Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (10 page)

| Pope | Pope |

| Archbishops | Masters of Orders |

| Bishops | Abbotts and Prioresses |

| Priests | Monks and Nuns, Canons and Friars |

| Laity |

The pope was held by Catholics to be the vicar of Christ and he and his subordinates to be earthly channels of God’s will. The problem with these hierarchies should be obvious: if the pope was the vicar of Christ and the king was God’s lieutenanton earth, who was higher in the Chain? What if they disagreed? Where did archbishops and bishops, abbots and – even worse –

female

prioresses fit amongst nobles and gentry? In practice, kings and popes generally cooperated with each other and, so, sustained the Chain. But when they disagreed, the repercussions were enormous. In previous centuries, the pope and the king of England had clashed over the respective jurisdictions of royal and ecclesiastical courts, over the collection of annates, and over which of them could select bishops (a struggle across Europe, known as the Investiture Controversy). Though the papacy had won some important concessions in these controversies, its prestige had taken a dramatic plunge in the fourteenth century. This happened, first, when the papal court moved in 1309 to Avignon in France, an event known as the Babylonian Captivity, which lasted until 1377. Most of the English ruling elite viewed the Avignon papacy as a mere tool of the French monarchy. Things only got worse between 1378 and 1417 when two popes, one Italian and one French, reigned in competition with each other during what came to be known as the Great Schism. The English Crown responded by approving legislation limiting the power of the pope to name clergymen to English benefices (the Statutes of Provisors, 1351, 1390), forbidding English subjects from appealing their cases to foreign courts, including the papal court at Rome, and blocking bulls of excommunication from entering England (

Statutes of Praemunire

, 1353, 1365, 1393). At about the same time, English kings also encouraged the questioning of papal authority by tolerating the existence of a group of heterodox Catholics called the

Lollards

. It was little wonder that at the beginning of the fifteenth century Pope Martin V (1368–1431; reigned 1417–31) commented: “it is not the pope but the king of England who governs the church in his dominions.”

13

Still, the Church remained a powerful and wealthy organization in late medieval England, with thousands of parishes and clergy, its own system of courts and access to the ears, minds, and, it was assumed, souls of every man, woman, and child in the realm. But the possibility always remained that royal authority and clerical authority might once more come into conflict. The resultant religious tensions will be another major theme of this book.

But in 1485 the most immediate challenge to the certainties of the Great Chain of Being came from the political arena. If papal authority could be questioned, so could royal authority. As this book opens, the English monarchy had just experienced the worst nightmare imaginable to those who embraced the Chain: a civil war in which the very person and authority of God’s lieutenant, the king, was up for contention. It is now necessary to examine this challenge to the Great Chain of Being; and the achievement of Henry VII (reigned 1485–1509), his supporters, and successors in meeting it.

CHAPTER ONE

Establishing the Henrician Regime, 1485–1525

On August 22, 1485 rebel forces led by Henry Tudor, earl of Richmond (1457–1509), defeated a royal army under King Richard III (1452–85; reigned 1483–5) at the battle of Bosworth Field, Leicestershire (see

map 4

). As all students of Shakespeare know, Richard was killed. His crown, said to have rolled under a hawthorn bush, was retrieved and offered to his opponent, who wasted no time in proclaiming himself King Henry VII. According to tradition, these dramatic events ended decades of political instability and established the Tudor dynasty, which would rule England effectively for over a century.

As told in Shakespeare’s

Tragedy of King Richard III,

Henry’s victory and the rise of the Tudors has an air of inevitability. But Shakespeare wrote a century after these events, during the reign of Henry’s granddaughter, Queen Elizabeth (1533–1603; reigned 1558–1603). Naturally, his hindsight was 20/20 and calculated to flatter the ruling house under which he lived. No one alive in 1485, not even Henry, could have felt so certain about his family’s prospects. During the previous hundred years three different royal houses had ruled England. Each had claimed a disputed succession and each had fallen with the murder of its king and head. Each line had descendants still living in 1485, some of whom had better claims to the throne than Henry did. Recent history suggested that each of these rival claimants would find support among the nobility, so why should anyone bet on the Tudors? In short, there was little reason to think that the bloodshed and turbulence were over.

And yet, though he would face many challenges, Henry VII would not be overthrown. Instead, he would rule England for nearly 25 years and die in his bed, safe in the knowledge that his son, also named Henry, would succeed to a more or less united, loyal, and peaceful realm supported by a full treasury. The story of how Henry VII met these challenges and established his dynasty will be told in this chapter. But first, in order to understand the magnitude of the task and its accomplishment, it is necessary to review briefly the dynastic crisis known, romantically but inaccurately, as the Wars of the Roses.

1

Map 4

The Wars of the Roses, 1455–85.

