Drink (48 page)

Authors: Iain Gately

23 EMANCIPATION

The same spirits which make a white man drunk make a black man drunk too. Indeed, in this I can find proof of my identity with the family of man.

—Frederick Douglass

When there shall be neither a slave nor a drunkard

on the earth—how proud the title of that Land,

which may truly claim to be the birthplace and the

cradle of both those revolutions, that shall have

ended in that victory. How nobly distinguished that

People, who shall have planted, and nurtured to

maturity, both the political and moral freedom of

their species.

on the earth—how proud the title of that Land,

which may truly claim to be the birthplace and the

cradle of both those revolutions, that shall have

ended in that victory. How nobly distinguished that

People, who shall have planted, and nurtured to

maturity, both the political and moral freedom of

their species.

—Abraham Lincoln

Many American visitors to the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1855 were likely to have carried one or both of two recent publishing sensations as reading material for the transatlantic voyage. While one of these books,

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

(1852), by Harriet Beecher Stowe, was also a best-seller in Europe, the other,

Ten Nights in a Bar-Room

(1854), by T. S. Arthur, was famous only in America, where four hundred thousand copies were in circulation. A strangely compelling and stridently Prohibitionist novel,

Ten Nights in a Bar-Room

was indicative of the differences in attitudes toward alcohol that had developed between the United States and France. Its readers were concentrated in the eastern and old western states, where the myriad temperance organizations founded in the first half of the nineteenth century had succeeded in turning their cause from a moral into a political issue. The debate had moved on from Communion wine to coercion. Drink was bad, and since people were too weak to resist it, it must be denied to them. Wherever there was alcohol on sale there would be drunkards and wherever there were drunkards there was poverty, squalor, and violence. The only way, therefore, to forestall impending chaos was to outlaw drinking places. Temperance candidates stood at every election, great or small, with the aim, if successful, of prohibiting the retailing of alcohol.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

(1852), by Harriet Beecher Stowe, was also a best-seller in Europe, the other,

Ten Nights in a Bar-Room

(1854), by T. S. Arthur, was famous only in America, where four hundred thousand copies were in circulation. A strangely compelling and stridently Prohibitionist novel,

Ten Nights in a Bar-Room

was indicative of the differences in attitudes toward alcohol that had developed between the United States and France. Its readers were concentrated in the eastern and old western states, where the myriad temperance organizations founded in the first half of the nineteenth century had succeeded in turning their cause from a moral into a political issue. The debate had moved on from Communion wine to coercion. Drink was bad, and since people were too weak to resist it, it must be denied to them. Wherever there was alcohol on sale there would be drunkards and wherever there were drunkards there was poverty, squalor, and violence. The only way, therefore, to forestall impending chaos was to outlaw drinking places. Temperance candidates stood at every election, great or small, with the aim, if successful, of prohibiting the retailing of alcohol.

The temperance platform was dramatized in

Ten Nights in a Bar-Room,

most of whose action takes place in the Sickle and Sheaf Tavern in a small town named Cedarville, which the narrator visits over a period of ten years, during which time the inhabitants of the once-pretty settlement are gradually ruined by the malevolent influence of the drinking house in their midst. The book features all the established emblems of temperance noir writing—the corruption of youth, several murders, a drunk redeemed at his daughter’s deathbed, d.t.’s-inspired hallucinations (including a giant toad under the bedclothes), and so on; it also rehearses protemperance arguments by placing them in the mouths of casual drinkers, as the following example, masquerading as a conversation about politics between strangers, illustrates:

Ten Nights in a Bar-Room,

most of whose action takes place in the Sickle and Sheaf Tavern in a small town named Cedarville, which the narrator visits over a period of ten years, during which time the inhabitants of the once-pretty settlement are gradually ruined by the malevolent influence of the drinking house in their midst. The book features all the established emblems of temperance noir writing—the corruption of youth, several murders, a drunk redeemed at his daughter’s deathbed, d.t.’s-inspired hallucinations (including a giant toad under the bedclothes), and so on; it also rehearses protemperance arguments by placing them in the mouths of casual drinkers, as the following example, masquerading as a conversation about politics between strangers, illustrates:

“Did not you vote the anti-temperance ticket at the last election?”

