Drama (2 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

A Curious Life

T

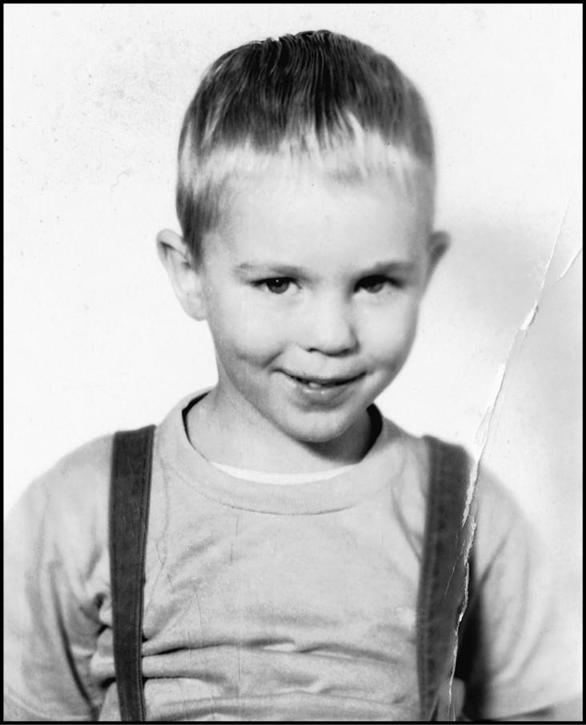

he first time I acted was before I even remember. At age two, I was a street urchin in a mythical Asian kingdom in a stage version of “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” It was 1947, and the show was performed in a Victorian Gothic opera house, long since demolished, in Yellow Springs, Ohio. A black-and-white photograph from that production shows me at the edge of a crowd of brightly costumed grown-up actors. Standing nearby is my sister Robin. She is four, two years older than I, and also a street urchin. We are both dressed in little kimonos with pointy straw hats, and someone has drawn dark diagonal eyebrows above our eyes, rendering us vaguely Japanese. I am clearly oblivious, a faun in the headlights. I stand knee-high next to a large man in a white shift and a pillbox hat who appears to have a role not much bigger than mine. He reaches down to hold my hand. He is clearly in charge of me, lest I wander off into the wings. There is very little in the photograph to suggest that, at age two, I have a future in the theater.

But I do. Later that season, in the same old opera house, I was already back onstage. I played one of Nora’s children in

A Doll’s House

by Henrik Ibsen. I don’t remember this performance either (and there’s no photographic record of it), but Robin was there once again, playing another of Nora’s children and steering me around the stage as if I were an obedient pet. In that production, the role of Torvald, Nora’s tyrannical husband and the father of those two children, was played by that same fellow in the white shift from

The Emperor’s New Clothes

. In a case of art imitating life, my onstage father was my actual father. His name was Arthur Lithgow.

Thus it was that my curious life in entertainment was launched, before I was even conscious of it, on the same stage as my father. So it is with my father that I will begin.

A

rthur Lithgow had curious beginnings, too. He was born in the Dominican Republic, where, generations before, a clan of Scottish Lithgows had emigrated to seek their fortunes as sugar-growing landowners. I’m not sure whether these early Lithgows prospered, but they enthusiastically intermarried with the Dominican population. One recent day, as I was walking down a Manhattan sidewalk, a chocolate-brown Dominican cabdriver screeched to a stop, leaped out, and greeted me as his distant cousin.

Young Arthur got off to a bumpy start. Evidently, his father (my grandfather) was a bad businessman. He was naïve, overly trusting, and cursed with catastrophic bad luck. He and a partner teamed up on a far-fetched scheme to patent and peddle synthetic molasses. The partner absconded with their entire investment. My grandfather sued his erstwhile friend, lost the suit, and moved his family north to Boston, to start all over. At this point, his bad luck asserted itself. He fell victim to the Great Flu Epidemic of 1918, died within weeks, and left my grandmother a widow—penniless, a mother of four, and pregnant. Arthur was the third-oldest of her children. He was four years old. Growing up, he barely remembered even having a father.

But the situation for this forlorn family was far from hopeless. My grandmother, Ina B. Lithgow, was a trained nurse. She was smart, resourceful, and just as hard-nosed as my grandfather had been softheaded. He had left her with a large clapboard house in Melrose, Massachusetts, and she immediately set about putting it to good use. She flung open its doors and turned it into an old folks’ home. All four of her children were recruited to slave away as a grudging staff of peewee caregivers, in the hours before and after school. The oldest of these children was ten, the youngest was three. Child labor laws clearly did not apply when the survival of the family was at stake.

At some point in all this, Ina came to term. She gave birth to a baby daughter who only lived a matter of days. Swallowing her grief, and regaining her strength, she went right back to work.

To my father, Ina must have been downright scary as she fought to keep her household afloat. But fifty years later, when I was a child, little of the fierce, formidable pragmatist was left. She had mellowed into my gentle and adorable “Grammy.” Comfortable in that role, she was witty and mischievous, and entertained her grandchildren with long bedtime recitations of epic poems she had learned as a girl—“The Wreck of the Hesperus,” “The Skeleton in Armor,” “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.” Only recently did it occur to me that, fifty years before, in the midst of all that hardship, she must have bestowed the same storytelling riches on her own fatherless children.

I picture my father eight years old, bleary-eyed and dressed for bed in hand-me-down pajamas. It is an evening in 1922. He is with his two older sisters and his younger brother, huddling around their mother on a worn sofa in the darkened living room of their Melrose home. He is a pale, thin boy with reddish-brown hair. He is quiet, bookish, and a little melancholy, miscast in the role of “man of the house,” which fell to him when his father died. Tonight’s poem is “The Wonderful One-Hoss Shay,” by Oliver Wendell Holmes. I picture young Arthur listening with a kind of eager hunger, marking the meter, savoring the suspense, and devouring all those exotic new words. He is only a child, but I suspect he already knows, he can feel in his bones, that storytelling will define his later life.

