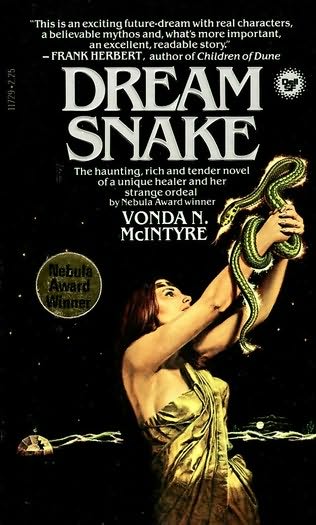

Dreamsnake

Vonda N. McIntyre

contents

Published by DELL PUBLISHING CO., INC

.

Copyright © 1978 by Vonda N. McIntyre

Dell ® TM 681510, Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

ISBN: 0-440-11729-1

Reprinted by arrangement with

Houghton Mifflin Company Printed in the United States of America

First Dell printing—June 1979

A portion of this book originally appeared in ANALOG Science Fiction/Science

Fact.

To my parents

Chapter 1

The little boy was frightened. Gently, Snake touched his hot forehead. Behind

her, three adults stood close together, watching, suspicious, afraid to show

their concern with more than narrow lines around their eyes. They feared Snake

as much as they feared their only child’s death. In the dimness of the tent, the

strange blue glow of the lantern gave no reassurance.

The child watched with eyes so dark the pupils were not visible, so dull that

Snake herself feared for his life. She stroked his hair. It was long, and very

pale, dry and irregular for several inches near the scalp, a striking color

against his dark skin. Had Snake been with these people months ago, she would

have known the child was growing ill.

“Bring my case, please,” Snake said.

The child’s parents started at her soft voice. Perhaps they had expected the

screech of a bright jay, or the hissing of a shining serpent. This was the first

time Snake had spoken in their presence. She had only watched, when the three of

them had come to observe her from a distance and whisper about her occupation

and her youth; she had only listened, and then nodded, when finally they came to

ask her help. Perhaps they had thought she was mute.

The fair-haired younger man lifted her leather case. He held the satchel away

from his body, leaning to hand it to her, breathing shallowly with nostrils

flared against the faint smell of musk in the dry desert air. Snake had almost

accustomed herself to the kind of uneasiness he showed; she had already seen it

often.

When Snake reached out, the young man jerked back and dropped the case. Snake

lunged and barely caught it, gently set it on the felt floor, and glanced at him

with reproach. His partners came forward and touched him to ease his fear. “He

was bitten once,” the dark and handsome woman said. “He almost died.” Her tone

was not of apology, but of justification.

“I’m sorry,” the younger man said. “It’s—” He gestured toward her; he was

trembling, but trying visibly to control himself. Snake glanced to her shoulder,

where she had been unconsciously aware of the slight weight and movement. A tiny

serpent, thin as the finger of a baby, slid himself around her neck to show his

narrow head below her short black curls. He probed the air with his trident

tongue, in a leisurely manner, out, up and down, in, to savor the taste of the

smells. “It’s only Grass,” Snake said. “He can’t hurt you.” If he were bigger,

he might be frightening: his color was pale green, but the scales around his

mouth were red, as if he had just feasted as a mammal eats, by tearing. He was,

in fact, much neater.

The child whimpered. He cut off the sound of pain; perhaps he had been told

that Snake, too, would be offended by crying. She only felt sorry that his

people refused themselves such a simple way of easing fear. She turned from the

adults, regretting their terror of her but unwilling to spend the time it would

take to persuade them to trust her. “It’s all right,” she said to the little

boy. “Grass is smooth, and dry, and soft, and if I left him to guard you, even

death could not reach your bedside.” Grass poured himself into her narrow, dirty

hand, and she extended him toward the child. “Gently.” He reached out and

touched the sleek scales with one fingertip. Snake could sense the effort of

even such a simple motion, yet the boy almost smiled.

“What are you called?”

He looked quickly toward his parents, and finally they nodded.

“Stavin,” he whispered. He had no breath or strength for speaking.

“I am Snake, Stavin, and in a little while, in the morning, I must hurt you.

You may feel a quick pain, and your body will ache for several days, but you’ll

be better afterward.”

He stared at her solemnly. Snake saw that though he understood and feared

what she might do, He was less afraid than if she had lied to him. The pain must

have increased greatly as his illness became more apparent, but it seemed that

others had only reassured him, and hoped the disease would disappear or kill him

quickly.

