Dreamers of a New Day (34 page)

Read Dreamers of a New Day Online

Authors: Sheila Rowbotham

Similar disputes occurred in Britain, even though the economic and political context was quite different. Unemployment was high and the Labour Party accepted the regulation of industry. Concerned to halt the downward slide of women’s wage levels, the Standing Joint Committee of Industrial Women’s Organizations pushed for the unionization of women and state protection. In 1924, when the Labour Party was in power, their efforts resulted in a new Factory Act restricting the hours of women and young workers to a forty-eight-hour week.

65

Feminists in the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship opposed the Act, but this conflict did not assume the rigid and hostile form which emerged in America. NUSEC eventually dropped its position of outright opposition towards protection, in favour of a policy committed to consulting the needs of women in specific industries. Though in 1927 a group of egalitarian feminists left NUSEC in a dispute over protective legislation,

there was a range of views and demands among both feminists and labour women. Women in both groups could support equality and protection; Dora Russell, for instance, argued for protective legislation for all workers and special measures for women around maternity.

66

Behind the conflicts over women as workers lay dissimilar views about how women should be and live. A woman’s individual right to work was regarded by feminists who stressed equality as the touchstone of emancipation. Work for them not only brought economic independence, it constituted a vital means of expressing one’s abilities. In their view, appeals for protection fell into the old traps which presented women as essentially different and inferior to men. This was an elitist and abstract point, according to the reformers and socialists who focused on protection. They stressed the unfulfilling nature of most work within present conditions, and thought in terms of women’s basic well-being. Instead of regarding women workers as autonomous units, they took into account familial and kinship networks. The socialists among them argued for the need to curb capital’s power through state laws; the regulation of the working hours and conditions of women and children was assumed to be simply a first step.

Women’s labour problems were clear-cut and material: lack of options, low pay, and inequality at work and in the unions. However, efforts to solve them turned out be difficult, divisive and tactically messy. The conflicting remedies proposed included a free labour market, making demands for state intervention, encouraging contract compliance, consumer pressure, mutual self-help projects, social and community trade unionism, or combining community and workplace rebellions. The disagreements which arose in the course of agitation were not only about tactics; they reflected divergent approaches to gender, to the individual’s relation to society and indeed to work. Yet despite the failure to agree on common policies, these debates over what should be done about women’s work led some of the adventurers towards a wider process of rethinking which encompassed the scope of labour, what work might mean, how mass production might change, and how the economy could be structured.

9

Reworking Work

The intrepid middle-class women of the 1880s and 1890s had claimed access to careers regardless of personal sacrifice; ‘modern’ young women in the early twentieth century were convinced that paid employment would be one element in a life of self-realization and self-expression. For Emma Goldman, who doubted that work within the present system, even for supposedly privileged women, could be either fulfilling or emancipatory, this enthusiasm to enter the labour market was a delusion on the part of middle-class feminists. In 1914 she claimed that the extension of women’s education in the US was producing, not freedom and self-determination, but a multitude of genteel proletarians:

Every year our schools and colleges turn out thousands of competitors in the intellectual market, and everywhere the supply is greater than the demand. In order to exist, they must cringe and crawl and beg for a position. Professional women crowd the offices, sit around for hours, grow weary and faint with the search for employment, and yet deceive themselves with the delusion that they are superior to the working girl or that they are economically independent.

1

In the same year, the British anarchist Lily Gair Wilkinson similarly criticized ‘women of the privileged class’ for struggling to gain entry into the professions and ‘all those tortuous paths of life which men have cut out for themselves.’ Instead of wanting to become ‘lawyers, doctors, parsons, stockbrokers’ or even factory workers, Wilkinson believed that women should instead seek ‘freedom in communal life’.

2

Olive Schreiner’s influential

Woman and Labour

had adopted a quite different slant in 1911. ‘

We take all labour for our province!

’ asserted the

South African writer, endorsing feminists’ demands to enter male-defined employment with the declaration: ‘From the judge’s seat to the legislator’s chair; from the statesman’s closet to the merchant’s office; from the chemist’s laboratory to the astronomer’s tower, there is no post or form of toil for which it is not our intention to attempt to fit ourselves.’

3

Schreiner explained in her introduction that the book had occupied a large part of her life. She brought to

Woman and Labour

her own desperate longings for an individual identity, as well as her experience in wider social movements. The book enabled her to unravel a cluster of tangled strands around gender and work which she had encountered since the Ibsenite rebellions of the 1880s.

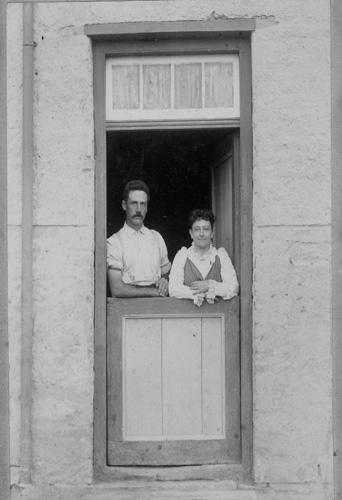

Cronwright and Olive Schreiner, 1894 (Carpenter

Collection, Sheffield Archives)

Woman and Labour

bridged the chasm which divided the new women’s assertion of individual autonomy from socialist theories of ‘the Woman Problem’, which stressed the class exploitation of women as workers or the social contribution of women as mothers. Examining the interactions between reproductive and productive activity, Schreiner observed that ‘modern social conditions’ were reducing the tendency for women to bear children as well as the numbers in each family, and therefore

mothering was now less likely to fill ‘the entire circle of female life’. As a result, the argument ‘that the main and continuous occupation of all women from puberty to age is the bearing and suckling of children’ was being undermined, along with the assumption ‘that this occupation must fully satisfy all her needs for social labour and activity.’ Such a perspective had become ‘an antiquated and unmitigated misstatement’; for Schreiner, it followed that a pattern of living must be devised so that women could be both mothers and workers.

