Drink (50 page)

Authors: Iain Gately

However, while the temperance movement was advancing on several fronts, it was forced to give ground to the beer lobby in other places. It had been the fervent hope of the drys that the American Centennial Exhibition, staged in Philadelphia in 1876, would be an alcohol-free event, and they lobbied to have brewers excluded from its agricultural displays. However, they were outflanked by their opponents, who petitioned for, and were awarded, a separate edifice of their own—the Brewers Hall, a magnificent structure of wrought iron and glass. It was graced with a monumental portico, reminiscent of Napoléon’s Arc de Triomphe, which sheltered an immense statue of Gambrinus, the medieval king and legendary beer drinker of Bohemia, represented in a posture of victory. The Brewers Hall was one of the most popular attractions of the Centennial Exhibition, in particular its icehouse, which featured chilled beers from around the world. In addition to refreshing their visitors, the brewers supplied them with propaganda, which explained that the duties they paid were by far the largest source of internal revenue in the United States: That “a brewer is just as necessary to the commonweal as a butcher, a baker, a tailor, a builder, or any other economic industry, is proven by the present position of the trade in the United States.”

24 IMPERIAL PREFERENCE

Here with a loaf of bread beneath the Bough,

A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse, and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness

And Wilderness is Paradise enow.

A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse, and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness

And Wilderness is Paradise enow.

—Edward FitzGerald

Whereas the British and American temperance movements had marched hand in hand during the first half of the nineteenth century, exchanging ideas, sharing tracts, and lending each other their orators, by the 1870s, when American women were invading saloons and American men were electing a dry president, their paths had diverged and the British temperance movement was in retreat. Although on paper its armies were intact, it had lost the fight for the hearts and minds of Britons to the nation’s brewers. Its defeat may be attributed in part to its reliance upon child soldiers, whom it had deployed in so-called

Bands of Hope

. The first Band of Hope, a temperance society dedicated to recruiting minors to the cause, was founded in Leeds in 1847 and within two years had “pledged 4,000 children between the ages of 6 & 16.” It was imitated the length and breadth of the land, and by 1860 there were 120 Bands of Hope in London alone, and several hundred thousand British children had committed themselves, or had been pledged by their parents, to a lifetime of total abstinence. Their faith in temperance was sustained throughout infancy and adolescence with propaganda and group outings. They were taught temperance songs and read temperate fairy tales, which had been revised to admit a bestiary of drunks and inebriated ogres. George Cruikshank, who illustrated many of the works of his friend Charles Dickens, was among the revisionists.

52

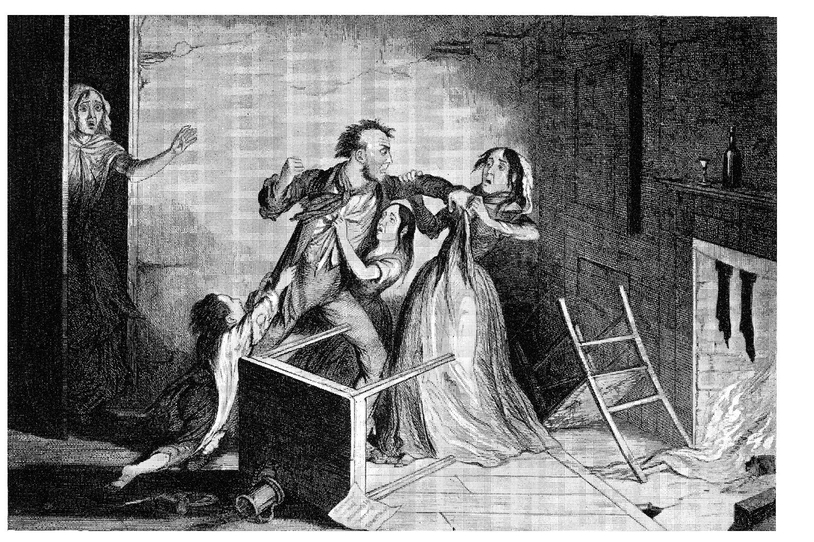

He had taken to abstinence with the fanaticism of a convert and expressed his new convictions through his art. Cruikshank dedicated two years of his life to a single giant allegorical painting, the

Triumph of Bacchus

. This shocking canvas, containing several hundred figures, has a monumental statue of the Greek deity of the title as its focus, raising a goblet of liquid perdition atop a pyramid of wine casks, from which issue fountains of the same fluid, which are distributed to the crowds at its base and thence throughout the rest of the canvas, to the general ruin of society. Fearful, perhaps, that he had not made the message clear, Cruikshank followed up with a series of engravings entitled

The Bottle

, which depicted the step-by-step ruin of a respectable family through the drunkenness of its breadwinner.