“I did,” was the answer; “and from principle.”

“On what were your principles based?” was inquired.

“On the broad foundations of civil liberty.”

“The liberty to do good or evil, just as the individual may choose?”

“I would not like to say that. There are certain evils against which there can be no legislation that would not do harm. No civil power in this country has the right to say what a citizen shall eat or drink.”

“But may not the people, in any community, pass laws, through their delegated law-makers, restraining evil-minded persons from injuring the common good?”

“Oh, certainly—certainly.”

“And are you prepared to affirm, that a drinking-shop, where young men are corrupted, aye, destroyed, body and soul—does not work an injury to the common good?”

“Ah! but there must be houses of public entertainment.”

“No one denies this. But can that be a really Christian community which provides for the moral debasement of strangers, at the same time that it entertains them? Is it necessary that, in giving rest and entertainment to the traveler, we also lead him into temptation?”

The discussion ends with the temperance advocate predicting an apocalypse for the United States unless action is taken against taverns:

Of little value, my friend, will be, in far too many cases, your precepts, if temptation invites our sons at almost every step of their way through life. Thousands have fallen, and thousands are now tottering, soon to fall. Your sons are not safe; nor are mine. We cannot tell the day nor the hour when they may weakly yield to the solicitation of some companion, and enter the wide open door of ruin. And are we wise and good citizens to . . . hesitate over some vague ideal of human liberty when the sword is among us, slaying our best and dearest? Sir! while you hold back from the work of staying the flood that is desolating our fairest homes, the black waters are approaching your own doors.

The other great political issue of the day was slavery, the principal theme of

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

. Superficially, the prohibition and abolition movements had much in common. Each perceived their cause as being a moral crusade, and a number of individuals served both. The Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, for example, brother of the author of

Uncle Tom’s Cabin,

preached temperance and raised funds to arm abolitionists in Kansas. However, many temperance agitators thought it more important to free the southern states from the curse of drinking than to encourage them to free their slaves, and they indulged in shameful equivocations in order to keep abolition and abstinence apart. According, for example, to John Gough, the Washington celebrity, alcoholism was by far the worst kind of servitude: “Ah, yes, physical slavery is an awful thing,” he noted in

Platform Echoes,

a volume of memoirs, but a “man may be bought or sold in the market and yet be a freer man than he who sells him.”

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

. Superficially, the prohibition and abolition movements had much in common. Each perceived their cause as being a moral crusade, and a number of individuals served both. The Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, for example, brother of the author of

Uncle Tom’s Cabin,

preached temperance and raised funds to arm abolitionists in Kansas. However, many temperance agitators thought it more important to free the southern states from the curse of drinking than to encourage them to free their slaves, and they indulged in shameful equivocations in order to keep abolition and abstinence apart. According, for example, to John Gough, the Washington celebrity, alcoholism was by far the worst kind of servitude: “Ah, yes, physical slavery is an awful thing,” he noted in

Platform Echoes,

a volume of memoirs, but a “man may be bought or sold in the market and yet be a freer man than he who sells him.”

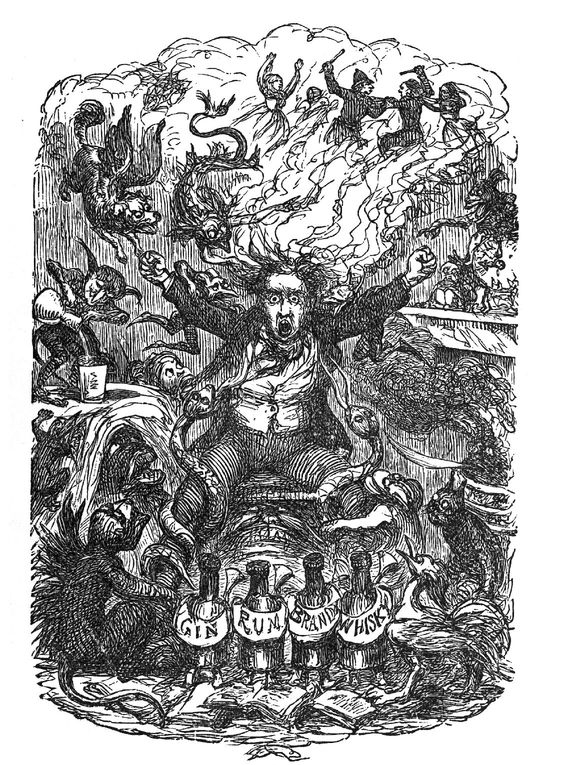

IN THE MONSTER’S CLUTCHES. Body and Brain on Fire.

