Dreamers of a New Day (35 page)

Read Dreamers of a New Day Online

Authors: Sheila Rowbotham

In America Mary Ware Dennett, who in 1894 became head of the new Department of Design and Decoration at Philadelphia’s Drexel Institute of Art, emphasized personal fulfilment through arts and crafts, telling her students that ‘Beauty, and art, which is the expression of beauty, should be a part of everyone’s life.’ She wanted art not ‘for art’s sake but for everybody’s sake’, believing that ‘All great art of the world has been the art of the people, and the trouble with our time is, that what art we have is confined to a very small class of people.’ While critical of the uniformity of machine-made goods, she did not dismiss machinery. Instead, Ware Dennett followed Morris in insisting that ‘machinery should be a servant to man, not make man its slave and attendant’.

17

Ethical aesthetics with a social edge drew her into reform circles during the 1900s, when she joined the Boston Consumers’ League and became

active in the women’s movement. She would later gain notoriety as a birth control campaigner.

Ellen Gates Starr, who helped Jane Addams to establish Hull House in Chicago, was an art bookbinder, and the two women enthusiastically incorporated arts and crafts into the work of the settlement. Both women had close links with Britain; Ruskin and Morris were key influences at Hull House, and Addams would later be in contact with the British arts and crafts designer Charles Ashbee, whose Guild and School of Handicraft sought to bring a new social meaning to labour. Addams demonstrated ingenuity in adapting arts and crafts to fit the needs of the Chicago poor; she regarded craftwork as a means of restoring self-respect among the older immigrants, dislocated in the strange foreign city.

18

She also hoped that enabling children who were being Americanized to appreciate their parents’ skills might help to overcome tensions in immigrant families, bringing respect for women as well as men. When the Hull House Labor Museum opened in 1900 displaying the diverse craft skills of Chicago’s immigrants, Addams remarked with pride: ‘The women of various nationalities enjoy the work and the recognition which it very properly brings them as mistresses of an old and honored craft.’

19

Addams saw the process of making as a means of remembering, reflecting how ‘the whirl of wheels recalls many a reminiscence and story of the old country, the telling of which makes a rural interlude in the busy town life’.

20

She felt sure that the dignity endowed by the recognition of skill could enable the immigrant poor to step with confidence into American society. The practical Addams wanted to help them relate to the new world, while retaining valued aspects of their earlier lives. Nevertheless, she also imagined them contributing towards the possibility of another kind of America. In Eileen Boris’s words, ‘The Labor Museum consolidated the past with the present to emphasize a cooperative vision of the future’.

21

Addams hoped that maintaining craft skills might humanize the conditions of machine production.

Ellen Gates Starr, however, was fiercely critical of machine-led production. Writing in

Hull House Maps and Papers

(1895), she noted that Ruskin and Morris had shown:

The product of a machine may be useful, and serve some purpose of information, but can never be artistic. As soon as a machine intervenes between the mind and its product, a hard, impassable barrier – a non-conductor of thought and emotion – is raised between the speaking and listening mind. If a man is made a machine, if his part is merely that of reproducing with mechanical exactness the design of somebody else, the effect is the same.

22

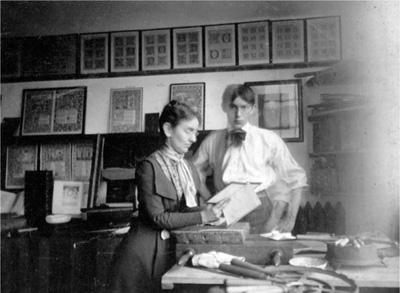

Ellen Gates Starr with Peter Verburg at the Hull House

bindery (Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College)

Starr’s romantic rejection of the machine landed her in the central contradiction of arts and crafts – the high costs which excluded the poor as consumers and producers. When she tried to teach her bookbinding skills at Hull House, the expensive materials proved well beyond the reach of local working-class women. Starr transposed her hostility to machine-based labour into a more general support for working-class resistance during the militant strike wave, which occurred between 1912–17.

The American social reformer Vida Scudder had discovered Ruskin when she studied at Oxford. After her return from Britain to the US, she helped to set up the College Settlements’ Association in 1889, and taught for the American University Extension movement in Boston’s Denison

House Settlement. Like many other middle-class settlement workers and reformers, she sought to overcome class divisions through closer human fellowship. Believing that this involved both social and personal changes, she interpreted Ruskin’s legacy as ‘the extension of the moral consciousness through all relations of production and consumption; the simplification of life, and the abandonment of luxury at least during the present crisis; the active devotion to some form of social service.’

23

Vida Dutton Scudder, 1884 (Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College)

Scudder’s ethical commitment led her to question the existing class structure which distorted relations between people in differing classes. Asserting a Whitmanite desire for individual fulfilment through democratic communion, she argued that the problem was how to realize the ‘craving’ for more ‘contact’ and ‘for full expression and reception of personality . . . in all the rich relations of actual life by the constant extension of fellowship’.

24

Practical engagement moved her leftwards; contact with labour struggles at Denison House was followed in 1903 by her work as an organizer in the Women’s Trade Union League. In 1912 she joined the Socialist Party, and inspired by the solidarity and fraternity of the Lawrence workers, became a trade union educator.

