the boys on board, being taught the many and varied tasks they would have to do as men at sea. They learned the rudiments of reading and writing, along with how to set rigging, use rifles, clean and maintain the ship, scrub and wash hammocks and make and mend clothes. They also took part in a punishing schedule of physical exercises and gymnastics. Fire being a great danger on a wooden ship at sea, the boys formed a fire brigade which, in emergencies, could be called on to assist with fires on land. On Sundays, every boy was expected to attend divine service. Discipline on the ship was harsh and in 1866 it is recorded that two boys each received twenty-four lashes from the birch.

By 1891 there were 549 boys on board the

Boscawen,

most aged between twelve and seventeen years old, with each boy receiving weekly pocket money of around 3

d

. As the boys were often prevented from leaving the ship for long periods, due to bad weather or an infectious illness, for which the entire ship was quarantined, life on

Boscawen

could be confining and claustrophobic.

The

Boscawen

training ship, 1905

.

On Sunday 15 November 1891, after attending the religious services, three of the

Boscawen

boys, William Groom, John Wise and Lawrence Salter, obtained permission to go ashore. Together they walked along the top of the cliffs at Portland towards Bow and Arrow Castle, enjoying a rare chance to stretch their legs, chatting and picking blackberries as they went.

William Groom was about thirty yards ahead of the other two, half listening to their conversation about the Shambles lightship, a vessel that warned other ships about the treacherous Shambles sandbar between Weymouth and Portland. Suddenly, what Groom later described as a âgroan' interrupted the talking, and then the conversation abruptly ceased altogether. Turning round to see what had happened, Groom saw John Wise perched precariously on the edge of the 100ft-high cliffs on his hands and knees, peering over the top and laughing loudly. Groom rushed to see what was going on and, as he looked over the cliff, he spotted âa bundle of blue' at the bottom and realised that it was Lawrence Salter.

Children playing in the gardens of the nearby prison cottages had seen Salter fall and raised the alarm. A party of rescuers descended the cliffs, finding Salter still alive but terribly injured. He was brought carefully to the top and taken to the prison infirmary, where he died half an hour later.

Groom asked Wise if he had pushed Salter, but Wise made no reply, and just continued to laugh maniacally, so much so that his legs would no longer support him and he fell to the ground. By now, all the frightened Groom could think of was to get Wise back to the

Boscawen

. He seized Wise's hands, pulled him upright and began to walk him towards the ship. However, on their way back they met one of the ship's officers, Petty Officer First-Class Benjamin Stuckey, and, to his relief, Groom was able to hand Wise over into his charge, after telling the officer that he wished to report Wise because he believed that he had pushed Salter over the cliff. Wise immediately confessed to Stuckey that he had indeed done exactly that â he had deliberately pushed Salter over the cliff in order to get hanged.

Bow and Arrow Castle, Portland, 1917

.

Doubting that Wise could be in his right mind, Stuckey asked the boy if there was anything the matter with him, to which Wise replied that he was subject to âfits of frenzy' and that he must have killed Salter in one of those fits.

Back on board the

Boscawen,

Wise repeated this statement to Lieutenant Andrew Stafford Mills, saying that he had gone ashore with the sole intention of killing somebody. âI tried to settle one last leave and I have succeeded this time', he cheerfully told Mills, continuing to smile and laugh all the while he was being questioned.

An inquest was opened into the death of Lawrence Salter on 17 November, at the Grove Inn, Portland, before Coroner Sir Richard Howard. Wise smiled throughout, even as the coroner's jury recorded a verdict of wilful murder against him. At this, he was arrested and remanded in Dorchester Prison. Shortly afterwards he was brought before Mr Justice Cave at the Dorset Assizes, but the judge was not prepared to hear the case since the alleged murder had happened less than a week before and Wise had not yet been before magistrates. Describing Wise as a poor, friendless boy, Cave warned against pressing on with the case too hastily. In fairness, he said, Wise should be permitted to have witnesses for his defence and, since there were questions about his sanity, he also deserved the benefit of medical opinion.

John Wise duly appeared before magistrates at Dorchester on 11 December 1891. Mr Howard Bowen prosecuted the case and Wise was not defended. It was noted that he was in the hands of a medical expert who would give evidence at âthe proper time'. Wise was committed for trial at the next Assizes.

By the time the trial opened on 7 March 1892, before Mr Justice Wills at Dorchester, extensive investigations had been made into both his medical history and his current state of mind. Mr M.W. McKellar and Mr Evelyn Cecil prosecuted the case and Wise had by now been appointed a defence counsel, Mr A. Cardew.

The court heard accounts of the events of the day of the murder, followed by evidence from the master-at-arms of the

Boscawen,

Robert Franklin.

Franklin told the court that Salter, a native of West Ealing, London, had celebrated his sixteenth birthday the day before his death. He had joined the

Boscawen

on 16 September 1891 and was âwell conducted', as indeed was Wise.

Wise was sixteen-and-a-half years old at the time of Salter's death and had seven months service. During that time he had tried to commit suicide by swallowing oxalic acid. On 23 July 1891, he had boasted to his crewmates that, before joining the ship, he had strangled a young boy at Croydon and buried him behind the Roman Catholic school. When it was suggested that he was delusional, he had assured people that he wished he could think so, but sadly he knew it to be true. It was never established whether Wise's story was actually true or merely a figment of his fevered imagination. What was established, however, was that Wise was a very troubled young man.

Witnesses described him as being âeccentric' ever since he was a child of eight years old, and his father and several other relatives had died in lunatic asylums. Although he had now changed his account of the events surrounding the death of Salter to say that the young sailor's death had been an accident, Wise had assured everyone prior to his trial that he had no personal grudge against his victim but had just seized the opportunity to kill him. There had been no scuffling or fighting, just one swift push. Wise had also said that he did not dislike being in the Navy but that he would just as soon be out of this world that in it.

The jury retired only briefly before returning with their verdict, finding John Wise guilty of the wilful murder of Lawrence Salter but stating that he was insane at the time of the killing. Ironically, for a boy who, by his own account, had committed murder specifically so that he might be hanged, Mr Justice Wills directed that Wise should be detained as a criminal lunatic in Dorchester Prison âuntil her Majesty's pleasure should be known.'

âTHIS IS ALL THROUGH MEN GOING TO MY HOUSE WHILE I'M AWAY'