Not only did the temperance movement place politics before humanity, it also rejected an entire community of potential supporters. African Americans, free or in bondage, were staunch opponents of alcohol. Drink had grim historic links with their presence in the United States—many had ancestors who had been traded for a keg of rum. Furthermore, slaves with drunken owners often suffered arbitrary acts of brutality, which contributed to their loathing of alcohol. Finally, drink was used as an instrument of oppression on the plantations. At Christmas, slaves were given “holidays,” supplied with spirits, and encouraged to get drunk, in the belief that if allowed to indulge themselves every now and then, they would see their enslavement as less cruel. According to Frederick Douglass, the aim of this practice was to “disgust the slave with freedom, by allowing him to see only the abuse of it.”

Sobriety, alongside education and domestic economy, had been recognized at the 1831 First Annual Convention of the People of Color, held in Philadelphia, as a key attribute most likely to raise African Americans to “a proper rank and standing amongst men.” They were, however, forced to form their own temperance organizations, and these were sometimes the objects of racist violence, as for example in 1841, when a white mob attacked the members of the Moyamensing Temperance Society who were celebrating the final manumission of slaves in British dominions. Despite such harassment, free blacks kept faith with abstinence, hoping by their sobriety to prove they were worthy of equality.

The pursuit of temperance in the United States was sidelined by its Civil War, during which a laissez-faire approach to drinking prevailed. Convictions pro and contra alcohol were held with equal force and were equally tolerated by each side. Lincoln was a teetotaler, as was Confederate general Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, who explained his abstinence thus: “I like strong drink—so I never touch it.” General Ulysses S. Grant, in contrast, was very nearly an alcoholic. Whether or not a man took liquor was up to him, and if it helped him to function better, it was accepted as a harmless idiosyncrasy. The spirit of the times is reflected by the response of Abraham Lincoln to a complaint that General Grant drank too much. Rather than promising to make him abstain, Lincoln vowed that he would ask “the quartermaster of the army to lay in a large stock of the same kind of liquor, and would direct him to furnish a supply to some of my other generals who have never yet won a victory.”

Both sides supplied their troops with alcohol. An unofficial whiskey ration was issued to the Union army,

51

and the Confederates supplied their men with spirits from time to time. In terms of supply, the Union armies were ahead. Despite the Maine law and its cohorts, there were still more distilleries north of the Mason-Dixon Line than in the Rebel states. Moreover, after it had assumed command of the ocean and the Mississippi River, the Union could import at will and deny the South the same resource. This blockade, in combination with the deliberate despoliation of agriculture in Confederate territory, dried up the Rebel supply of alcohol, so that by the time of the war’s conclusion many Confederate soldiers had become temperate through force of circumstance. Indeed, fluctuations in the supply of alcohol in the South closely reflected its fortunes in the war.

51

and the Confederates supplied their men with spirits from time to time. In terms of supply, the Union armies were ahead. Despite the Maine law and its cohorts, there were still more distilleries north of the Mason-Dixon Line than in the Rebel states. Moreover, after it had assumed command of the ocean and the Mississippi River, the Union could import at will and deny the South the same resource. This blockade, in combination with the deliberate despoliation of agriculture in Confederate territory, dried up the Rebel supply of alcohol, so that by the time of the war’s conclusion many Confederate soldiers had become temperate through force of circumstance. Indeed, fluctuations in the supply of alcohol in the South closely reflected its fortunes in the war.