The rapidity of change in production methods and their impact on the labour process in the early years of the twentieth century encouraged some radical dreamers to engage in a total critique of the existing structures and purposes of work. In 1910 the anarchist Voltairine de Cleyre wrote in

Mother Earth

:

The Great idea of our age . . . is the

Much Making

of Things; not the joy of spending living energy in creative work; rather the shameless, merciless driving and over driving, wasting and draining of the last bit of energy, only to produce heaps and heaps of things – things ugly, things harmful, things useless and at the best largely unnecessary.

25

For de Cleyre, production, consumption and ways of living were integrally linked. Emma Goldman’s perspective was similarly interrelated. She was scornful not simply of the kind of objects made under the capitalist system of production, but of the impact of exploitation and competition on human well-being and culture. ‘Real wealth consists in things of utility and beauty, in things that help to create strong beautiful bodies and surroundings inspiring to live in.’ Existing work resulted only in ‘gray and hideous things, reflecting a dull and hideous existence’.

26

Worst of all, modern production methods were reducing workers to ‘brainless automations’.

27

De Cleyre and Goldman’s loathing of the mass production methods which were taking hold in America was echoed in Britain. The British anarchist Lily Gair Wilkinson protested at the repressive consequences of the acute awareness of time which governed offices as well as factories. Writing in Margaret Sanger’s

Woman Rebel

, she described graphically the impact of a time-controlled consciousness:

As you stand listening to the menace of the clock and wondering whether you will break free or trudge back to the office, you have a sudden revelation. You realize that while there are men and women who hold from others the means of life – the rich surface of the earth and the means of cultivating that richness – so long there will be no freedom for the others who possess none at all. For possession by a few gives power to the few to control the lives of the millions who are dispossessed, and to bring them into life-long bondage.

28

In her pamphlet

Woman’s Freedom

(1914), Wilkinson echoed Edward Carpenter in calling for a return to a ‘simpler life’, which she believed

would be more ‘wholesome’.

29

Wilkinson favoured handicrafts produced at home along with agriculture. She imagined men as well as women living together and working together at home.

The bohemians of Greenwich Village borrowed some elements of arts and crafts stress on creativity in labour, as well as the anarchist rejection of the clear-cut demarcation between work and leisure. Art, labour, politics, creativity and sex were at one in the inchoate milieu of bohemia. Mabel Dodge Luhan’s restless search for experience epitomized the rejection of boundaries, while the writer Susan Glaspell insisted that in the Village, ‘Life was all of a piece, work not separated from play’.

30

Although political and social change formed part of the bohemian agenda, the emphasis was on personally living against the grain, prefiguring fusion amidst fragmentation.

Despite their multiple outlooks, adventurers influenced by Ruskin, Morris and arts and crafts sought to integrate work and life, conceiving a human-centred technology, an everyday aesthetic of use and pleasure, and new kinds of democracy in daily encounters. Asking questions about work led them to examine received ideas about the body and human relationships, the environment and culture. Some of the more radical dreamers also rejected the contemporary drive for greater productivity. At this point, however, they faltered; for their absolute renunciation offered no way in which they could engage with the transformation which was rapidly overtaking them.

Some American women reformers, in contrast, embraced Taylorist production methods as an advance on the arbitrary coercion which marked relations between workers and employers in factories and sweatshops. Lillian Gilbreth believed that scientific management offered a far preferable form of industrial organization, because it could recognize workers’ level of productivity fairly and reward them accordingly. She also saw the regulation of input as a means of preventing fatigue. Working with husband Frank as an industrial consultant, Gilbreth pioneered the human relations aspects of scientific management in her studies of the engineering industry, and in her later work on the clerical, retail and laundry sectors.

31

Her 1914 study

The Psychology of Management: The Function of the Mind in Determining, Teaching and Installing Methods of Least Waste

merged an interest in psychology with her own theories of home-making. Gilbreth argued that close observation of the physical expenditure of energy had to be complemented by management taking into account the

interconnection between the worker’s mind and body. This focus on the needs of individual workers led her to advocate rest breaks. She also pioneered the ergonomic study of how to improve lighting and chair design, devising better working positions in order to minimize fatigue and backache. Gilbreth set out to persuade both workers and employers that ergonomics could be beneficial in human terms, while also raising productivity.

32

Employers were apt to take on those aspects of Taylorism which enabled them to increase output and minimize workers’ control, sooner than measures aiming to enhance the welfare of workers. However, under attack during the early twentieth century from vigorous ‘muckraking’ journalists who denounced corporate greed, some big employers perceived that the old, blatant ‘tooth and claw’ style of capitalism required a new look. They became prepared to incorporate some of their critics’ proposals, so long as there were benefits for their companies. In 1902, when Ida Tarbell was engaged on research into the Standard Oil Company, the charismatic and charming boss of Standard Oil, Henry Rogers – ‘tall, muscular, lithe as an Indian’ – met with her secretly. Rogers worked hard to win her support for company policy, graphically evoking the Iowa hills where she had lived as a child and where he had laid the basis for his fortune in oil.

33

Tarbell commented in her autobiography,

All in a Day’s Work

: ‘Mr Rogers may be regarded, I think, as the first public relations counsel of the Standard Oil Company.’ She was ‘the first subject on which the new policy was tried’.

34

Rogers had softened her critique of the corporate elite.