The Wars of the Roses, 1455–85

It might be argued that all of the trouble began over a century earlier because of a simple biological fact: King Edward III (1312–77; reigned 1327–77) had six sons (see genealogy 1, p. 429). Royal heirs were normally a cause for celebration in medieval England, but so many heirs implied an army of grandchildren and later descendants– each of whom would possess royal blood and, therefore, a claim to the throne. Still, this might not have mattered if two of those grandchildren, an earlier Richard and an earlier Henry, had not clashed over royal policy. Dominated by his royal uncles as a child, King Richard II (1367–1400; reigned 1377–99) had a stormy relationship with the nobility, especially his uncles’ children, as an adult. The most prominent critic was Henry Bolingbroke, duke of Lancaster (1366–1413), son of the John of Gaunt (1340–99) whom we met in the Introduction (see genealogy 1). In 1399 Richard confiscated Lancaster’s ancestral lands. Lancaster, aided by a number of other disgruntled noble families, rebelled against his cousin and anointed king, deposed him, and assumed the Crown as King Henry IV (1399–1413). In so doing, he established the Lancastrian dynasty on the English throne – but broke the Great Chain of Being. Looking back with hindsight, Shakespeare and many of his contemporaries thought that this was the moment that set England on the course – or curse – of political instability. In

The Tragedy of King Richard II,

he has the bishop of Carlisle predict the consequences of Henry Bolingbroke’s usurpation as follows:

And if you crown him, let me prophesy,

The blood of English shall manure the ground,

And future ages groan for this foul act …;

O if you raise this house against this house,

It will the woefullest division prove

That ever fell upon this cursed earth.

Prevent it, resist it, let it not be so,

Lest child, child’s children, cry against you – woe! (

Richard II

4.1)

Shakespeare, writing long after these events, knew that the prediction would come true. The speech is therefore not so much an accurate exposition of contemporary opinion at the time of Richard’s overthrow as it is a reflection of how English men and women came to feel about that event under the Tudors.

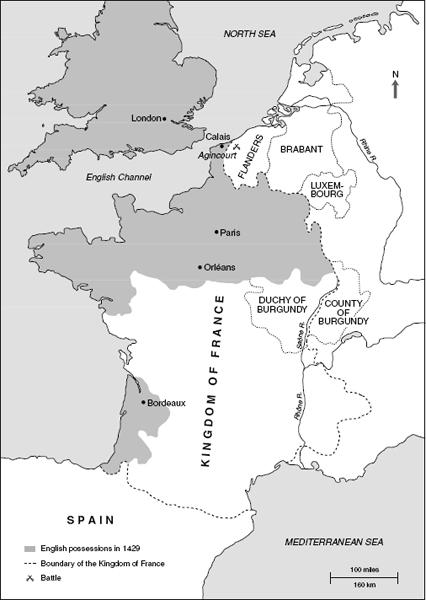

But many modern historians would point out that, despite his dubious rise to the top, Henry IV was a remarkably successful king. He established himself and his line, suppressing nearly all opposition by the middle of his reign. His son, Henry V (1386/7–1422; reigned 1413–22), did even better. He fulfilled contemporary expectations of kingship, revived the glories of Edward III’s reign, and distracted his barons away from any doubts they might have had about his legitimacy by renewing a longstanding conflict with France known as the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453). After winning a stunning victory over a much larger French force at Agincourt in 1415 (see

map 5

), Henry was recognized by the French king, Charles VI (1368–1422; reigned 1380–1422) as the heir to the French throne as well. This, despite the fact that Charles had a son, also named Charles (1403–61). In fact, central and southern France remained loyal to the

dauphin

(the French crown prince), provoking Henry into another campaign in 1421–2. It was on his way to besiege a recalcitrant French city, that Henry V contracted dysentery and died.

Map 5

Southern England and western France during the later Middle Ages

The untimely death of Henry V was, for many historians, the real starting point for the disasters to come, for, combined with the almost simultaneous demise of Charles VI, it brought to the English and French thrones an infant of just nine months: Henry VI (1421–71; reigned 1422–61, 1470–1). Given his youth, it was inevitable that the early years of the new king’s reign would be dominated by the nobility, in particular his many royal relatives. But even after being declared of age in 1437, he proved to be a meek, pious, well-intentioned but weak-minded nonentity. Eventually, he went insane. Even before he did so, he was dominated by family and courtiers, in particular his great-uncles of the Beaufort family, dukes of Somerset; and from 1444 his wife, Margaret of Anjou (1430–82). They became notorious for aggrandizing power and wealth, for running a corrupt and incompetent administration, and for losing France. In 1436, Paris fell back into French hands. By 1450 the French had driven the English out of Normandy. By 1453, what had once been an English continental empire had been reduced to the solitary Channel port of Calais (

map 5

). The French had won the Hundred Years’ War. The loser was to be Henry VI and the house of Lancaster.

Put another way, the end of the Hundred Years’ War is important in French history because it produced a unified France under a single acknowledged native king. It is important in English history because it destabilized the English monarchy and economy, discredited the house of Lancaster, and divided the English nobility. The result was the Wars of the Roses. Remember that the Lancastrians had come to the Crown not through lawful descent, but through force of arms. Now their military skills had proved inadequate. Moreover, the wars against France had been very expensive and ruinous to trade. In 1450 the Crown’s debts stood at £372,000; its income but £36,000 a year, a steep decline from an annual revenue of £120,000 under Richard II. The House of Commons refused to increase taxes, knowing that they would go either to a losing war effort or to line Beaufort pockets. Since royal revenue was not keeping up with expenditure, the king could only pay for military affairs by borrowing large sums at exorbitant rates of interest. Worse, in the spring of 1450 a popular rebellion, led by an obscure figure named Jack Cade (d. 1450), broke out in the southeast. The rebels justified their actions with a sweeping indictment of Henry VI’s reign: “[His] law is lost, his merchandise is lost; his commons are destroyed. The sea is lost; France is lost; himself is made so poor that he may not pay for his meat or drink; he oweth more and [is] greater in debt than ever was King in England.”

2

Cade was killed and his rebellion suppressed with some difficulty, but the problems of royal control, finance, and foreign policy would overwhelm the Lancastrian regime.