Bands of Hope

. The first Band of Hope, a temperance society dedicated to recruiting minors to the cause, was founded in Leeds in 1847 and within two years had “pledged 4,000 children between the ages of 6 & 16.” It was imitated the length and breadth of the land, and by 1860 there were 120 Bands of Hope in London alone, and several hundred thousand British children had committed themselves, or had been pledged by their parents, to a lifetime of total abstinence. Their faith in temperance was sustained throughout infancy and adolescence with propaganda and group outings. They were taught temperance songs and read temperate fairy tales, which had been revised to admit a bestiary of drunks and inebriated ogres. George Cruikshank, who illustrated many of the works of his friend Charles Dickens, was among the revisionists.

52

He had taken to abstinence with the fanaticism of a convert and expressed his new convictions through his art. Cruikshank dedicated two years of his life to a single giant allegorical painting, the

Triumph of Bacchus

. This shocking canvas, containing several hundred figures, has a monumental statue of the Greek deity of the title as its focus, raising a goblet of liquid perdition atop a pyramid of wine casks, from which issue fountains of the same fluid, which are distributed to the crowds at its base and thence throughout the rest of the canvas, to the general ruin of society. Fearful, perhaps, that he had not made the message clear, Cruikshank followed up with a series of engravings entitled

The Bottle

, which depicted the step-by-step ruin of a respectable family through the drunkenness of its breadwinner.

Despite mobilizing the children of the nation and issuing lurid propaganda, the British temperance movement failed to convert its aspirations into laws. Its lack of success was not for want of trying. Enthused by the triumph of their American cousins in Maine, the plethora of British temperance and abstinence societies had paused in their turf wars to throw their support behind the United Kingdom Alliance (UKA), which was founded in 1853 “to outlaw all trading in intoxicating drinks” and to create thereby “a progressive civilization” in Britain. The UKA spent the first four years of its life perfecting its publicity; then, in 1857, it turned to action. A bill was presented by a tame MP to the House of Commons that sought to limit the sale of alcohol via a so-called

Permissive Act

. Despite the promise of its name, the proposed act was anything but liberal. Its aim was creeping Prohibition—if enacted, a two-thirds majority of voters in an area would be empowered to ban drink shops within their locality. Critics outside the temperance movement pointed out that since the franchise was limited to adult males who owned property, a Permissive Act would enable 2/15ths of the population to “dictate to the remaining 13/15ths.” It also received fire from its own side. Teetotalers thought it did not go nearly far enough and resented the fact that it had been drafted by a brewer. In the event it got nowhere, and no farther when it was reintroduced in 1858, and every subsequent year until 1872, by which time its presentation had become a curious annual exercise in futility.

Permissive Act

. Despite the promise of its name, the proposed act was anything but liberal. Its aim was creeping Prohibition—if enacted, a two-thirds majority of voters in an area would be empowered to ban drink shops within their locality. Critics outside the temperance movement pointed out that since the franchise was limited to adult males who owned property, a Permissive Act would enable 2/15ths of the population to “dictate to the remaining 13/15ths.” It also received fire from its own side. Teetotalers thought it did not go nearly far enough and resented the fact that it had been drafted by a brewer. In the event it got nowhere, and no farther when it was reintroduced in 1858, and every subsequent year until 1872, by which time its presentation had become a curious annual exercise in futility.

Cruikshank’s

The Bottle

The Bottle

While the UKA was engrossed with its Permissive Act, and its constituents were busy recruiting hordes of children, British wine merchants were prospering with the encouragement of queen and country. In 1860, after fortifying himself with “a great stock of egg and wine,” Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone delivered his budget speech, in which he announced a cut in duty on French wines. Britons responded favorably to this largesse and, by 1866, had doubled their consumption and revived the economy of Bordeaux, which was going through a rough patch, at the same time. The 1860s and ’70s were also a golden age for brewing. British beer had never been better or more popular. Production raced to keep pace with demand. Between 1859 and 1876 annual per capita consumption rose from 23.9 to 34.4 gallons—about three times as much as was drunk by the average American. The statistics for spirit drinking were similarly encouraging. While they lagged their eighteenth-century ancestors and contemporary Americans by some distance, by 1875 the average Briton had rebuilt his or her average intake to 1.3 gallons of liquor per annum.