Snake put Grass on the boy’s pillow and pulled her case nearer. The adults

still could only fear her; they had had neither time nor reason to discover any

trust. The woman of the partnership was old enough that they might never have

another child unless they partnered again, and Snake could tell by their eyes,

their covert touching, their concern, that they loved this one very much. They

must, to come to Snake in this country.

Sluggish, Sand slid out of the case, moving his head, moving his tongue,

smelling, tasting, detecting the warmths of bodies.

“Is that—?” The eldest partner’s voice was low and wise, but terrified, and

Sand sensed the fear. He drew back into striking position and sounded his rattle

softly. Snake stroked her hand along the floor, letting the vibrations distract

him, then moved her hand up and extended her arm. The diamondback relaxed and

wrapped his body around and around her wrist to form black and tan bracelets.

“No,” she said. “Your child is too ill for Sand to help. I know it’s hard,

but please try to be calm. This is a fearful thing for you, but it is all I can

do.”

She had to annoy Mist to make her come out. Snake rapped on the bag, and

finally poked her twice. Snake felt the vibration of sliding scales, and

suddenly the albino cobra flung herself into the tent. She moved quickly, yet

there seemed to be no end to her. She reared back and up. Her breath rushed out

in a hiss. Her head rose well over a meter above the floor. She flared her wide

hood. Behind her, the adults gasped, as if physically assaulted by the gaze of

the tan spectacle design on the back of Mist’s hood. Snake ignored the people

and spoke to the great cobra, focusing her attention by her words.

“Furious creature, lie down. It’s time to earn thy dinner. Speak to this

child and touch him. He is called Stavin.”

Slowly, Mist relaxed her hood and allowed Snake to touch her. Snake grasped

her firmly behind the head and held her so she looked at Stavin. The cobra’s

silver eyes picked up the blue of the lamplight.

“Stavin,” Snake said, “Mist will only meet you now. I promise that this time

she will touch you gently.”

Still, Stavin shivered when Mist touched his thin chest. Snake did not

release the serpent’s head, but allowed her body to slide against the boy’s. The

cobra was four times longer than Stavin was tall. She curved herself in stark

white loops across his swollen abdomen, extending herself, forcing her head

toward the boy’s face, straining against Snake’s hands. Mist met Stavin’s

frightened stare with the gaze of lidless eyes. Snake allowed her a little

closer.

Mist nicked out her tongue to taste the child.

The younger man made a small, cut-off, frightened sound. Stavin flinched at

it, and Mist drew back, opening her mouth, exposing her fangs, audibly thrusting

her breath through her throat. Snake sat back on her heels, letting out her own

breath. Sometimes, in other places, the kinfolk could stay while she worked.

“You must leave,” she said gently. “It’s dangerous to frighten Mist.”

“I won’t—”

“I’m sorry. You must wait outside.”

Perhaps the fair-haired youngest partner, perhaps even Stavin’s mother, would

have made the indefensible objections and asked the answerable questions, but

the white-haired man turned them and took their hands and led them away.

“I need a small animal,” Snake said as he lifted the tent flap. “It must have

fur, and it must be alive.”

“One will be found,” he said, and the three parents went into the glowing

night. Snake could hear their footsteps in the sand outside.

Snake supported Mist in her lap and soothed her. The cobra wrapped herself

around Snake’s waist, taking in her warmth. Hunger made the cobra even more

nervous than usual, and she was hungry, as was Snake. Coming across the

black-sand desert, they had found sufficient water, but Snake’s traps had been

unsuccessful. The season was summer, the weather was hot, and many of the furry

tidbits Sand and Mist preferred were estivating. Since she had brought them into

the desert, away from home, Snake had begun a fast as well.

She saw with regret that Stavin was more frightened now. “I’m sorry to send

your parents away,” she said. “They can come back soon.”

His eyes glistened, but he held back the tears. “They said to do what you

told me.”

“I would have you cry, if you are able,” Snake said. “It isn’t such a

terrible thing.” But Stavin seemed not to understand, and Snake did not press

him; she thought his people must teach themselves to resist a difficult land by

refusing to cry, refusing to mourn, refusing to laugh. They denied themselves

grief, and allowed themselves little joy, but they survived.

Mist had calmed to sullenness. Snake unwrapped her from her waist and placed

the serpent on the pallet next to Stavin. As the cobra moved, Snake guided her

head, feeling the tension of the striking-muscles. “She will touch you with her

tongue,” she told Stavin. “It might tickle, but it will not hurt. She smells

with it, as you do with your nose.”