At the beginning of the conflict, the mood of the Confederate volunteers who had flocked to its banner had been buoyant. Sixty percent of them were farmers or their sons, in the majority from small communities, who had seldom, if ever, seen a city or a crowd. A holiday atmosphere prevailed as they assembled and traveled to the front. The excitement of events led many who had been temperate at home to experiment on the way to war and to fall “into the delusion that drinking was excusable, if not necessary, in the army.” The initial elation, and a ready supply of alcohol with which to sustain it, alarmed the Confederate command. In 1861 General Braxton Bragg prohibited the sale of alcohol within five miles of Pensacola, where his troops were stationed. Drunkenness, in his opinion, was causing “demoralization, disease, and death” among them: “We have lost more valuable lives at the hands of the whiskey sellers than by the balls of our enemies.” His example was recommended to his fellow officers, and similar prohibitions were installed in other Rebel camps. They do not seem to have been enforced with any great severity. Alcohol was smuggled into camp, at times blatantly, at others discreetly—injected into a watermelon (a large one could absorb a half gallon of whiskey) or tipped down the barrel of a musket that was held at present arms until its bearer reached his tent. Punishments for carrying liquor into camp were not, by military standards of discipline, severe. No one was flogged or shot for drinking. Private Henry Jones, for instance, found guilty of drunkenness at his post in Tullahoma, Tennessee, was made to spend two hours a day, every day for a month, standing on the head of a barrel with an empty whiskey bottle hanging from his neck.

The first Christmas of the war was celebrated in the South with spirits and song. Whiskey acquired the nickname among some Rebels as “Oh-be-joyful,” under which guise it pops up in their letters home. Quality, however, was on the wane: “The general Davis sent up a barrel of whiskey to the camp,” reported one trooper, “but it was such villainous stuff that only the old soakers could stomach it.” The following year whiskey could still be found to celebrate the Nativity, but shortages of other supplies rendered its enjoyment imperfect. One Texan rebel’s diary entry for December 25, 1862, lamented the absence of eggs to make eggnog and observed, “If it was in my power I would condemn every old hen on the Rio Grande to six months confinement in close-coop for the non conformance of a most sacred duty.” By 1863, however, not only the mixers but also oh-be-joyful was in short supply. Post-Vicksburg, the Mississippi was controlled by the Union, thus cutting off Taos Lightning and other such delicacies, and within the Confederate heartland stills were being broken up for their copper, which was used to forge bronze cannon.

At the same time that supplies of liquor were diminishing, the temperance movement began to appear in force in Southern camps. While Bibles had been issued to every soldier by various benevolent societies at the start of the conflict, these were neglected in initial years, when it seemed that the next Rebel victory would force the Union to sue for peace. However, as reverses on the battlefield increased, a religious revival took place among the Confederate ranks, which was supported by a plethora of religious tracts, whose publishers maintained a more efficient distribution network than the suppliers of such secular comforts as clothing and rations. These tracts provided moral as well as spiritual guidance to the Rebel troops and sought to arm them against the evils of swearing, gambling, and drinking. One such,

Lincoln and Liquor,

put a new spin on the slave-to-alcohol argument—why fight for freedom from Washington, only to surrender to the whiskey bottle? The pamphlet also predicted crop failures if they continued to be wasted in the manufacture of “distilled damnation.” The revival and the pamphleteering seem to have diminished demand for now-scarce alcohol. One rebel soldier wrote to his mother and sister from the front thanking them for various gifts, including some whiskey, but warning them, “The Whiskey you may depend will be used moderately as I belong to the Temperance society of whom Gen Braxton Bragg is president.”

Lincoln and Liquor,

put a new spin on the slave-to-alcohol argument—why fight for freedom from Washington, only to surrender to the whiskey bottle? The pamphlet also predicted crop failures if they continued to be wasted in the manufacture of “distilled damnation.” The revival and the pamphleteering seem to have diminished demand for now-scarce alcohol. One rebel soldier wrote to his mother and sister from the front thanking them for various gifts, including some whiskey, but warning them, “The Whiskey you may depend will be used moderately as I belong to the Temperance society of whom Gen Braxton Bragg is president.”

Other books

Susan King - [Celtic Nights 01] by The Stone Maiden

Spirit Week Showdown by Crystal Allen

The Mothman Prophecies by John A. Keel

The Circle by Elaine Feinstein

Make Me by Tamara Mataya

You and I Alone by Melissa Toppen

Pretty Little Liars by Sara Shepard

The Nanny Solution by Barbara Phinney

My Funny Valentina by Curry, Kelly

The Drowned World by J. G. Ballard