In retrospect, data showing that consumption of alcohol and membership in temperance societies were both trending in the same direction should have awakened the suspicions of each side, for they either implied that fewer people were drinking more or that many people who had pledged themselves to abstinence still drank. The truth was put to the test in 1872, when, in addition to the ritual submission of a Permissive Bill to Parliament, a Licensing Act intended to reform both the drinking laws and drinking habits of Great Britain was also introduced.

It was an emotive area of legislation, which demanded the modification of some of the oldest statutes in English law still in use, which, since their earliest forms, had protected the rights of access of the common man to good ale at a reasonable price and his freedom to consume it at his leisure. The nonvoting majority of the British public were notoriously sensitive to political tinkering with the licensing laws, and rioted if they thought that their rights to drink were likely to be abridged. Their point of view was shared even by temperance advocates such as Bishop Magee, who expressed his unease with the concept that Queen Victoria’s government should dictate the drinking habits of her subjects: “If I must take my choice . . . whether England should be free or sober, I declare—strange as such a declaration may sound, coming from one of my profession—that I should say it would be better that England should be free rather than that England should be compulsorily sober. I would distinctly prefer freedom to sobriety, because with freedom we might in the end attain sobriety; but in the other alternative we should eventually lose both freedom and sobriety.”

The debate over the merits of the 1872 Licensing Bill was extended by the beer, wine, and spirits interests, who accused its sponsors of being inspired by French radicalism. Liberal commentators further muddied the waters by suggesting that the bill was a Tory Trojan horse with capitalism hidden in its belly. Seduced by the alleged social benefits of temperance, Parliament might overlook the social problems caused by long hours, poor working conditions, wretched accommodation, and the absence of any fulfilling leisure activities other than drinking, and so mistake a symptom for the disease. Abstinent capitalists were the real enemies of British society, not the alcohol that the oppressed multitudes drank for solace.

Finally, nonconformists became entangled in the debate. Joseph Livesey, the original malt lecturer, accused evangelicals of hijacking his movement, claiming that teetotalism had become “a useful expedient only, for the furtherance of denominational religion.” Radical Protestant theologians, meanwhile, locked horns in a side quarrel as to the literal truth of the Bible, and indeed its relevance to the age of steam. Instead of trying to prove that the Old and New Testaments meant grape juice when they said wine, some extremists acknowledged their potency and held it out as evidence that the Good Book was nonsense on stilts and that its failure “to censure Noah for his drunkenness” was “only one of the numerous instances” of its “imperfect and perverted morality.”

The net result of so many conflicting interests was paralysis. The difficulty of trying to accommodate them all was summed up later by Lord George Cavendish: “If an angel from heaven were to come down and bring in a Licensing Bill, he would find it too much for him.” A Licensing Act of sorts was passed in 1872, which took, among others, the important steps of prohibiting the sale of ardent spirits to children under the age of sixteen

53

and clarifying statutory opening times for public houses. The act was roundly criticized by all parties and anathematized by temperance organizations. Keeping fifteen-year-olds away from gin was no great legislative leap forward toward a dry Britain. A single statistic explains best why their hopes were doomed to slaughter, with or without angelic assistance: In 1870, exactly a third of all British national tax revenues derived from the manufacture and sale of alcoholic drinks. Abstinence would bankrupt the nation. British brewers, distillers, and wine merchants made this important fact very clear to voters when they treated them in pubs during the 1874 election season. Gladstone, who lost, attributed his defeat to the power of the British drink industry and complained, “We have been borne down on a torrent of gin and beer.”

53

and clarifying statutory opening times for public houses. The act was roundly criticized by all parties and anathematized by temperance organizations. Keeping fifteen-year-olds away from gin was no great legislative leap forward toward a dry Britain. A single statistic explains best why their hopes were doomed to slaughter, with or without angelic assistance: In 1870, exactly a third of all British national tax revenues derived from the manufacture and sale of alcoholic drinks. Abstinence would bankrupt the nation. British brewers, distillers, and wine merchants made this important fact very clear to voters when they treated them in pubs during the 1874 election season. Gladstone, who lost, attributed his defeat to the power of the British drink industry and complained, “We have been borne down on a torrent of gin and beer.”