“With her tongue?”

Snake nodded, smiling, and Mist flicked out her tongue to caress Stavin’s

cheek. Stavin did not flinch; he watched, his child’s delight in knowledge

briefly overcoming pain. He lay perfectly still as Mist’s long tongue brushed

his cheeks, his eyes, his mouth. “She tastes the sickness,” Snake said. Mist

stopped fighting the restraint of her grasp, and drew back her head. Snake sat

on her heels and released the cobra, who spiraled up her arm and laid herself

across her shoulders.

“Go to sleep, Stavin,” Snake said. “Try to trust me, and try not to fear the

morning.”

Stavin gazed at her for a few seconds, searching for truth in Snake’s pale

eyes. “Will Grass watch?”

She was startled by the question, or, rather, by the acceptance behind the

question. She brushed his hair from his forehead and smiled a smile that was

tears just beneath the surface. “Of course.” She picked Grass up. “Watch this

child, and guard him.” The dreamsnake lay quiet in her hand, and his eyes

glittered black. She laid him gently on Stavin’s pillow.

“Now sleep.”

Stavin closed his eyes, and the life seemed to flow out of him. The

alteration was so great that Snake reached out to touch him, then saw that he

was breathing, slowly, shallowly. She tucked a blanket around him and stood up.

The abrupt change in position dizzied her; she staggered and caught herself.

Across her shoulder, Mist tensed.

Snake’s eyes stung and her vision was oversharp, fever-clear. The sound she

imagined she heard swooped in closer. She steadied herself against hunger and

exhaustion, bent slowly, and picked up the leather case. Mist touched her cheek

with the tip of her tongue.

She pushed aside the tent flap and felt relief that it was still night. She

could stand the daytime heat, but the brightness of the sun curled through her,

burning. The moon must be full; though the clouds obscured everything, they

diffused the light so the sky appeared gray from horizon to horizon. Beyond the

tents, groups of formless shadows projected from the ground. Here, near the edge

of the desert, enough water existed so clumps and patches of bush grew,

providing shelter and sustenance for all manner of creatures. The black sand,

which sparkled and blinded in the sunlight, at night was like a layer of soft

soot. Snake stepped out of the tent, and the illusion of softness disappeared;

her boots slid crunching into the sharp hard grains.

Stavin’s family waited, sitting close together between the dark tents that

clustered in a patch of sand from which the bushes had been ripped and burned.

They looked at her silently, hoping with their eyes, showing no expression in

their faces. A woman somewhat younger than Stavin’s mother sat with them. She

was dressed, as they were, in long loose desert robes, but she wore the only

adornment Snake had seen among these people: a leader’s circle, hanging around

her neck on a leather thong. She and Stavin’s eldest parent were marked close

kin by their similarities: sharp-cut planes of face, high cheekbones, his hair

white and hers graying early from deep black, their eyes the dark brown best

suited for survival in the sun. On the ground by their feet a small black animal

jerked sporadically against a net, and infrequently gave a shrill weak cry.

“Stavin is asleep,” Snake said. “Do not disturb him, but go to him if he

wakes.”

Stavin’s mother and the youngest partner rose and went inside, but the older

man stopped before her. “Can you help him?”

“I hope so. The tumor is advanced, but it seems solid.” Her own voice sounded

removed, ringing slightly false, as if she were lying. “Mist will be ready in

the morning.” She still felt the need to give him reassurance, but she could

think of none.

“My sister wished to speak with you,” he said, and left them alone, without

introduction, without elevating himself by saying that the tall woman was the

leader of this group. Snake glanced back, but the tent flap fell shut. She was

feeling her exhaustion more deeply, and across her shoulders Mist was, for the

first time, a weight she thought heavy.

“Are you all right?”

Snake turned. The woman moved toward her with a natural elegance made

slightly awkward by advanced pregnancy. Snake had to look up to meet her gaze.

She had small, fine lines at the corners of her eyes and beside her mouth, as if

she laughed, sometimes, in secret. She smiled, but with concern. “You seem very

tired. Shall I have someone make you a bed?”

“Not now,” Snake said, “not yet. I won’t sleep until afterward.”

The leader searched her face, and Snake felt a kinship with her in their

shared responsibility.

“I understand, I think. Is there anything we can give you? Do you need aid

with your preparations?”

Snake found herself having to deal with the questions as if they were complex

problems. She turned them in her tired mind, examined them, dissected them, and

finally grasped their meanings. “My pony needs food and water—”