Down & Dirty (5 page)

Authors: Jake Tapper

At around 6

P.M

. in Tallahassee, Willie Whiting, Jr., fifty, a pastor in the House of Prayer Church, goes with his wife, son, and daughter

to St. John’s United Methodist Church to vote. But Whiting’s name isn’t on the voter rolls.

“You have been purged from our system,” he’s told by one of the white poll workers.

What? That can’t be true, he says. Double-check. The poll worker calls the Leon County elections office. The database has

Whiting listed as a convicted felon.

This shocks Whiting. But unlike most who get caught in a similar situation, Whiting isn’t going to walk away, scratching his

head. “Do I need to call my lawyer?” he asks. Eventually the mistake is cleared up, and Whiting is allowed to vote.

In January of 2000, protesting Jeb’s executive order repealing affirmative-action programs for state contracts and university

admissions, African-American protesters, led by Sen. Kendrick Meek, D-Miami, and Rep. Tony Hill, D-Jacksonville, staged a

twenty-five-hour sit-in in the office of Lt.

Gov. Frank Brogan. Jeb instructed aides to “kick their asses out.” (Jeb later claimed that he had been talking about reporters.)

Pastor Whiting cannot escape the feeling that somehow, in some way, Jeb and others are today just trying to kick his ass out—of

the voting rolls.

Other problems voters have today are less conspiratorial in nature. But they do, for whatever reason, seem to impact black

voters more so than whites.

Quiounia Williams is eighteen. It’s her first election, and she’s excited. She enters the voting booth at First Timothy Baptist

Church, on Biscayne Road in Jacksonville, and puts the card inside the slot. But she’s never done this before, and no one’s

shown her how to do it, and for some reason the card won’t go down. It doesn’t sit still. Every time she punches a hole, the card

moves.

She leaves the booth.

“I couldn’t put the card all the way down,” she tells a poll worker.

“Well,” says the worker, “what actually happened?”

“When I pushed down, every time I got ready to punch a hole, it would move again.”

“Don’t worry about it, baby,” the poll worker, an African-American woman, says, handing her an “I voted!” sticker, telling

her to put the card in the box.

The elections office in Duval County, surrounding Jacksonville, is suffering its own distinct chaos. Despite having decided

not to use Choice-Point’s scrub list, Duval County is having some serious problems, particularly in its predominantly African-American

precincts. Just last weekend, Stafford made sure that 170,000 copies of a sample ballot were inserted into the Sunday editions

of the

Florida Times-Union.

“Step 4 Vote all pages,” it read. But on the Duval ballot, the ten presidential candidates are spread over two pages. Stafford

realized that the sample ballot’s instructions were incorrect and could result in overvotes disqualifying the ballot. So today

the official ballot has different instructions. “Step 4 Vote appropriate pages,” it reads.

Ernest Lewis, for one, is confused. It’s his first time voting. Whether it’s because he remembers the instructions from the

sample ballot, or whether it’s because he’s new at this and he just figured you vote on every page, Lewis votes on both presidential

pages and voids his ballot in the process. More than twenty thousand voters in Duval County will do this today.

Some Florida counties have systems in place that notify voters immediately

if their ballot is invalid, but only 26 percent of black voters live in these counties as opposed to 34 percent of white voters.

That means by sheer numbers white voters have an advantage.

5

In the cotton belt’s Gadsden County on the Georgia line, union officials hustled all June to register two thousand African-American

voters, many of them seniors who had never voted before. But today in Gadsden polling booths, many seem to be making up for

lost opportunities by picking more than one candidate for president. Some are voting for all ten presidential candidates,

then penning Gore’s name on the write-in line. The ballot directions don’t exactly help.“Vote for ONE,” it says above the

race for Senate. “Vote for Group,” it says above the presidential contest.

From the Ochlockonee River to the Apalachicola, more than 2,000 of the 16,812 ballots cast in Gadsden today—two-thirds of

which are going to Gore—will be thrown out. It’s a full 12.33 percent of all ballots cast, the highest percentage in the state.

6

It’s just another uncomfortable superlative for Gadsden—the state’s third-poorest, and only majority-black, county, the only

county in Florida that went for Walter Mondale over President Ronald Reagan in 1984. Here 94 percent of the students at Chattahoochee High

School read below the minimum standard, the county’s schools rank last in the state in reading for fourth, eighth, and tenth

grades, and the school district’s graduation rate—46 percent—is the lowest in Florida.

The pattern is not unique to Gadsden, however. In Miami-Dade County, predominantly black precincts will register an undervote

rate of 10 percent, while areas with few blacks have an undervote rate of 3 percent.

7

Some black neighborhoods in largely black Liberty City and Overtown will register overvote rates of 10 percent, while the

countywide rate will be just 2.7 percent.

8

Undervotes and overvotes will result in 23 percent of the ballots cast—that’s almost one out of every four ballots—by voters

in largely black Palm Beach County areas like Belle Glade, Pahokee, and South Bay being chucked.

9

By noon in Palm Beach County, WPEC-TV is reporting the story of the butterfly ballot, explaining the problem a hell of a lot

better than the Democrats are. Joan Joseph, a Gore coordinator for the north end of the county, instructs her phone-bank supervisor

to urge voters not only to hit the polls but to be wary of the ballot’s confusing design.