The death of temperance as a political cause in Great Britain was accompanied by an intellectual backlash against institutionalized sobriety. This process had commenced in 1859, when Edward FitzGerald’s

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

introduced the Arab

khamriyya

form of poetry to English literature. The

Rubaiyat

was as much invention as translation—FitzGerald intended to produce a single coherent piece rather than to revive the ad hoc structure of Omar Khayyam’s work. He was, however, careful to preserve the defiant tone of the original, with its emphasis on enlightenment through drinking rather than via philosophy or religion. The Christian audience whom FitzGerald addressed were challenged to consider the poem in the light of their own beliefs, rather than to dismiss it as Muslim fulminations against the limitations of Islam. As such, it was strong stuff—a frontal attack on the Christian doctrine of the resurrection of the body, which was then enjoying a surprising vogue, and indeed, on belief in an afterlife at all, whether corporeal, spiritual, or a combination of the two:

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

introduced the Arab

khamriyya

form of poetry to English literature. The

Rubaiyat

was as much invention as translation—FitzGerald intended to produce a single coherent piece rather than to revive the ad hoc structure of Omar Khayyam’s work. He was, however, careful to preserve the defiant tone of the original, with its emphasis on enlightenment through drinking rather than via philosophy or religion. The Christian audience whom FitzGerald addressed were challenged to consider the poem in the light of their own beliefs, rather than to dismiss it as Muslim fulminations against the limitations of Islam. As such, it was strong stuff—a frontal attack on the Christian doctrine of the resurrection of the body, which was then enjoying a surprising vogue, and indeed, on belief in an afterlife at all, whether corporeal, spiritual, or a combination of the two:

Ah, fill the Cup:—what boots it to repeat

How Time is slipping underneath our Feet:

Unborn TOMORROW, and dead YESTERDAY,

Why fret about them if TODAY be sweet!

One moment in Annihilation’s Waste,

One Moment, of the Well of Life to taste—

The Stars are setting and the Caravan

Starts for the Dawn of Nothing—Oh, make haste!

How Time is slipping underneath our Feet:

Unborn TOMORROW, and dead YESTERDAY,

Why fret about them if TODAY be sweet!

One moment in Annihilation’s Waste,

One Moment, of the Well of Life to taste—

The Stars are setting and the Caravan

Starts for the Dawn of Nothing—Oh, make haste!

The

Rubaiyat

was a commercial triumph and ran through five editions in FitzGerald’s lifetime. He altered the poem in successive texts, and some of the changes were made to emphasize that the wine it referred to was real wine, not a metaphor for divine inspiration, as had been suggested by hopeful temperates, and as such was proof that God connived at drinking:

Rubaiyat

was a commercial triumph and ran through five editions in FitzGerald’s lifetime. He altered the poem in successive texts, and some of the changes were made to emphasize that the wine it referred to was real wine, not a metaphor for divine inspiration, as had been suggested by hopeful temperates, and as such was proof that God connived at drinking:

Why, be this Juice the growth of God, who dare

Blaspheme the twisted tendrils as a snare?

A Blessing, we should use it, should we not?

And if a Curse—why, then, who set it there?

Blaspheme the twisted tendrils as a snare?

A Blessing, we should use it, should we not?

And if a Curse—why, then, who set it there?

However, while British politics, philosophy, and literature were turning against temperance, medicine gave it some welcome support. In 1860, French scientists had proved that the perceived warming qualities of alcohol were illusory, and thus killed off the so-called “heroic cures” that prescribed heroic amounts of alcohol to victims of “cooling” diseases like dysentery.

54

The mechanics of cirrhosis of the liver were explored and documented, experiments were carried out on animals, with sobering results: Alcohol, in the right doses, was a killer. No wonder the faces of gin drinkers, who still were common in mid-Victorian Britain, were “apoplectic and swollen, the scarlet color so dense that it is almost black; eyes dead, bloodshot, like those of a raw lobster.”

54

The mechanics of cirrhosis of the liver were explored and documented, experiments were carried out on animals, with sobering results: Alcohol, in the right doses, was a killer. No wonder the faces of gin drinkers, who still were common in mid-Victorian Britain, were “apoplectic and swollen, the scarlet color so dense that it is almost black; eyes dead, bloodshot, like those of a raw lobster.”

Other books

Headache Help by Lawrence Robbins

Snow White Sorrow by Cameron Jace

Better Left Buried by Emma Haughton

The Prince and I: A Romantic Mystery (The Royal Biography Cozy Mystery Series Book 1) by Julie Sarff, The Hope Diamond, The Heir to Villa Buschi

His Royal Prize by Katherine Garbera

The Garden of Eden by Hunter, L.L.

El castillo de Llyr by Lloyd Alexander

Her Viking Valentine (All Fired Up) by Kristen Painter

Secrets and Lies: He's a Bad Boy\He's Just a Cowboy by Lisa Jackson

Love Story by Jennifer Echols