4

Schreiner argued that the scope of women’s economic contribution had narrowed with the development of capitalism, reducing many women to ‘parasitism’. This contraction, she maintained, had been the motive force for what she called ‘the Woman’s Labour Movement’, which had arisen ‘among women of the more cultured and wealthy classes’ who were demanding that ‘professional, political and highly skilled labour [should be] thrown open to them’.

5

Cutting through the disputes over whether women should work or not, Schreiner demonstrated that they already did. She poked fun at the ‘lofty theorist’ who stood ‘before the drawing-room fire in spotless shirt-front and perfectly fitting clothes’, declaiming ‘upon the amplitude of woman’s work in life as child-bearer’.

6

The personification of the gender and class prejudices which determined how labour was seen and evaluated, he was oblivious to the sweated women workers and domestic servants who enabled him to philosophize in style, yet outraged by the thought of women doctors, legislators and professors. ‘It is not the labour, or the amount of labour, so much as the amount of reward that interferes with his ideal of the eternal womanly.’

7

The invisibility of poor women’s work was not an original idea. Anna Julia Cooper had made the same point in 1892 in

A View from the South

, in relation to black women’s work.

8

In the late 1890s the American anarchist Kate Austin, who was familiar with women’s work on farms, had noted how a double standard was applied to differing types of work:

Isn’t it queer that women can do the hardest kind of manual labor . . . and not a protest is heard. Should she take it into her head to study medicine, practise law, lecture or write on women’s rights . . . the whole masculine world is convulsed, wise old fossils write . . . ponderous papers on the subject, the home is in danger, woman is unsexing herself, getting coarse and masculine.

9

Schreiner’s broad view of labour as reproductive activity as well as production for wages, and the connections she made between paid and unpaid activity, were also not entirely new.

10

Housework had been acknowledged as work by the British feminist Ada Heather-Bigg in an 1894 article in the

Economic Journal

. Heather-Bigg argued that women’s employment had simply become visible through wage-earning: when men opposed women’s work, ‘what they object to is the wage-earning not the

work

of wives’.

11

The domestic labour of working-class women had also been noted by Schreiner’s friend Edward Carpenter, in his

Love’s Coming of Age

(1896).

12

While elements within

Woman and Labour

were already in circulation, the compound was Schreiner’s. She presented a challenge to the manner in which women’s paid and unpaid economic and social activities were undervalued. The book struck a profound chord among socialist and feminist women struggling to rethink work in relation to child-bearing, domestic life and consumption. Among them was the economic historian Alice Clark, who described

Woman and Labour

as ‘epoch-making’ in the Preface to her 1919

Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century

. For Clark the crux of Schreiner’s book was her insight into ‘the difference between reality and the commonly received generalisations as to women’s productive capacity’.

13

Clark belonged to an impressive network in the Fabian Women’s Group who were exploring how the daily lives of women had been excluded from the historical record. Based at the London School of Economics founded by Beatrice and Sidney Webb, this new generation of Fabian women combined an interest in history and social theory with an awareness of modern women’s dilemmas in balancing work with marriage and a family. Among them was the former student of Beatrice Webb, Bessie Leigh Hutchins, who, along with Mabel Atkinson, introduced Schreiner’s

Woman and Labour

to the Fabian Women’s Group. Hutchins, a member of the research group the Women’s Industrial Council, wrote in both mainstream economic journals and in the feminist

Englishwoman

on women’s work, and in 1915 was the author of a pioneering study,

Women in Modern Industry

.

14

Clark and Hutchins, along with Barbara Drake, were able to draw on the social and economic history pioneered by the Webbs, and, like the Webbs’, their interest in the present raised questions about the past. From this little group of Fabian women came the demand for work and motherhood.

Clark’s historical research documented how women’s productive activity had contracted with the shift from domestic industry. Her perspective moved the focus away from a purely political or legal definition of rights, undermining the nineteenth-century liberal view that women had steadily progressed towards emancipation. Clark believed historians and sociologists should not only look at politics, but consider economic and social development as a whole, including ‘the conditions under which the obscure mass of women live and fulfil their duties as human beings’.

15

This integrated approach conceptualized labour in terms of gaining a livelihood, rather than as paid employment alone. Clark adopted a mode of analysis which implicitly subverted existing ways of seeing gender relations and economic life.

While women like Schreiner and Clark theorized women’s labour in relation to social existence, others were imagining how work might be. The influence of Ruskin and Morris contributed to an interrogation about how work was done and what was produced, which ran in counterpoint to practical efforts to improve women’s work in the here and now. Morris’s conviction that work should be both fulfilling in the doing, and worth doing because it resulted in goods which were useful and beautiful, inspired the arts and crafts revival. Though the movement was led initially by men, women took up crafts such as embroidery, metalwork and stained glass. A few became designers and promoters of arts and crafts ideas. Julia Dawson, who set up the Clarion Guild of Handicraft in 1902, took her human-centred approach to technology from Morris, stressing that machines should be used to enhance the dignity of labour, rather than to de-skill the worker.

16