They’re getting other weird reports, too. In precinct 162-G, the almost entirely Jewish retirement community called Lakes

of Delray, Pat Buchanan— who has defended accused Nazis, called Hitler “a great man,” argued that the

United States fought the wrong side in World War II, and accused Holocaust survivors of having delusions of martyrdom—is racking

up surprising support.

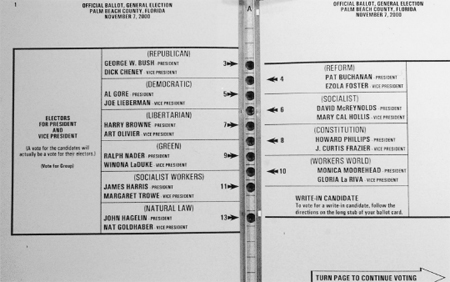

Palm Beach County’s infamous butterfly ballot

Sylvia Robb, wife of Lakes of Delray community president Arthur Robb, is just one of forty-seven voters who punches hole no.

2, thinking it’s for Gore. By the end of the day, no precinct in Palm Beach County will show more votes for Buchanan than

this one.

At 2:57

P.M

., Brochin faxes his letter to LePore again, since he never heard from her the first time.

By 3

P.M

. in Nashville, Whouley decides to switch the phone-script on the paid phone bank calls. Their telemarketing company, TeleQuest,

is called in Texas. The Dems want them to make seventy-four thousand calls in Palm Beach. TeleQuest says they can’t get anywhere

near that number, but the company does make a change. “Some voters have encountered a problem today with punch-card ballots

in Palm Beach County,” the new TeleQuest script reads. “These voters have said that they believe that they accidentally punched

the wrong hole for the incorrect candidate.” To voters who had yet to vote, instructions were given: “punch number 5 for Gore-Lieberman,”

and “do not punch any other number, as you might end up voting for someone else by mistake.

“If you have already voted and think you may have punched the wrong hole for the incorrect candidate, you should return to

the polls and request that the election officials write down your name so that this problem can be fixed.”

Around that time in Palm Beach, the butterfly-ballot cacophony gets cranked up when outspoken Gore-backing talk-radio host

Randi Rhodes tells listeners to WJNO-radio—1290 on your

A.M

. dial—that she had the same problem.

“I got scared I voted for Pat Buchanan,” she says on the air. “I almost said, I think I voted for a Nazi.’ When you vote

for something as important as leader of the free world, I think there should be spaces between the names. We have a lot of

people with my problem, who are going to vote today and didn’t bring their little magnifiers from the Walgreens. They’re not

going to be able to decide that there’s Al Gore on this side and Pat Buchanan on the other side….I had to check three times

to make sure I didn’t vote for a Fascist.”

In retirement condos from Jupiter to Boca Raton, Rhodes’s fans start wondering if they voted correctly.

Many of these seniors are deeply upset. Harold Blue, eighty-seven, enlisted in the cavalry right after Pearl Harbor, landing

in Normandy at D day plus two, remaining in Europe long enough to carry out the cease-fire orders at the end of war, establishing

contact with the Russians. Blue and his wife are legally blind, so at the polling station in a Greenacres public school, he

requests help.

“Number one is Republican, number two is Democrat,” the poll worker advises him. Later, Blue will realize that he punched

the wrong hole. He fought for democratic principles in France, he thinks. But this sure as hell wasn’t a democratic election.

At the elections office, Democratic officeholders like state representative Lois Frankel, state senator Ron Klein, and U.S.

representative Robert Wexler come in and start complaining about the “widespread problem” of the butterfly ballot.

LePore has a real sick feeling in her stomach.“Oh, shit,” she finally thinks.

Calls are coming in from people complaining because they had a problem voting. Poll workers and voters are calling and complaining

that the phones have been busy, because of all the other calls. Harangued by the Democratic officials, LePore finally agrees

to write an advisory about the ballot, though she tells the Democrats that she doesn’t have the support staff to get it to

every precinct, that they’ll have to distribute it. They print out 531 copies:

ATTENTION ALL POLL WORKERS. PLEASE REMIND ALL VOTERS COMING IN THAT THEY ARE TO VOTE ONLY FOR ONE (1) PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE

AND THAT THEY ARE TO PUNCH THE HOLE NEXT TO THE ARROW NEXT TO THE NUMBER NEXT TO THE CANDIDATE THAT THEY WISH TO VOTE FOR.

At around 4

P.M

., Judge Charles Burton—chairman of the Palm Beach County canvassing board—sits in the conference room with LePore and the

third member of the board, Democratic county commissioner Carol Roberts.

An elections office employee brings Burton over a ballot.

“Vote for Gore,” she instructs him. Burton had voted the week before, via absentee ballot.

Burton looks at the ballot, sees the clear arrow from the Gore-Lieberman ticket to the third hole, punches the hole,

bang.

“What’s the problem?” he asks.

“Well, people are getting confused,” she says.

“I don’t really see it,” says Burton, a low-key guy. “But, well, OK.”

Roberts, a strong partisan Democrat, says, “You know they’re starting to say this ballot was illegal. You may need to get

your own lawyer,” she advises LePore.