And so it did. Growing into adolescence, Arthur commandeered a little room on the top floor of the Melrose house and immersed himself in books. Ghostly storytellers had found their most attentive listener: Rudyard Kipling, Washington Irving, Robert Louis Stevenson, Sir Walter Scott. And as he worked his way through all these timeworn treasures, he made a life-changing discovery. As an older man, my father described the moment when he “caught a fever”: he came across the plays of William Shakespeare. Reading from a single hefty volume of the Complete Works, the teenage boy proceeded to methodically plow through the entire vast canon.

A few years later, such literary passions sent Arthur westward to Ohio, to Antioch College, in Yellow Springs. There his love of storytelling evolved into a love of theater. At Antioch, he poured his energies into student productions. Cast as Hamlet in his senior year, he caught the eye of an infatuated freshman, a Baptist minister’s daughter from Rochester, New York, named Sarah Price. When Arthur graduated, he headed straight to New York City, where he joined the legions of aspiring young actors scrabbling for work in the depths of the Depression. Within months of his arrival, he was astonished to find Sarah Price on his doorstep, having dropped out of Antioch to follow him east. With no reasonable notion of what else to do, he married her. It was a marriage that was to last sixty-four years, until his death in 2004.

By the time my conscious memory kicks in, it was the late 1940s and the couple were back in Yellow Springs. In the intervening years, Arthur had turned his back on New York theater; he had taught at Vermont’s Putney School; he had worked in wartime industry in Rochester; and he had completed basic training in the U.S. Army. Just as he was about to be shipped out to the South Pacific, I was born. Arthur was now the father of three children. According to army policy, this made him eligible for immediate discharge. He seized the opportunity and rushed home to Rochester.

The next stop for the burgeoning young family was Ithaca, New York, where the G.I. Bill paid for Arthur’s master’s degree in playwriting at Cornell. A year later, he was working as a junior faculty member in English and drama at his alma mater, Antioch College. He was also producing plays for the Antioch Area Theatre in the old Yellow Springs Opera House. Among those plays were

A Doll’s House

and

The Emperor’s New Clothes

. A year after that, when I was approaching four years old, I start to remember.

The Lithgow family lived in Yellow Springs for ten years. When we moved away, I had just finished sixth grade. Those ten years would prove to be the longest stretch in one place of my entire childhood. I’ve only been back to Yellow Springs twice for fleeting visits, and the last visit was almost thirty years ago. Even so, it is the closest thing I have to a hometown.

I

n the first show of mine that I actually remember, I had a lousy part. I was the Chief Cook of the Castle in a third-grade school production of

The Sleeping Beauty

. It took place in broad daylight on a terrace outside The Antioch School. This was the lab school of Antioch College, where I was receiving a progressive, fun, and not very good education.

As the Chief Cook, my entire role consisted of chasing my assistant onto the stage with a rolling pin, then dropping to the ground and falling asleep for a hundred years at the moment Sleeping Beauty pricks her finger. I must have known what a bad part it was, but perhaps because of that I took particular care with my costume. I persuaded my father to make me a chef’s hat befitting the Chief Cook of the Castle. With surprising ingenuity, he folded a large piece of posterboard into a tall cylinder, then fashioned a puffy crown at the top with white crepe paper. The hat was almost as tall as I was. I was delighted.

“Now we’ll just cut it down to half this height and it’ll be perfect,” my father said.

“Oh, no, Dad!” I said. “Leave it!”

“But you’ll run onstage and it’ll fall off your head,” he reasoned.

“No, it won’t!” I insisted. “This is the hat of the Chief Cook of the Castle! It’s got to be very tall! Leave it!”

The next day, I carried the lordly hat into my classroom. My schoolmates were awestruck.

“It’s beautiful!” said Mrs. Parker. “But shouldn’t we cut it down to half this height? You’ll run onstage and it will fall off your head.”

“No, it won’t!” I exclaimed. “This is the hat of the Chief Cook of the Castle! The most important cook in the entire kingdom! It’s got to be very, very tall!”

My vehement arguments prevailed. The performance was that afternoon. When my cue came, I ran onstage and my hat immediately fell off my head. After the show, I chose not to answer the eight or ten people who asked, “Why did they give you such a tall hat?”

This was perhaps the first instance of the extravagant excess for which I would one day become so well known. But considering what my father was up to at the time, such grandiosity is hardly surprising.

Photograph by Axel Bahnsen. Courtesy Arthur Lithgow papers, Kent State University Libraries, Special Collections and Archives.

M

y father was producing Shakespeare on an epic scale. In the summer of 1951, in league with two of his faculty colleagues, he launched “Shakespeare Under the Stars,” otherwise known as the Antioch Shakespeare Festival. It was to last until 1957. The plays that had sparked the imagination of that lonely boy in an attic room in Melrose, Massachusetts, came to life on a platform stage beneath the twin spires of the stately Main Hall of Antioch College. In every one of those summers, my father’s company of avid young actors, many of them freshly minted graduates of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Tech, would achieve the impossible. Each season they would open seven Shakespeare plays in the course of nine weeks, rehearsing in the day and performing at night. Once all seven had opened, the company would perform them in rotating repertory, a different play every night of the week, for the final month of the summer. In 1951, the company began with a season of Shakespeare’s history plays. By 1957, they had performed all of the others as well, thirty-eight in all, many of them twice over. My father directed several of them and acted in several more, with an exuberant flamboyance that banished forever his boyhood shyness.